Sonic the Hedgehog (2020)

*/****

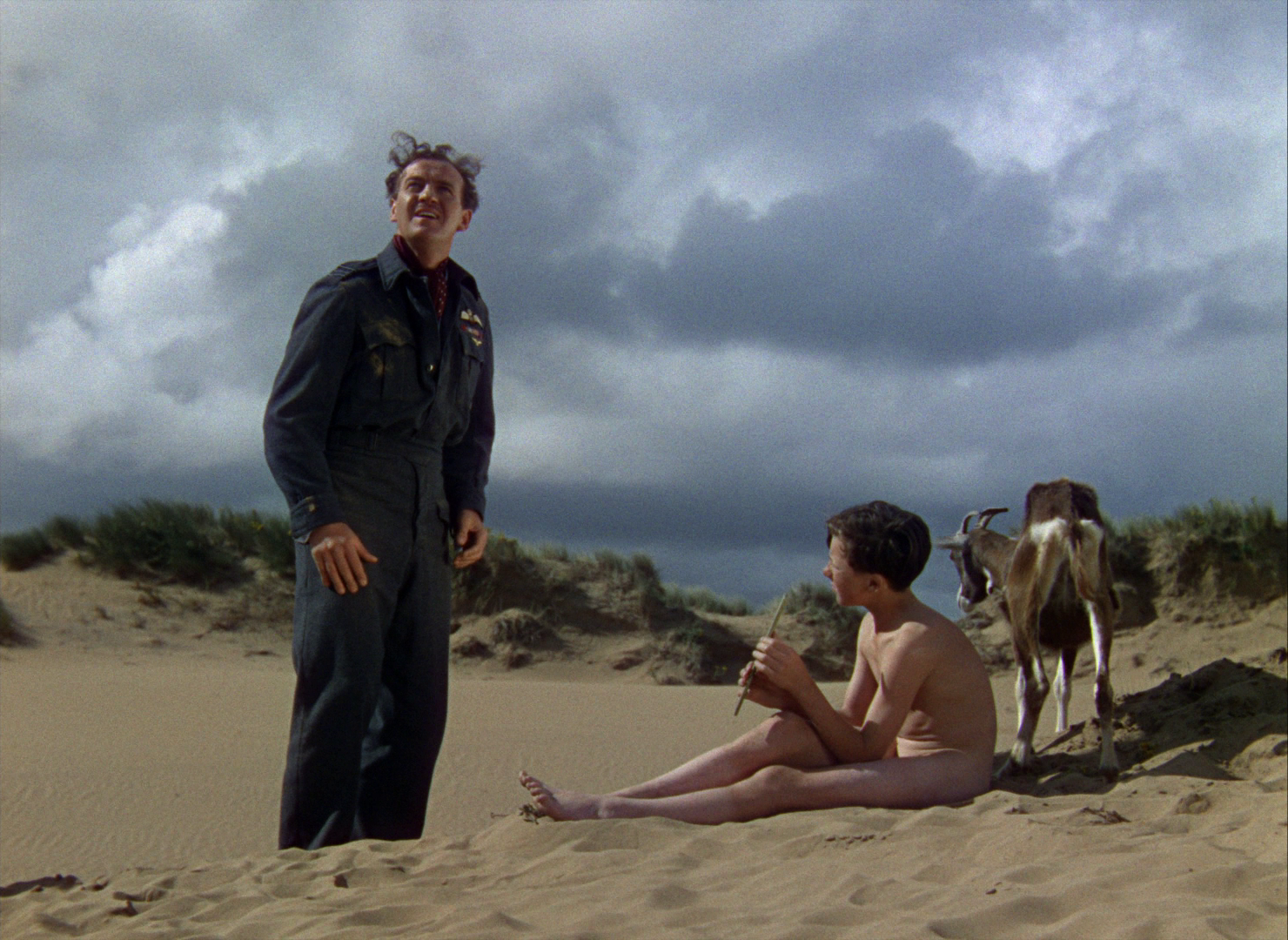

starring James Marsden, Ben Schwartz, Tika Sumpter, Jim Carrey

written by Pat Casey & Josh Miller

directed by Jeff Fowler

by Walter Chaw At some point, Jeff Fowler’s Sonic the Hedgehog, based on the tentpole for the Sega Genesis video-game system, achieves a certain queasy, weightless critical mass of pomo fascination. The story elements, the graphics-I-mean-art-direction, the affable James Marsden boyfriend archetype and manic Jim Carrey capering–all of these elements are so familiar they’re almost subliminal, mashed together in epileptic flashes to tell an also intrinsically familiar story about a journey across the country with an alien buddy. Starman, Paul, E.T.–just the first references to register (and as soon as they register, make way for the next set). Sonic the Hedgehog is very much like encountering a Frankenstein’s monster constructed out of The Beatles. Oh god, oh Christ, I recognize this, I know from whence this abomination sprang. It is the well of our culture gone rank. The picture’s closest analogue isn’t other video-game movies, it’s Spielberg’s knowingly self-loathing Ready Player One, which doesn’t get the credit it should for being ashamed of itself. You might feel like Sonic the Hedgehog is “good,” but that’s you mistaking “good” for “Oh, I know all the words to this song at karaoke, it’s good!” Not necessarily.