Occupied City (2023)

***/****

based on the book by Bianca Stigter

directed by Steve McQueen

Now playing in Toronto at TIFF Bell Lightbox.

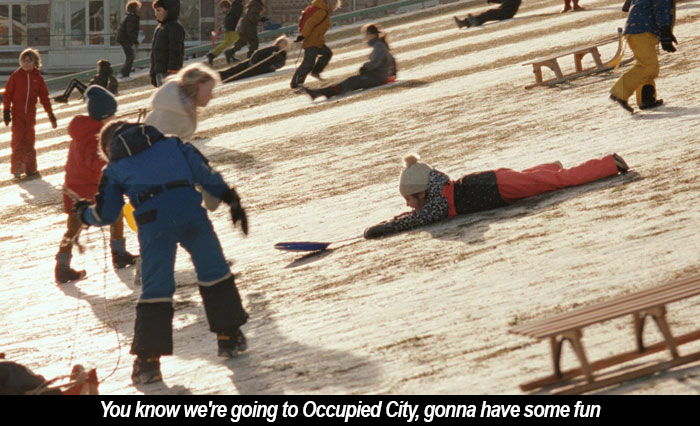

by Angelo Muredda Late in Steve McQueen’s Occupied City, the filmmaker’s elliptical, 4.5-hour nonfiction adaptation of co-screenwriter and partner Bianca Stigter’s book Atlas of an Occupied City: Amsterdam 1940-1945, a speaker at a commemoration for the victims of the Atlantic slave trade looks out into the audience at the Oosterpark and asks, “How do we create room for each other?” The site of that event, disembodied narrator Melanie Hyams tells us, was the storage yard for the occupying Nazi army’s vehicle fleet in the later days of the war, with German soldiers shooting at anyone who dared to steal stockpiled wooden blocks for use in their stoves. McQueen’s project in adapting such a sprawling, non-narrative text about the city he sometimes lives in is similarly anchored in the work of making room–not just for the myriad kinds of people who have lived and died there in the past 80 years, especially during the Second World War, but for the past and present as well.