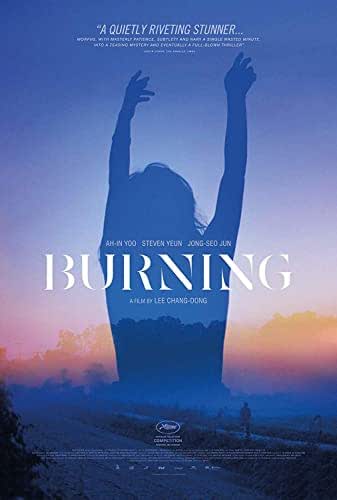

****/**** Image A Sound A Extras D

starring Ah-in Yoo, Steven Yeun, Jong-seo Jun

screenplay by Oh Jung-mi & Lee Chang-dong, based on the short story “Barn Burning” by Haruki Murakami

directed by Lee Chang-dong

by Walter Chaw When she was seven, she fell into a dry well and spent a day there, crying up into the round sky until he found her. She’s Haemi (Jong-seo Jun), maybe 20 now, working as a live model with a bare midriff, standing on a busy street, dancing next to a prize-wheel and giving out “tacky” things to, predominantly, men buying raffle tickets from the pretty girl. He is Jongsu (Ah-in Yoo), of the perpetually slack expression. He doesn’t remember the well, nor rescuing her from it, nor the day he stopped her in the street on the way home from junior high to tell her she was ugly. “It’s the only thing you ever said to me,” she remembers. “I had plastic surgery. Pretty, right?” she asks him, but it’s rhetorical. They fuck in an awkward, desultory way, with him looking at how the sunlight bounces off a tower in downtown Seoul, into her tiny apartment. (She’s told him he’d be lucky to see it.) He goes back there to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, and masturbates absently to the afterimage of her picture as he stares out the window. When she returns from her trip, it’s on the arm of sexy, urbane Ben (Stephen Yeun). Ben likes Haemi because she cries–he doesn’t–and can fall asleep whenever and wherever. He enjoys her guilelessness. “What’s a metaphor?” Haemi asks Ben. Ben smiles in his empty way and tells her to ask Jongsu. Jongsu is, after all, an aspiring writer. “[Ben]’s the Great Gatsby,” Jongsu tells Haemi–young, wealthy, and mysterious. Jay Gatsby is a metaphor. Jongsu says that Korea is full of Gatsbys.

by Walter Chaw When she was seven, she fell into a dry well and spent a day there, crying up into the round sky until he found her. She’s Haemi (Jong-seo Jun), maybe 20 now, working as a live model with a bare midriff, standing on a busy street, dancing next to a prize-wheel and giving out “tacky” things to, predominantly, men buying raffle tickets from the pretty girl. He is Jongsu (Ah-in Yoo), of the perpetually slack expression. He doesn’t remember the well, nor rescuing her from it, nor the day he stopped her in the street on the way home from junior high to tell her she was ugly. “It’s the only thing you ever said to me,” she remembers. “I had plastic surgery. Pretty, right?” she asks him, but it’s rhetorical. They fuck in an awkward, desultory way, with him looking at how the sunlight bounces off a tower in downtown Seoul, into her tiny apartment. (She’s told him he’d be lucky to see it.) He goes back there to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, and masturbates absently to the afterimage of her picture as he stares out the window. When she returns from her trip, it’s on the arm of sexy, urbane Ben (Stephen Yeun). Ben likes Haemi because she cries–he doesn’t–and can fall asleep whenever and wherever. He enjoys her guilelessness. “What’s a metaphor?” Haemi asks Ben. Ben smiles in his empty way and tells her to ask Jongsu. Jongsu is, after all, an aspiring writer. “[Ben]’s the Great Gatsby,” Jongsu tells Haemi–young, wealthy, and mysterious. Jay Gatsby is a metaphor. Jongsu says that Korea is full of Gatsbys.

Lee Chang-dong’s Burning is an adaptation of a Haruki Murakami short story called “Barn Burning” in the way that Under the Skin is an adaptation of Michel Faber’s novel–or, closer to the bone, in the way that No Country For Old Men is an adaptation of not merely Cormac McCarthy’s book, but the whole of McCarthy’s oeuvre. It understands Murakami in a biological way. It shares his rhythms, the quiet expressionism, the way that cats are a metaphor for a household. Haemi calls her cat “Boil” because he was found in a boiler room. That’s a metaphor, too. Burning is an extraordinarily long burn. Its score, by the Korean film composer Mowg, is all quiet, noodling jazz–the evocation of Murakami’s penchant for referring to Miles Davis now and then in his work. In the short story, a scene where Ben, Jongsu, and Haemi have dinner at Ben’s is punctuated by Haemi picking a Miles Davis record from Ben’s collection to play on the turntable. This doesn’t happen in the film, but the music is there anyway, diaphanously, like a neighbour across the courtyard left her window open with “Kind of Blue” spinning quietly through its worn grooves. Maybe it’s more like how when that record you love is so worn you start to hear the ghosts of cuts on the flipside. Ben asks Jongsu who his favourite author is and Jongsu, in the Murakami fashion, mentions a Western writer, William Faulkner. Faulkner, as it happens, also has a short story called “Barn Burning.” In it, a child attends his father’s trial–a father who has rage in him and stands accused of setting a neighbour’s barn on fire. Ben sets abandoned greenhouses on fire. Jongsu’s father is on trial and about to go away for a long time because of the anger inside him. When Jongsu moves into his family’s old country home, he uncovers a lockbox filled with deadly knives. His face is a perfect “o,” all of quiet surprise and incomprehension.

Greenhouses figure large as a metaphor in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep. Murakami references The Big Sleep–the movie version–in his novel Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, but then cites the book repeatedly throughout in a series of buried, complex samplings. Chandler, in a line that made it to the screen, mentions Proust at a critical juncture, likening him to Marlowe because he gives the impression of someone who works from bed. (Chandler clarifies that Proust is a “connoisseur of degenerates.”) Murakami begins his novel with a similar allusion to Proust. Both works reference the recovery of lost time. Lee transforming the subject of Ben’s pyromaniacal attention from barns to greenhouses is deep fauna, in other words: an intellectually acrobatic deciphering of Murakami’s texts to reach this place where it looks, sounds, feels, indeed functions like Jongsu’s rhetorical confusion. Before Haemi leaves on her vision quest to Kenya, she introduces Jongsu to the idea of small hungers and big hungers. Small hungers are physical hungers; big hungers are existential ones. When she returns, she tells a gaggle of Gatsbys about her experience watching native Africans dance around a bonfire, starting with small gestures to express their small hungers and building to entreaties to the heavens in the hopes of redressing their big hungers. The group gets her to dance for them. You watch very closely for signs they’re mocking her. I think they are; or they would be if they cared. Ben says later that he’d do anything if it were fun. I don’t know that we share ideas of what’s fun with people from different social/financial classes. Maybe that’s what Burning‘s about. At the least, it’s one thing Burning‘s about.

Lee raises the spectre of Faulkner throughout Burning. There’s Jongsu’s admiration for the author, for one, and at one point Ben, inspired by Jongsu, is seen reading a collection of Faulkner’s short stories. I have that exact edition, in English of course, and the first story in it is “Barn Burning.” Ben tells Jongsu he would like to tell Jongsu his story one day. Jongsu, who doesn’t know what he should be writing about, is non-committal. He writes a petition to serve as a character defense for his father before his father’s sentencing, and one of the signers says that it’s beautifully written, even if the part about his father being “friendly” is a stretch. Later, we see Jongsu through a window in a familiar aspect, but where once he was blankly jerking off, now he’s writing something at last. I wonder if the implication isn’t that they’re essentially the same pursuit. In the Faulkner story, the son successfully gets the father off, but the family is exiled and, in the end, the father is killed, due in some part to his son’s betrayal, in the process of burning another barn. In Burning, Ben tells Jongsu that he’s set fire to a greenhouse very close to Jongsu’s family home, and that the reason Jongsu found no trace of it is because it can be hard to see things when they’re too close to you. If Ben isn’t a metaphor, he is at least the existential catalyst for Jongsu realizing that he, himself, is the metaphor. He is Nick Carraway: the observer, the chronicler, in love with an ideal and the only pallbearer when that ideal is destroyed. In the Murakami story, Jongsu says that Gatsby is a “riddle.” Better to ask not what is the answer to the riddle, but what is the nature of it. Burning is a riddle, too. It doesn’t really offer an answer. Haemi, visiting Jongsu’s place with Ben, takes off her shirt at twilight and dances her “big hunger” dance for no one. She cries. Before she leaves, Jongsu tells her that only whores are that comfortable with their bodies around men. He loves her and is cruel to her in the way that only people who love someone can be cruel to them.

Burning is about dread and the end of things. It sees characters at the beginning of their adult lives already scarred almost to death and rendered all but unrecognizable by their experience. It’s about looking for answers and finding them and forgetting what the questions were in the first place. It has a lot in common with George Sluizer’s Spoorloos and some in common with Douglas Adams’s writing. It is, like Murakami’s prose, dense with references to the modern Western canon. It is, like each of Lee’s films, literary and steeped in critical theory. Jongsu is Carraway and Faulkner’s Sartoris and Chandler’s Marlowe: the detective, the voyeur, the child. He loves Haemi better than Ben does, he thinks, but he can’t actually know that. We can’t either, we just like him more than we like Ben because Ben seems the sort of rich creep who lacks empathy because he shares no experiences with ordinary people. He’s smooth and frictionless, like the river rock he spirits into Haemi’s hand as a gag and as a metaphor for the stone in Haemi’s heart preventing her from telling men she likes that she likes them. She looks at Jongsu when Ben tells her this, and we read a lot into it because we’re on the Jongsu train. But should we? Then Haemi vanishes and no one knows where she’s gone. Her apartment is empty, her cat is missing, the landlady insists there never was a cat. All warmth has fled. When Jongsu starts a fire at the end, well, maybe he’s trying to create some warmth. Maybe he’s just trying to get warm. I don’t know what the question was. Burning is a masterpiece because it’s about Kierkegaardian fear and trembling and it comes to the same conclusions. There are no answers for you, only the feeling of dread. And the duty of love, if you’re lucky enough to embrace it. There’s always that. Originally published: November 3, 2018.

THE BLU-RAY DISCby Bill Chambers Well Go USA shepherds Burning to Blu-ray in an impeccable 2.40:1, 1080p transfer. Some banding on the introductory Well Go logo made me nervous, but I think it might be baked into the file they pull whenever they use it, because I’ve spotted it on other releases as well. And because compression artifacts are not an issue during the movie proper, whose bitrate averages a more than generous 35 Mbps. The picture was shot with the ARRI Alexa XT Plus and has the crisp, clean look of today’s high-end digital filmmaking. Be that as it may, it looks plenty cinematic in motion and still would even without what appears to be a scrim of artificial grain. (As it’s consistent under various lighting conditions, I don’t think it’s camera noise.) The image maintains an elegant naturalism but bursts with colour when called upon to do so, and though it can be dim at times, essential details such as the expression on Haemi’s face as she sways to the music in her head, silhouetted by the twilight sky, are never lost to shadow. Attending the video, a Korean 5.1 DTS-HD MA track features a robust centre channel and impressive spatial clarity, especially when it comes to Mowg’s Badalamenti-esque score. A scene where the characters go dancing at the one-hour mark pummels the subwoofer with that insistent, clubby bass, bringing the default reservedness of the mix into stark relief. There’s only one extra directly related to the movie, the 2-minute “Burning: 140 Days of Passionate Performance,” which marries an aural montage of the three leads commenting on their characters to a compilation of B-roll and clips from the film. For what it’s worth, it’s subtitled even when Steven Yeun is speaking English, something I always appreciate since my brain refuses to instantly adapt to a switch in spoken language. That said, this doesn’t make up for the unsatisfying brevity of the piece. In addition to a teaser and two trailers for Burning, previews for the Korean Swing Kids, Shadow, and The Endless round out the disc. (The last three also cue up on startup.) A DVD copy of Burning is included with the Blu-ray.

148 minutes; R; 2.39:1 (1080p/MPEG-4); Korean 5.1 DTS-HD MA, Korean DD 2.0 (Stereo); English subtitles; BD-50 + DVD-9; Region A; Well Go USA