A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951)

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951)

****/**** Image A Sound A Extras A+

starring Vivien Leigh, Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, Karl Malden

screenplay by Tennessee Williams, based on his play

directed by Elia Kazan

BABY DOLL (1956)

****/**** Image B Sound A Extras B+

starring Karl Malden, Carroll Baker, Eli Wallach, Mildred Dunnock

screenplay by Tennessee Williams

directed by Elia Kazan

CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF (1958)

CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF (1958)

****/**** Image A Sound A Extras C

starring Elizabeth Taylor, Paul Newman, Burl Ives, Jack Carson

screenplay by Richard Brooks and James Poe, based on the play by Tennessee Williams

directed by Richard Brooks

THE ROMAN SPRING OF MRS. STONE (1961)

*/**** Image A Sound A Extras C

starring Vivien Leigh, Warren Beatty, Lotte Lenya, Jill St. John

screenplay by Gavin Lambert, based on the novel by Tennessee Williams

directed by José Quintero

SWEET BIRD OF YOUTH (1962)

***/**** Image B- Sound A- Extras A

starring Paul Newman, Geraldine Page, Shirley Knight, Ed Begley

screenplay by Richard Brooks, based on the play by Tennessee Williams

directed by Richard Brooks

THE NIGHT OF THE IGUANA (1964)

****/**** Image B- Sound B- Extras A

starring Richard Burton, Ava Gardner, Deborah Kerr, Sue Lyon

screenplay by Anthony Veiller and John Huston, based on the play by Tennessee Williams

directed by John Huston

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ SOUTH (1973)

**½*/**** Image C Sound D

directed by Harry Rasky

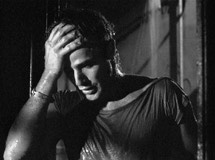

by Walter Chaw Marlon Brando is liquid sex in A Streetcar Named Desire, molten and mercurial. He’s said that he modeled his Stanley Kowalski after a gorilla, and the manner in which Stanley eats, wrist bent at an almost fey angle, picking at fruit and leftovers in the sweltering heat of Elia Kazan’s flophouse New Orleans, you can really see the primate in him. (Imagine a gorilla smelling a flower.) Brando’s Stanley is cunning, too: he sees through the careful artifice of his sister-in-law Blanche (Vivien Leigh, Old Hollywood), and every second he’s on screen, everything else wilts in the face of him. It’s said that Tennessee Williams used to buy front-row seats to his plays and then laugh like a loon at his rural atrocities; he’s something like the Shakespeare of sexual politics, the poet laureate of repression, and in his eyes, he’s only ever written comedies. In Kazan’s and Brando’s too, I’d hazard, as A Streetcar Named Desire elicits volumes of delighted laughter. The way that Stanley’s “acquaintances” are lined up in his mind to appraise the contents of Blanche’s suitcase. The way he invokes “Napoleonic Law” with beady-eyed fervour. And the way, finally, that he’s right about Blanche and all her hysterical machinations. The moment Stanley introduces himself to Blanche is of the shivers-causing variety (like the moment John Ford zooms up to John Wayne in Stagecoach), but my favourite parts of the film–aside from his torn-shirt “STELLA!”–are when Stanley screeches like a cat, and when he threatens violence on the jabbering Blanche by screaming, “Hey, why don’t you cut the re-bop!”

by Walter Chaw Marlon Brando is liquid sex in A Streetcar Named Desire, molten and mercurial. He’s said that he modeled his Stanley Kowalski after a gorilla, and the manner in which Stanley eats, wrist bent at an almost fey angle, picking at fruit and leftovers in the sweltering heat of Elia Kazan’s flophouse New Orleans, you can really see the primate in him. (Imagine a gorilla smelling a flower.) Brando’s Stanley is cunning, too: he sees through the careful artifice of his sister-in-law Blanche (Vivien Leigh, Old Hollywood), and every second he’s on screen, everything else wilts in the face of him. It’s said that Tennessee Williams used to buy front-row seats to his plays and then laugh like a loon at his rural atrocities; he’s something like the Shakespeare of sexual politics, the poet laureate of repression, and in his eyes, he’s only ever written comedies. In Kazan’s and Brando’s too, I’d hazard, as A Streetcar Named Desire elicits volumes of delighted laughter. The way that Stanley’s “acquaintances” are lined up in his mind to appraise the contents of Blanche’s suitcase. The way he invokes “Napoleonic Law” with beady-eyed fervour. And the way, finally, that he’s right about Blanche and all her hysterical machinations. The moment Stanley introduces himself to Blanche is of the shivers-causing variety (like the moment John Ford zooms up to John Wayne in Stagecoach), but my favourite parts of the film–aside from his torn-shirt “STELLA!”–are when Stanley screeches like a cat, and when he threatens violence on the jabbering Blanche by screaming, “Hey, why don’t you cut the re-bop!”

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951)

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) by Travis Mackenzie Hoover

by Travis Mackenzie Hoover