Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma

***½/**** Image A- Sound B+ Extras B+

starring Paolo Bonacelli, Giorgio Cataldi, Umberto P. Quintaville, Aldo Valletti

screenplay by Pupi Avati (uncredited) and Pier Paolo Pasolini

directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

by Bryant Frazer There’s a tradition among purveyors of BDSM pornography to append a coda to their project in which the participants in various potentially alarming scenarios are finally glimpsed, all smiles, revelling in the afterglow of a clearly consensual exercise. I assume this custom has very practical benefits–for one thing, it might help stave off prosecution for obscenity or sex-trafficking. But it’s also a signal from the community making the videos to the community watching them that the performances are undertaken with high spirits, lest there be any misunderstanding about the actual circumstances of their making. Despite any apparent unpleasantness, dear viewer, all involved (top and bottom, dominant and submissive) are working towards the ultimate goal of pleasure, not pain.

I was intrigued to learn that Pier Paolo Pasolini carefully planned and shot what might have been a similar dear-viewer addendum to his notoriously repellent screed Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (hereafter Salò), which appropriates the work of the Marquis de Sade as a means for understanding the social, political, and sexual pressures of the late 20th century. The film, populated by aging prostitutes in fabulous evening gowns, leering fascists in conformist business attire, peasant children of both sexes, and a single provider of musical accompaniment to the whole debacle on piano and accordion, is rife with scenes of physical and psychological degradation ranging from humiliation and coprophagia to outright rape and murder. Pasolini also shot a tag that depicted the film’s cast and crew (including the director himself) dancing on location. This would have appeared at the film’s beginning or at its very end, depending on whose account you favour, and it might have served to remind viewers of the passionate creative mind that drove what would become, with the director’s murder before the picture’s release, a surpassingly horrible final gesture on Pasolini’s part.

Watching Salò is an endurance test by any stretch. The film features enough liberally exposed skin, male and female, to qualify as broad-based titillation in a purely visual sense. Yet Pasolini’s scenario pushes back against ordinary sex appeal at every opportunity with violent depictions of unfettered sadism. You may start to wonder about the condition of these fresh-faced young actors made to crawl on all fours, leashed as dogs; to mime the experience of gagging on excrement; and to place themselves on display during the climactic torture tableaux, staked out in the dirt like gazelles at the waterhole. Where are they from? Are any of them professionals? Did they know what they were getting into? Were they scarred for life?

By some accounts, the mood on set was incongruously merry, but for whatever reason, Pasolini finally left the great Salò dance party on the cutting-room floor. It’s possible that, at some point during the editing, he decided to close that particular safety hatch–to abandon the cinematic equivalent of a safe word. It’s not that Pasolini was one of those directors who liked to use Bad Sex as a cudgel against audiences. (I’m looking at you, Bertolucci.) Pasolini’s latter career coincided with the rise of the sex film, and he had himself pushed at the envelope with the earthy and sexy Trilogy of Life that became his greatest commercial success: The Decameron (1971), Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1974).

Still, Pasolini, an outspoken critic of consumer culture and globalism, found reason to be cynical about sex on screen. He saw his own work co-opted and regurgitated by filmmakers who made dreary softcore knock-offs with similar titles. He was, no doubt, aware of the burgeoning market for hardcore films that sought to exploit human sexual encounters as an entertainment commodity. He may also have noted the first stirrings of the sadiconazista cycle of Nazi-themed sex movies (most famously exemplified by the notorious cheapie Ilsa: She-Wolf of the SS) that were about to enjoy a brief but intense period of popularity–at least he was cognizant that the intersection of fascism and sexuality, already probed on screen by fellow Italians Luchino Visconti (The Damned) and Liliana Cavani (The Night Porter), would find more crudely exploitative outlets soon enough.

The point is that while Salò may fit several definitions of pornography, it is more interesting as the opposite thing: anti-pornography. More specifically, it extends the idea of pornography to a breaking point. It is, in part, a reaction against pornography. (Pasolini even wrote an essay declaring an “abjuration” of his own previous trilogy, which he came to regard as hopelessly naive in its celebrations of beauty, purity, and innocence.) Salò should play like the ultimate exploitation movie, with its scenes of copious nudity, degradation, and general fiendishness, but exploitation fans often come away nonplussed. It has a dark spirit all its own that confounds voyeurism.

For one thing, Salò demands extra-textual interpretation. (The opening credits actually include a reading list! Off to the library with you, dear viewer.) The audience member needs to know a little something about the history of fascism in Western Europe, if not about Pasolini himself, in order to start making heads or tails of it. It helps to know that the title sets the film in the final days of Mussolini’s Italian Social Republic, a puppet state of Nazi Germany created in the north of Italy in 1943 with headquarters in the village of Salò. Tens of thousands were killed there or sent to concentration camps. Pasolini recasts the merciless libertines of Sade’s conception as pillars of Italian society (the Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate, and the President), identifying them as enablers and beneficiaries of fascist policy. Here, they’re seen relying on smirking, chortling soldiers–corrupted, one suspects, by the taste of power their masters have allowed them–to ride herd over a cohort of kidnapped teenagers who will be forced to participate in the debauchery pending their executions.

However, it’s only the movie’s opening minutes, which show boys and girls being rounded up from nearby villages, that resemble historical events. (One of the villages, where a runaway from the libertines’ convoy is gunned down as he attempts his escape, is Marzabotto, site of one of the worst massacres perpetrated by the Republic of Salò.) If not for the introductory title identifying these environs as the “Antechamber of Hell,” the film might play as an unexceptional wartime melodrama, sexed up a bit by the promise of nubile victims. Once the action moves indoors, the picture tumbles through the looking glass. The bulk of Salò takes place in one location, a heavily guarded country villa that invites at least three different interpretations. In the most literal interpretation, the film simply transposes a Sadean orgy to that many-roomed prison in northern Italy. The droning and booming noises that thrum away on the soundtrack represent the noise of World War II, its air raids and explosions, raging outside. Pasolini explicitly encourages a second reading that places Salò in Hell itself, with title cards welcoming viewers to the three Dantean circles of “Obsession,” “Shit,” and finally “Blood.” On an even more ghoulish level, the location unavoidably suggests a concentration camp lorded over by martinets who are confident that none of their prisoners will get out alive.

These rooms are impeccably photographed by Tonino Delli Colli, often in wide shots that emphasize the smallness and vulnerability of the actors while highlighting the relentless symmetry of the spaces they inhabit. (Watching Salò repeatedly, you start to notice how many elements are doubled on the human figure–breasts, buttocks, and balls.) The balanced compositions are amplified by odd pieces of set-dressing that add detail and interest to the shots–huge mirrors, obscenely bulbous or phallic chandeliers, and a bounty of modern artwork, much of it comprising pieces that were actually banned by the fascists. You might notice what’s not on display: any semblance of a swastika. That’s an indication of how Pasolini’s vision for the film expanded beyond high-concept fascist allegory.

We don’t have to wonder about Pasolini’s motives in making Salò; they are well documented. And while the fascists were clearly targets of opportunity, Pasolini insisted that the film’s social dimension did not stop in Italy circa 1945, but instead depicted the vile conditions engendered by what he called “the anarchy of power.” He believed, as the picture asserts, that fascists exerted their power by denying the humanity of others, but he extended the criticism to capitalism and industrial society in general. He famously defended the scenes of shit-eating as commentary on the processed-food industry–on the way that poor people learn to shovel down the heaping helpings of chemical-rich, nutrient-poor dinners sold cheaply in supermarkets. And the metaphor is so good, so perfect, that I think it gives even the film’s fiercest critics pause.

It does raise the question of whether a movie is any good if you have to read the director’s statement in order to understand what it’s up to, but there’s a lot going on here that won’t be apparent to a virgin viewer, whose senses will likely be reeling from the weirdly asexual depravity on screen. My first viewing of Salò was pretty unpleasant, and not just because it took place on the lousy DVD transfer that qualified as a Criterion release back in the late 1990s. I was sort of flabbergasted that something that looked, on paper, like a highbrow exercise in Eurocult eroticism was so hard to process as a sex film. I still don’t know how you undress more than a dozen young Italian actors and actresses on screen without turning anybody’s crank, but Pasolini figured it out. Probably it has something to do with unflattering lighting and camera angles, Pasolini’s refusal to indulge anything like an erotic “male gaze,” and the lurking presence of four devoutly creepy, perpetually turgid old men either in the frame or just outside of it.

On repeat viewings, after I had learned to stop worrying and at least make peace with the idea of Salò, it became easier to appreciate Pasolini’s technical strategies, his formal control, and even the sense of humour the film rarely gets credit for. Of special merit here is the remarkably disturbing physical performance by the redheaded Aldo Valetti, embodying the wisecracking President as a special kind of unspeakable pervert who helps reveal the movie’s black-comic notes. It’s Valetti who, during the aforementioned excrement feast, gets Salò‘s best line. “Carlo,” he says, addressing one of the blank-eyed boys at the table, “do this with your fingers”–and here he tugs his lips out into a grotesque smile–“and say, ‘I can’t eat rice with my fingers like this.'” Carlo obliges, ridiculously mumbling past his fingers and soft, stretched lips, “I can’t eat rice.” And the President barks back, “Then eat shit.” It’s a tremendous moment–the President is obviously hip to the let-them-eat-cake connotations of his line, and it cracks him up. Moreover, it turns him on. A few minutes earlier, one of the girls gags on her meal and pleads to a friend sitting across the table, “I can’t go on.” The dispirited response comes in an oddly matter-of-fact tone, with a veritable shrug of her teenage shoulders: “Offer it to the Madonna.” It’s funny because it’s such a wholly inadequate response to the horror show that is Salò. Abandon all hope, ye who enter.

The title card reading “Circle of Blood” gives way to an image of three of the Libertines made up in drag wearing ridiculous hats that made me think Terry Gilliam could be the man for a contemporary remake of Salò, perhaps staged as a grandiose opera à la his Damnation of Faust. Or Peter Greenaway could give it the Prospero’s Books treatment, layering window upon window of atrocity across the screen to a ferociously seesawing string accompaniment from (one can dream) Michael Nyman. I enjoy playing this mental game because Salò feels to me like such a filmmaker’s film, one that communicates in pure cinematic terms Pasolini’s dismay at the state of this modern world. It’s no coincidence that Salò‘s pianist, the one true artist among this bunch, checks out before the end, jumping from a second-story window. Her departure from the scene is a signal, maybe, that the worst is yet to come–the equivalent of that Gaspar Noé title card that read, “You have 30 seconds to leave the theatre.” Or it’s possible that she’s just Michael Haneke’s ideal audience member, the one spectator involved in the whole sordid affair who has the courtesy to stop watching the horrors before her eyes.

If you do walk out of Salò early, you’ll miss the director’s final authorial flourishes, which are significant. Salò‘s last sequence involves the murder of the innocents, who are burned, hung, branded, and mutilated in a walled courtyard outside the building. Their tormentors switch roles between participating physically in the maimings and killings and watching through spyglasses from a convenient vantage point indoors. Pasolini shot these scenes from a camera perched on a platform overhead, peering into the action through a long lens that emphasizes the spectator’s distance from the events even as it directs the audience’s gaze precisely towards them, the better to see the eyes gouged and the nipples burned. At one point, the Duke, thrilling to the spectacle outside, inexplicably flips his binoculars and peers through them the wrong way. Pasolini cuts to a wide-angle point-of-view shot that, for the first time, depicts the entire grisly setting. It has the effect of making the participants look like actors on a stage, or tiny pawns in their own low-rent Marienbad.

I’m not sure Pasolini ever means to scold audience members outright for their role in all this, but this is the shot that has me looking askance at myself, sprawled on my futon couch in front of my 46-inch HDTV with the first-world problem of a FILM FREAK CENTRAL Blu-ray review deadline staring me in the face, and wondering at my happy complicity in bringing to fruition the industrial world Pasolini rails against. In another exquisitely reflexive touch, Pasolini ends the film after one of the young guards, apparently sick of the dirge from Carmina Burana that’s been playing over the mayhem, simply reaches for the radio and changes the station. (Then he dances stupidly with his little buddy.) Partly because of the sexual, social, and political subtext and partly just because the geometry of the image has by these closing shots evolved to the point where even the art direction officially freaks me out, this is, for me, one of the spookiest passages in cinema. There’s an abrupt cut to a shot of the back of the magistrate’s chair, a dark oval distended by a wide-angle lens that echoes the view through the magistrate’s binoculars, that chills me every time.

It’s an accident of history that Salò, of all possible projects, became the ultimate expression of a filmmaker who might otherwise have been best known by cinephiles simply for his affinity for the working class, or perhaps for his definitive filmed version of the Christ story. Does Salò endure because it’s a bitter attack on the ruling class and a consuming philosophical statement that plumbs the depths of Italy’s national soul? Or does it remain in the spotlight because of its reputation as an arty X-rated movie to be reckoned with–one that, to borrow the parlance of obscenity law, appeals to the prurient interest? The answer is a little bit of both. It’s a serious work of politics and poetry that maps easily to the Abu Ghraib prison scandals and even the Occupy Wall Street protests. (You could say it’s a movie about the 1 percent.) It’s also a prank; a thumb in the eye of authority, challenging viewers and riling censors for decades. Salò offers a rigorous exploration of the line between art and obscenity. What wins out in the end is the steadiness of Pasolini’s hand in crafting this indulgent disquisition–his assertion of formal mastery, mordant humour, and moral authority in the face of despair.

THE BLU-RAY DISC

I spent a lot of time with Salò over the last couple of weeks, and I was surprised at how quickly it grew in my estimation, given that I was impatient and somewhat annoyed with it on first viewing. I give partial credit to Criterion’s luminous HD presentation. The picture here is miles ahead of the 1998 Criterion DVD release, apparently ported from a LaserDisc master that much older, which was a murky affair with a colour balance so far in the green that it seemed possible Salò took place in The Matrix. The current 1.85:1, 1080p transfer features a dramatically refined palette that favours natural flesh tones and neutral backgrounds. Framegrabs available at the usual sources online (DVDBeaver, etc.) show that the current Region B release from the BFI still leans towards the cool end of the spectrum, suggesting there may be some precedent for greener/bluer colour grading. That’s a question for the archivists, perhaps–Criterion says its HiDef master is a 2K scan of an interpositive (IP) struck from the original camera negative, but it’s unclear what reference was used for the colour decisions. (Cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli died in 2005.) Criterion generally lists the off-the-shelf hardware and software used in transferring a film in a given disc’s liner notes, and it would be nice if they would regularly expand that section with some thoughts on colour timing, especially if original lab notes or properly-timed prints were used as reference material.

I don’t mean to imply that there’s anything wrong with the Criterion image, which is a revelation. Grain is accurate and natural, colours are uniformly rich but not overly saturated, and the film has been mostly cleaned of dirt, scratches, and damage without negatively impacting detail. Blacks may be crushed a bit in the shadowed areas of darker scenes, but not distractingly so. The scourge of edge enhancement is sometimes detectable in exteriors depicting characters and buildings silhouetted against the sky, but it’s not troublesome.

The sound quality of the uncompressed LPCM 1.0 Italian language option is excellent and undistorted; almost all of the background noise has been eliminated without compromising the quality and range of the dialogue, music, or effects. The Dolby Digital 1.0 English-language dub is not only technically inferior but reflects a weaker mix, with more audible noise, muddier Foley, and the music-and-effects track pushed below the dialogue in the mix. Moreover, there’s a harshness to the English audio that may owe to slightly distorted dialogue recordings, the aggressive Dolby Digital compression, or both. As usual, subtitle-haters will appreciate the gesture, but everyone else will stay away. Subtitles, for what it’s worth, are available in English only.

Some viewers have a beef with Criterion over a short bit of film missing from its releases but included in the BFI editions, in which a poem by Gottfried Benn is quoted. Criterion confirmed that the scene in question appeared neither in the IP source (and thus wasn’t a victim of some kind of glitch during the video mastering process) nor in prints of the film held by the Pasolini Foundation in Rome and essentially threw up its hands, calling the scene’s provenance a “mystery.” Well, OK. It is well established that Pasolini cut the film fairly aggressively before its release, and it would certainly be interesting to see some of that deleted material. Unfortunately, none of it was excavated for this go-round.

I can imagine a number of ways to approach the extras for a title like Salò. The Disney version would have a 10-minute infomercial for the Pasolini Foundation and a behind-the-scenes documentary featurette on the theme-park ride. Universal would offer an onscreen running tally that ticks upward every time someone dies, cries, has sex, or screams “Mangia!” The nerds at Criterion have opted for a defensive posture, curating a selection of documentaries and talking-heads that argue single-mindedly for the film’s status as Serious Art. First up is the 33-minute documentary “Salò: Yesterday and Today” (1080i, 2002), a fairly definitive compilation of vintage footage of Pasolini at work shooting Salò and interviews with Pasolini and others that testify to the easy camaraderie on set, but also make his intentions clear. As actress Hélène Surgère puts it, “When I saw the film, I wondered how we’d made something so awful without realizing it.” Her recollections of “Fascists parading in Boulogne” in 1975 help establish that Pasolini’s concerns were rooted in contemporary politics, rather than history.

Next up is the 23-minute “Salò: Fade to Black” (1080i, 2001), presented in HD (apparently upconverted from a good PAL master). This one, notably, brings other directors to Pasolini’s defense, such as John Maybury (“The film…undermines all of those expectations you have about what’s erotic”), Catherine Breillat (“It’s one of the most important movies in the world”), and Bertolucci (“I remember saying that the film was atrocious and sublime”). The short also lays out some of the Italian cultural context that helps international viewers understand Salò, and scholar David Forgacs makes the case for Salò as “anti-pornography.” The 40-minute “The End of Salò” (1080i), directed by Mario Sesti, is an artier affair that opens by cutting between interviews with actress Antinisca Nemour (one of the victims) and Paolo Bonacelli (the Duke). (Nemour seems a touch mixed on her experience with Pasolini, volunteering that the atmosphere during the shoot made it feel real at times, but she notes that when she expressed frustration at Pasolini’s aloofness on set, he made a point of taking her to lunch the next day.) Other interviewees include uncredited screenwriter Pupi Avati (who claims never to have seen Salò), second assistant director Fiorella Infascelli (who says the scene of cast and crew dancing together was intended for the end of the film), assistant editor Ugo Maria de Rossi (who says it was destined for the beginning), production designer Dante Ferretti, director Aleksandr Sokurov, and photographer Fabian Cevallos, who managed to wrangle permission to shoot behind the scenes on Salò and ended up with the last pictures ever taken of Pasolini.

Criterion conducted its own 11-minute interview with Ferretti (in HD and Italian with English subtitles), as well as a 27-minute interview (in HD and English) with Jean-Pierre Gorin that begins with the question, “Why should one see Salò?” Gorin, the director who co-founded the Dziga Vertov Group with Jean-Luc Godard, is a heavyweight in film-crit circles (and a professor at the University of California in San Diego), but his remarks here are accessible and relatively unburdened by theoretical jargon. “There’s nothing hot about Salò,” he observes. “There’s something stingy and cold.” The defense of Salò is furthered by the six critical essays in the thick insert booklet, where Neil Bartlett, Catherine Breillat, Naomi Greene, Sam Rohdie, Roberto Chiesi, and Gary Indiana all tackle the film. Said booklet also features excerpts from a diary kept during the shoot by Pasolini’s friend Gideon Bachmann, which was originally published in SIGHT & SOUND. Lastly, there’s an English-language trailer, in 1080i. It may be hard to imagine Salò playing at a theatre near you, though this does give an idea of how the film’s distributor decided to market it, first by changing the title to simply 120 Days of Sodom. (Actual onscreen text: “Don’t see The 120 Days of Sodom.”)

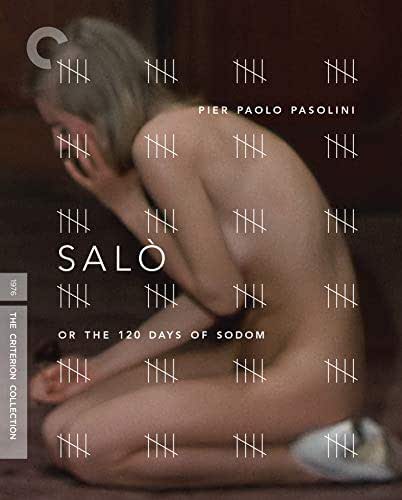

108 minutes; NR; 1.85:1 (1080p/MPEG-4); Italian 1.0 LPCM; English subtitles; BD-50; Region A; Criterion

![Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) [The Criterion Collection] – Blu-ray Disc](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/salo1.jpg?fit=800%2C434&ssl=1)