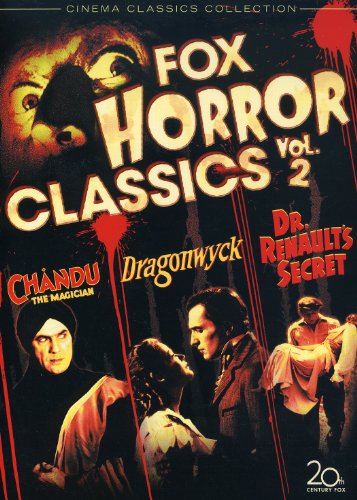

CHANDU THE MAGICIAN (1932)

***½/**** Image B- Sound C Extras A-

starring Edmund Lowe, Bela Lugosi, Irene Ware, Henry B. Walthall

directed by Marcel Varnel and William Cameron Menzies

DRAGONWYCK (1946)

**/**** Image A Sound A Extras B+

starring Gene Tierney, Walter Huston, Vincent Price, Glenn Langan

screenplay by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, based on the novel by Anya Seton

directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz

DR. RENAULT’S SECRET (1942)

*/**** Image A Sound A- Extras B

starring J. Carrol Naish, John Shepperd, Lynne Roberts, George Zucco

story by William Bruckner and Robert F. Metzler

directed by Harry Lachman

by Alex Jackson SPOILER WARNING IN EFFECT. I confess to feeling a little insecure while reading the entry for Chandu the Magician in Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide, wherein the learned film historian derides Chandu as “disappointing” and “not as good as most serials in this genre, and even sillier.” The suggestion is that he’s wholly sympathetic to the material and was actually hoping to see a good movie before being “disappointed.” Mr. Maltin may very well be in a better position than me to determine the relative merits of Chandu the Magician. Speaking as a layman, I found it to be sublime pulp fiction. Prototypical of George Lucas’s Indiana Jones and Star Wars franchises, the film is remarkably shameless in its goofiness, never veering into self-deprecation or camp. It’s one of those rare pop entertainments that genuinely make you feel like a kid again.

by Alex Jackson SPOILER WARNING IN EFFECT. I confess to feeling a little insecure while reading the entry for Chandu the Magician in Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide, wherein the learned film historian derides Chandu as “disappointing” and “not as good as most serials in this genre, and even sillier.” The suggestion is that he’s wholly sympathetic to the material and was actually hoping to see a good movie before being “disappointed.” Mr. Maltin may very well be in a better position than me to determine the relative merits of Chandu the Magician. Speaking as a layman, I found it to be sublime pulp fiction. Prototypical of George Lucas’s Indiana Jones and Star Wars franchises, the film is remarkably shameless in its goofiness, never veering into self-deprecation or camp. It’s one of those rare pop entertainments that genuinely make you feel like a kid again.

The eponymous Chandu (Edmund Lowe) is a former army captain who has spent several years in India studying the fine art of hypnotism and becoming a skilled yogi. Chandu’s training complete, his master dispatches him to Cairo to do battle with the devious Roxor (Bela Lugosi). Chandu’s brother-in-law Robert Regent (Henry B. Walthall) has just devised an experimental death ray and Roxor has kidnapped him so that he may use it to take over the world. Chandu’s superpower is a lot cooler than it sounds: In addition to controlling other people’s minds, he is able to conjure up hallucinations. Chandu, for example, will transform a gun into a snake and the snake back into a gun. To depict this, the gun and the snake were photographed separately and combined using a dissolve. In their primitiveness, these special effects remind of the experimental nickelodeons of cinema’s infancy, when filmmakers were discovering the potential of the art form. Accordingly, Chandu the Magician has a playfulness to it. The sets are genuinely impressive and there is a kind of epic scope to it. You don’t feel cheated, or like you are watching a substandard product. But in some key ways, the film looks charmingly homemade. It has the same appeal as the “Sweded” videos in Michel Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind.

Chandu the Magician was co-directed by Marcel Varnel and William Cameron Menzies; Varnel handled the actors while Menzies was responsible for the technical aspects. I’m fairly new to Menzies, but I found Chandu the Magician to be much frothier than at least some of his subsequent work (Things to Come, Invaders from Mars, and though it would be stretching the auteur theory as he was only one of several directors on both projects, The Thief of Bagdad and Duel in the Sun). However much credit is due Varnel for the film’s campy charm, I hope I can be forgiven for attributing the lightness of Chandu the Magician to the mildly self-reflexive fact that, because he’s an illusionist, Menzies is able to see his hero Chandu as a fellow filmmaker.

Surprisingly, the most refreshing thing about Chandu the Magician is its kinkiness. Realizing that no matter how much he tortures him, he will never get Regent to build him the death ray, Roxor kidnaps his teenage daughter Betty Lou (June Lang) and threatens to sell her into slavery. She gets as far as the marketplace in Cairo, where she is stripped down to her clingy slip and displayed screaming to an appreciative audience of dark-skinned Arabs. Apart from the Yellow Bastard sequence in Sin City, I don’t think I have ever seen a pop entertainment so fully exploit the sadomasochistic underpinnings of the damsel-in-distress scenario. Oh, the threat of miscegenation is nothing new–it’s just that it’s not usually played for titillation. The audience isn’t given any other way to read the scene. If Chandu doesn’t rescue her in time, she is going to be defiled by a filthy Arab.

Lang’s Betty Lou is a gorgeous blonde with an obnoxious whiny voice and not much in the smarts department. She seems to forget about everything that has happened to her the moment Chandu rescues her. As with Jessica Alba in Sin City, her childlike qualities simultaneously objectify her and make her sympathetic; the scene works subversively as pornography while also working conventionally in action-adventure terms. (Long live the pre-Code era, eh?) Hardly gratuitous, this sex slavery subplot–along with a scene where he blinds his underlings with a hot poker–helps to vilify Lugosi’s Roxor. Without it, the death ray stuff could easily be dismissed as kiddie camp.

Because the film goes so far in painting Roxor as an ice-cold, heartless bastard, we have an emotional stake in his defeat. Yet even then, as is often the case with these movies, you may find yourself empathizing more with the villain than with the hero. Lowe is perfectly fine as Chandu, but the character is too happy, too unburdened, too heroic to identify with. I’m sure this is largely a projection on my part, but Roxor has a certain pathos and self-hatred that makes him a more relatable human character. After his death ray is built and fully operational, Roxor delivers a surprisingly poignant monologue about his plot to take over the world that reminds a lot, as it happens, of Lugosi’s speech in Bride of the Monster, which Ed Wood suggests was a coded cry of defiance at how Hollywood had chewed him up and spat him out.

Near the end of the film, Chandu begins to hypnotize Roxor into letting go of the lever controlling the death ray. Roxor fights back with all his willpower. “You can’t move that lever,” Chandu says to him. Pouting like a two-year-old, Roxor petulantly declares, “I’ll move it now!” The film’s provocative suggestion is that perhaps Roxor wants to destroy the world just because he can. Being evil simply means being free of moral responsibility–a responsibility that is easier for men like Chandu to uphold.

***

Clocking in at a reasonable 103 minutes, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1946 directorial debut Dragonwyck feels much longer than it really is. I don’t mean that as a dig necessarily. The film fills you up like truly epic movies do. When it’s over, you know you’ve seen something. This is likely attributable to the fact that it values the narrative above everything else. Mankiewicz is more interested in telling a story from beginning to end than in developing a perspective towards or an impression of his subject matter. He’s certainly not very interested in developing a mood or an environment for us to inhabit. My grandparents tell me they can’t understand why anybody would want to watch a movie more than once. After you’ve seen it, you know what’s going to happen! Definitely a picture from a bygone era, Dragonwyck is the sort of movie nobody would want to see twice. Even if they enjoyed it.

The film has the basic appeal of a late-Forties, A-list literary adaptation. It’s worth watching, to some extent, for Walter Huston, Gene Tierney, a strange character performance by Jessica Tandy, and a relatively straight one from Vincent Price. At Universal, Price built his name and reputation specializing in horror films like The Invisible Man Returns, but when he relocated to 20th Century Fox in 1940, his first role was as Joseph Smith in Brigham Young: Frontiersman! Price does a fine job in Dragonwyck. He’s understated, believable, and sufficiently acquits himself of his reputation as a ham. Still, outside of sheer novelty, who wants to see Vincent Price play it straight? The pleasures that Dragonwyck has to offer are pretty meagre compared to the transcendent kitsch of Chandu the Magician.

Miranda Wells (Tierney) is a simple farm girl who can’t resist taking up an offer from her distant cousin Nicholas Van Ryn (Price) to work as an au pair at his New York estate, Dragonwyck. Though she enjoys the sophisticated life of 19th-century aristocracy, Wells is disturbed to discover that an old-fashioned feudal system is still in place in upstate New York, with landowner Van Ryn lording over tenants who have to pay him a tribute for the right to farm the land. As she learned from her (progressive?) father (Huston), every man is entitled to the fruits of his labour. After Van Ryn’s wife passes away, Wells returns home. She finds herself pining for Van Ryn, however, and when he arrives at her doorstep to propose marriage, she doesn’t hesitate. Once they’re married, she realizes her mistake: Not only is her new husband a feudalist, he’s an atheist and a Darwinist as well! He sneers at her sympathetic hiring of a crippled Irish housekeeper (Tandy) and thinks her faith in God is nothing short of childish. Wells subsequently discovers that he murdered his first wife because she was unable to produce a male heir (and has similar plans for her).

The film seems to have strong, perhaps ironic (in light of the anti-atheist sentiments) Marxist underpinnings. I know that “Marxist” is at this point an overused buzzword, but I mean it in a fairly literal sense in this instance. The film very vividly and blatantly illustrates the rudimentary Marxist concept of alienation. Labour should ideally be a manifestation of one’s “essence” or “individuality,” but in a capitalist society, this association is lost. I’m treading fairly carefully here, but Dragonwyck was inspired by the Anti-Rent War of 1839 in upstate New York, which was within a decade of the publication of The Communist Manifesto. The film’s relationship to Marxist thought is considerably more substantial than a basic empathy with the working class. This would be a far more subversive picture if Mankiewicz didn’t insist on making Van Ryn’s atheism a major cornerstone of his villainy.

Dragonwyck is less pro-communist and anti-capitalist than pro-American and anti-Hitler. As the film’s moral centre, the Lockean ideas espoused by the Huston character are treated as “self-evident” truths. He specifically enumerates these rights as the rights of all Americans and clearly believes they were literally endowed upon us by our Creator. As an atheist, Van Ryn is incapable of subscribing to this moral principle, or frankly any moral principle at all. He owns this land because he inherited it from his father, who inherited it from his father who inherited it from his father, et cetera; the only reason he is rich is because his bloodline makes Van Ryn naturally superior to the riff-raff. The strong deserve to live on and prosper simply because they are strong, and the weak (in particular, crippled Irishwomen like Tandy) deserve to die off simply because they are weak. The only law the natural world obeys is that of survival of the fittest.

Van Ryn’s atheism is further condemned by a couple of rather half-assed plot elements. Dragonwyck is haunted by one of the Van Ryn ancestors and this ghost arrives whenever Van Ryn has murdered or plans to murder one of his wives. Though Dragonwyck was the rare “haunted house” film of the era to not explain away its supernatural elements, this is spirituality in its most palatable form–seeing ghosts is only a few steps removed from hearing the voice of God condemning Van Ryn for his wicked ways. Van Ryn also reveals late in the film that he is a “drug addict,” presumably because his lack of belief in a higher power has left him with a void in his life. (And once the film gets to the drug addiction, the piling-on becomes inexcusable.)

I guess there’s novelty to the film’s religiosity, a more substantial novelty than that of a dramatic Vincent Price performance. Atheists aren’t exactly an oppressed group in the movies. Occasionally you’ll see a film where somebody champions an atheistic viewpoint and by the end sees the error of their ways and learns to believe in a higher power (i.e., Simon Birch, I Am Legend, Signs). In those cases, their cynicism is merely something to be pitied. I have not seen many films where atheists are as overtly demonized as they are here. Dragonwyck certainly isn’t less reductive than an overtly anti-Christian film like Silent Hill, but the idea that atheists are the villains for once and the God-fearing Christians are the heroes is a mildly refreshing change of pace.

Could anybody really buy into this? By “anybody,” I’m not talking about an undemanding, right-leaning, plebeian audience. I’m talking about you, elite FILM FREAK CENTRAL reader, you who genuinely loves movies and has discerning taste and will no doubt regard Dragonwyck‘s philosophy as jejune. Is there an angle at which we might view the film that would render it a misunderstood masterpiece? The rationale that this was 1946 and people were dumber and more religious back then and it’s necessary to put it in the proper historical context cannot be used. Indeed, being made in 1946 is the only thing giving the film its modest charm. Nor can Dragonwyck be truly appreciated as camp–as authentic “I Married an Atheist” propaganda. It’s not that outrageous, and again there’s minimal pleasure in doing so. I guess your only option is to appreciate it specifically for the compromises Mankiewicz had to make in transforming the intrinsically socialist subject matter into something palatable for American audiences. (A precursor to his 1958 adaptation of The Quiet American?) In which case, I can only counter that it would be better to watch a real movie instead.

There’s a temptation to give Dragonwyck the benefit of the doubt simply because it’s so tastefully made and Mankiewicz’s name is there as writer/director. 1942’s Dr. Renault’s Secret yields no such temptation. This is a justifiably-forgotten B-movie of almost no worth, notable mainly for its pretentious and surprisingly nullifying racism. Because the film considers itself to be above escapist entertainment, all that we have to sustain us are its “ideas”–and these ideas are distressingly racist. It’s too smart to be bad and not smart enough to be any good.

While I’m sure that many won’t be convinced by this line of reasoning, I feel that the slobbering Arab rapists of Chandu the Magician deserve a pass because they serve no higher purpose than to appeal to the prurient interests of the viewer. The marketplace scene is based on the assumption that the audience will see an Arab rapist as even more threatening than a white rapist. Chandu the Magician is indeed a racist film, but when it comes to exploitation and sensationalism, where strong effect is all that matters, political correctness and morality are permitted to take a break. If that sounds outrageous, I’ll offer that the offensiveness of the film as a whole is curbed somewhat by the fact that Chandu learns actual magic while in India and Roxor makes copious references to the Old Testament. What I’m saying is that it doesn’t marginalize or dismiss Eastern culture and mythology, and if it does it diplomatically takes the Bible down with it.

Inexperienced viewers may regard Dr. Renault’s Secret as the superior film since it acts more sympathetic towards its monster and places a greater emphasis on characters and emotions than on plot. However, this is a film uncomfortable in its own skin and too refined and sophisticated to have its outdated racist attitudes dismissed as unenlightenment (unlike Chandu the Magician). The monster of the film is Noel (J. Carrol Naish), an immigrant from Java employed by the scientist Dr. Renault (George Zucco). Noel is in love with Madeline (Lynne Roberts), Renault’s niece, but she is engaged to Dr. Larry Forbes (John Shepperd). Overcome with jealousy, Noel stalks Forbes with the intent of killing him. By the end of the film, Dr. Renault’s horrible secret is revealed: Noel is actually a shaved gorilla who has undergone brain surgery. And now his animal instincts are taking over.

The real villain of the piece is Dr. Renault, of course. We pity poor Noel, an innocent who was made a monster–but this is precisely where the film becomes problematic. This idea that everybody is pretty much convinced that a shaved gorilla is just Javanese is a priori racist. After explicitly associating an ethnic group with apes, the film goes so far as to say that it’s immoral to integrate these non-whites into civilized society. Noel does not have the intellectual capacity to comfortably co-exist with his racial superiors, a notion cruelly illustrated by his unconsummated infatuation with Madeline. It’s not only Dr. Renault’s amoral pursuit of scientific knowledge, then, that has made Noel an abomination in the eyes of God, it’s his naïve social progressiveness, too. If that’s not enough to sour you on the prospect of Dr. Renault’s Secret, know that in addition to being ridiculous, it’s singularly dull and unexciting.

THE DVD

It might go without saying, but grouping Chandu the Magician, Dragonwyck, and Dr. Renault’s Secret together in a “Fox Horror Classics” box set borders on false advertising. Chandu the Magician is a superhero adventure film, Dragonwyck is a Gothic melodrama, and Dr. Renault’s Secret ain’t no “classic.” Because 20th Century Fox apparently produced so few horror flicks back in the day, in raiding their vaults for suitable “horror classics” the studio had to get a little creative. To give credit where credit is due, these three films have long been unavailable on any home video format, and Fox has shown them a lot of love in honour of their DVD debuts.

The 1.33:1 full-frame presentation of Chandu the Magician begins with a disclaimer promising, “We have brought this film to DVD using the best surviving source material available.” A restoration comparison–which tells us that over a hundred hours of digital restoration work went into the film–reveals that the image has become more stable and contrasts more pronounced. Sadly, grain is still too heavy and, most grievously, there are frames missing throughout. At least Fox’s effort looks better than a cheap and simple Treeline Films direct transfer would. Worse is the weak Dolby Digital 2.0 mono audio, thick as it is with static and various age-related artifacts.

Bela Lugosi biographer Gregory William Mank’s attendant commentary was clearly written out and rehearsed beforehand. As he’s not working off-the-cuff and genuinely engaging with the film, the yakker has a somewhat unpleasant, plastic quality. This can be forgiven, though, as Mank stuffs the thing with information about pretty much everything and anything related to Chandu the Magician. We learn not only about the production, how it was received, and the careers of the principals–Mank also touches on the history of death rays in the movies and Nikola Tesla’s attempt to create one for real. When some camels materialize on screen, he amusingly rattles off a few camel facts. It might be as close as an audio commentary has ever come to emulating the experience of surfing Wikipedia. The track contains a number of great anecdotes, my favourite being about how film critic Val Guest got a job as a screenwriter under Marcel Varnel by arrogantly claiming in print that he could write a better movie than this mess. Varnel told him to put his money where his mouth is and Guest went on to have an illustrious career in the film business.

“Masters of Magic: The World of Chandu” (15 mins.) gathers together various B-movie buffs to reflect on the film. The general consensus is that the success of Chandu the Magician should be attributed to Menzies and Lugosi and that Lowe wasn’t much of a lead. Mank begins with this premise but goes on to acquit Lowe with a lengthy discussion of his career and by mentioning that a Chandu serial following this film with Lugosi in the title role was really quite terrible and a bad misuse of the actor. Ultimately, this featurette is superfluous in light of Mank’s exhaustive commentary and a bit reductive as well. Rounding out the platter is the aforementioned restoration comparison and a nice stills gallery.

Dragonwyck‘s 1.33:1 fullscreen transfer is nothing short of gorgeous, scrubbed clean of print damage and sporting potent blacks and whites. The Dolby Digital 2.0 mono audio matches the standard set by the video and is an excellent showcase for Alfred Newman’s booming score. DVD producers and film scholars Steve Haberman and Constantine Nasr record a feature-length yak-track that is objectively superior to Mank’s for Chandu the Magician. They talk a great deal about the novel, earlier drafts of the script, and scenes that were written and shot but taken out. We learn the backgrounds of all the major players and some of the minor ones. They tell us why Ernst Lubitsch took his name off the project and that Price considered Dragonwyck to be his best film when asked near the end of his career. The two men manage a more conversational tone than Mank and their dialogue has a more organic feel to it. Still, as an apologia for the film, it’s insufficient; Haberman and Nasr seem to take the anti-atheist stuff for granted, failing to acknowledge how this could alienate modern viewers.

The admiration for Dragonwyck here is not dissimilar to the admiration for Chandu the Magician: One is supposed to be great because it’s directed by Menzies and stars Lugosi, the other is supposed to be great because it’s directed by Mankiewicz and stars Price. Do you want to obsess over B-movie minutia or A-movie minutia? There’s something very superficial and uncritical about this type of movie love. I suppose the track is significant in getting me to wonder if my enjoyment of Chandu the Magician over Dragonwyck is born of some juvenile desire to stand-up for the goofy and bizarre over the dry and tasteful; “dry and tasteful” has an establishment flavour to it and “goofy and bizarre” is almost manifestly countercultural. I’m not sure I can legitimately claim that Chandu the Magician is more challenging or philosophically complex than Dragonwyck.

It’s hard to be fair when reviewing the DVD extras for movies you don’t much care for, but I found Dragonwyck to be an especial ordeal. The two vintage Dragonwyck radio shows are the most difficult to endure. The first, with Vincent Price and Gene Tierney and lasting about an hour, is a simple condensation of the film. As Dragonwyck is mostly narrative anyway, the pacing is sped up to the point where scenes lose even their modest emotional impact. The second, also with Price but with Teresa Wright replacing Tierney, lasts a mere half-hour but has been restructured so that Wells is telling the tale in flashback, and this helps enormously. Additionally, there’s a snippet of dialogue that was deleted from the film, making this episode of particular historical interest. “A House of Secrets: Exploring Dragonwyck” (16 mins.) is, of course, similar to the “Masters of Magic” featurette on Chandu the Magician in that it more or less repeats information better disclosed in the audio commentary. As Dr. Drew Casper is one of the interviewed, I’m grateful that he wasn’t commissioned to record the commentary proper. Additional features: an isolated music score; a restoration comparison; Dragonwyck‘s theatrical trailer; and no fewer than four still galleries (for advertising, U.K. lobby cards, behind-the-scenes, and production).

On DVD, Dr. Renault’s Secret looks every bit as good as Dragonwyck. Contrast is depressingly tight in the 1.33:1 full-frame transfer and detail is fine. Dialogue is clear enough in Dolby 2.0 mono, although the track is noticeably weaker than that of Dragonwyck. “Horror’s Missing Link: Rediscovering Dr. Renault’s Secret” (16 mins.) is another fawning featurette, less redundant than the others in this set (in that it isn’t upstaged by an audio commentary) but more annoying in that it’s painful to see such a terrible film treated with such reverence. (Somebody actually says, “Dr. Renault’s Secret is one of the best-kept secrets of the horror genre.”) The picture was loosely based on the Gaston Leroux novel Balaoo, and we get some clips from two lost silent versions of the story–which is welcome, though I could have done without the pained comparisons to 20th Century Fox’s own Planet of the Apes. A restoration comparison, Renault’s theatrical trailer, and three still galleries–advertising, lobby card, and production–round out the disc. The packaging for “Fox Horror Classics, Vol. 2” includes an informative insert detailing the history of all three films.

- Chandu the Magician

71 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); CC; English, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Fox

- Dragonwyck

103 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono), Spanish DD 2.0 (Mono); CC; English, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; Fox

- Dr. Renault’s Secret

58 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono), Spanish DD 2.0 (Mono); CC; English, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Fox

![Dirty Harry [Ultimate Collector's Edition] - Blu-ray Disc FFC Must-Own](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/6a0168ea36d6b2970c016304cd768d970d-600wi.gif?resize=100%2C91&ssl=1)