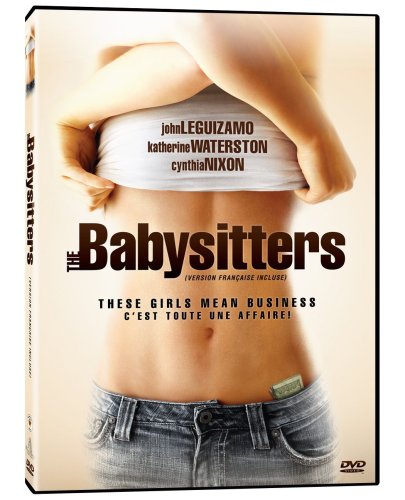

**/**** Image A- Sound A- Extras B+

starring John Leguizamo, Katherine Waterston, Cynthia Nixon, Andy Comeau

written and directed by David Ross

by Alex Jackson Shirley Lyner (Katherine Waterston) is not only anxious about getting into the right college, she's worried about how she's going to pay for it, too. Unlikely inspiration hits after she babysits for Michael and Gail Beltran (John Leguizamo and Cynthia Nixon). While driving her home, Michael takes Shirley to a diner for coffee and they begin to talk. When Michael first met his wife, she was a boldly sexual "party girl," and he misses that spark. He asks if Shirley has a boyfriend and she says "no." An outburst from a nearby group of teenage boys provides a hint as to the reason, likewise an obsessive-compulsive tic whereby Shirley reorganizes the condiments on the counter. She doesn't seem to view herself as very sexy or lovable; since school has always taken precedence over boys for her, she is rather flattered by the attention Michael is showing her. They have sex. Terrified to confront his infidelity and his exploitation of this young girl, Michael generously tips Shirley, shyly reminding her that he has a wife and kids. This gives Shirley a great idea: she'll recruit her friends to prostitute themselves out to middle-aged men from around the neighbourhood.

|

A blurb on the front-cover of the film's Canadian DVD release calls The Babysitters "a female inversion of Risky Business." This is an intriguing description for a number of reasons. First off, The Babysitters presents itself as an "independent"–"independent" of studio financing and of all the compromises that come with it. "Female inversion of Risky Business" is a phrase that really helps cut through that silly façade by emphasizing the film's crassly commercial, high-concept origins. If the script for The Babysitters wasn't pitched to some Hollywood Griffin Mill with the line "female inversion of Risky Business," you can certainly bet that the finished product was hyped to a distributor this way.

And as "a female inversion of Risky Business" that seems reluctant to brand itself as such, The Babysitters is disappointingly chaste and self-serious. The characters appear to always have sex with their clothes on. The sole shot of nudity has Shirley baring her breasts to Michael. While I'm sure that somebody somewhere could justify its inclusion as marking the point where Shirley has completely transformed herself into a commodity, I'm sticking with the belief that the film–in light of its subject matter–needed it to ensure an R rating, for credibility's sake. In addition to being chaste, The Babysitters is moralistically dull. The hook-ups look sloppy and unsatisfying–reminding a lot of the tryst between Joan Allen and Jamey Sheridan in Ang Lee's The Ice Storm, as a matter of fact. We see that the men have regained their adolescence, in a sense; they get involved in childish cloak-and-dagger, Project Mayhem-like shit to preserve the prostitution ring. But there's never a hint of the elation that the regression may produce. For the life of me, I couldn't understand why they kept coming back for more.

To be fair, the "babysitter prostitution ring" has a serious satirical point, and writer-director David Ross did not make this film to titillate audiences. He's criticizing the so-called American dream and the over-emphasis the middle class places on material success. Why does Shirley want to get into a good college? So she can get a high-paying job like Michael has. Why does Michael want to sleep with Shirley? To recapture the joy and sense of purpose that is not fulfilled by his job and its attendant material comforts. It's a great point–great enough that I feel a little protective of the film and sort of want to shield it against attack. Unfortunately, The Babysitters in and of itself doesn't warrant a strong defense. By formal standards, the script is overwritten and takes too many shortcuts. The first scene uses voiceover and then goes to flashback. I thought to myself, Holy shit, everything Syd Field and Robert McKee told you never to do! (It probably goes without saying that Ross wasn't trying to be subversive or inventive in so doing.) More significant is the simple fact that this "female inversion of Risky Business" isn't as good as Risky Business.

***

Risky Business gave us the iconic image of Tom Cruise in his socks, underwear, and Ray-Bans air-jamming to Bob Seger's "Old Time Rock and Roll." It also contributed to film culture the famous sex scene on the subway, which is routinely recognized on lists of mainstream cinema's finest. So the movie is a popular hit and delivers on that level. And yet, it received a four-star rating from Roger Ebert as well. Granted, he's always been fairly generous with his highest rating, but in 1983 a four-star rating from Ebert still signified something out of the ordinary. Risky Business works on a level deeper than but additional to that of the sexy yet conventional crowd-pleaser. Like The Babysitters, Risky Business is a critique of Americans' overemphasis on material success. Unlike The Babysitters, it doesn't use the critique as an excuse to be boring.

The joylessness of The Babysitters comes to a head with the obligatory rape scene that informs us it's all fun and games until somebody gets hurt. Risky Business never had to rape its whore. The film celebrated and used Rebecca De Mornay as a sex object but nevertheless found a way to get the audience to empathize with and even respect her on her own terms. There are a number of genuinely startling moments where she confronts the spoiled and naïve Cruise on his air of class superiority, indicating the myriad ways in which she is the smarter, more sophisticated of the two and actually exploiting him, as well as the manner in which she protects her mental well-being while selling herself as a male sexual fantasy. It's a sophisticated film, understanding "The Prostitute" as an invented construction, an icon, and a "thing" while simultaneously understanding that a flesh-and-blood human being inhabits the role. Dimwittedly wholesome, The Babysitters only understands the latter point.

There is another major point to be made about this "female inversion of Risky Business." A surprising number of critics have derided the film as immoral or disgusting. "I'd call it a depressing soft-core porn flick, but that overstates its titillation factor," writes Kyle Smith of the NEW YORK POST. "Mainly it's just icky." Ann Hornaday of the WASHINGTON POST brands it "a loathsome slice of exploitation at its most cynical and crass." Of course, it isn't really anything of the sort. The only reason for the complaint is that the storyline involves teenage girls selling themselves (and each other) to middle-aged men. If the genders were reversed, the outrage would evaporate. These complaints evince a strain of misogyny far more grievous than that depicted in the film in their suggestion that women are inherently dumber and more psychologically fragile than their male counterparts and thus more vulnerable to exploitation.

"But wait," I hear you saying, "Tom Cruise was a pimp in Risky Business. He was selling women, he never had to sell himself." Quite right. If you want to go there, we could just as easily call The Babysitters "a female inversion of Loverboy," the 1989 film where Patrick Dempsey plays a pizza-delivery boy who inadvertently becomes a Beverly Hills gigolo. I'd be surprised to find anybody who seriously believes the Dempsey character is being exploited. To be completely fair, he is slightly older than the teenagers of The Babysitters, but–spoiler alert for both films–he's young enough to see a parent appear on his client list as Shirley does. There seems to be a double standard here, denying teenage girls the ability to be stupid, greedy, and amoral while affording teenage boys that very privilege.

Somewhat covertly riding the double-standard bullet train, SLANT's Nick Schager complains about "the fact that male filmmakers still view teenage girls in such offensively reductive ways." This is a more difficult charge to argue against. By their very nature, all films–and all forms of visual art, for that matter–are necessarily "reductive." Still, I at least view Ross's depiction of teenage girls as leaning towards not so much misogyny as mere misanthropy. The best line of the film is one of the very first, with Shirley claiming, "Paid fellatio isn't that much more humiliating than flipping burgers." I'm sure most will see this as evidence of how she devalues her sexuality. I prefer to see it as evidence of her supreme narcissism.

The notion that Shirley and her friends will have sex for money exclusively because they're flattered that adult men regard them as some kind of beauty ideal is admittedly hard to take. Yet I can accept that it's that flattery–combined with the idea that they have their own business and make their own rules, get paid lots for relatively little work, and can relate to other adults on a near equal peer level (the men have money, the girls have their sexuality, and in trading the two they have a truly egalitarian relationship)–that motivates them to do what they do. These girls aren't just male fantasies, they're the product of a culture where financial and material success is hailed as the endgame. There is a nugget of greatness in The Babysitters. Had it only the wit to realize its satirical bite, I might be motivated to stand up for it more.

THE DVD

Peace Arch brings The Babysitters to DVD in a 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer that renders Michael McDonough's uselessly beautiful cinematography with apparent fidelity. Blacks and colours are dynamic and grain is appropriately filmlike. The Dolby Digital 5.1 audio is pretty utilitarian but generally matches the image in potency. Ross and Waterston record an agreeable yak-track, doling out the usual praise for the performances and discussing character motivation while offering behind-the-scenes anecdotes, notes on the filmmaking, et cetera. Ross informs us that they switched from Fuji stock to Kodak after Shirley loses her virginity in order to imbue the film with "a slightly more saturated look." I'm reminded of Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell's comments on the "hyper-refinement" in Babel. I mean, who is possibly going to notice? In celebrating actor Denis O'Hare, Ross says that he has "been in every good movie of 2007." Said movies would be Michael Clayton, A Mighty Heart, and Charlie Wilson's War–harshly exposing the filmmaker's aspirations to join the middlebrow. To the commentators' credit, however, they nearly justify the random quirk of Shirley's obsessive-compulsive behaviour, calling it shorthand for how she can never be "out of control." Still strikes me as sloppy screenwriting, though, considering how quickly her tics are discarded.

"Making The Babysitters" (8 mins.) is a tad more substantial than your usual making-of featurette. The people behind this movie are too smart to have phoned it in, but not smart enough to realize when they're wrong. I was particularly aggravated by Leguizamo, who praises the film for not "trivializing" the subject matter like Risky Business did. Seriously, he says that! Everybody is too proud of the surprise ending, derivative of not just Loverboy but also an old urban legend archived at SNOPES.COM. Rounding out the disc: forced trailers for season two of "The Tudors", The Go-Getter, and Towards Darkness; an optional trailer for The Babysitters; and a digital copy of the film for portable viewing. Originally published: September 25, 2008.