BLUE CITY – DVD

ZERO STARS/**** Image C- Sound C-

starring Judd Nelson, Ally Sheedy, Paul Winfield, Scott Wilson

screenplay by Lukas Heller and Walter Hill, based on the novel by Ross MacDonald

directed by Michelle Manning

TOP GUN [Widescreen Special Collector’s Edition] – DVD + [Special Collector’s Edition] Blu-ray Disc

*/****

DVD – Image B Sound B+ Extras B

BD – Image B+ Sound A+ (DTS) A- (DD) Extras B

starring Tom Cruise, Kelly McGillis, Val Kilmer, Anthony Edwards

screenplay by Jim Cash & Jack Epps, Jr.

directed by Tony Scott

THE LOST BOYS [Two-Disc Special Edition] – DVD

***/**** Image B+ Sound B Extras C+

starring Corey Feldman, Jami Gertz, Corey Haim, Dianne Wiest

screenplay by Janice Fischer & James Jeremias and Jeffrey Boam

directed by Joel Schumacher

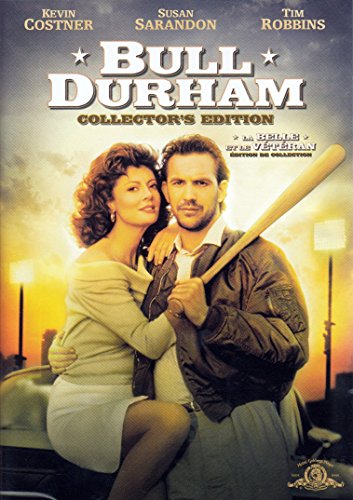

BULL DURHAM [Collector’s Edition] – DVD

**/**** Image B+ Sound B+ Extras B+

starring Kevin Costner, Susan Sarandon, Tim Robbins, Trey Wilson

written and directed by Ron Shelton

by Walter Chaw Released in 1986 and tonally identical to contemporary suck classics The Wraith and Wisdom, the Brat Pack travesty Blue City represents the nadir of a year that produced Blue Velvet, Down By Law, The Mosquito Coast, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, Sid and Nancy, Aliens, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, The Fly, Big Trouble in Little China, Something Wild, Mona Lisa, and Night of the Creeps, for starters. It’s the quintessence of why people remember the 1980s as a terrible decade for film, poor in every single objective measure of quality. Consider a central set-piece where our hero Billy (Judd Nelson) and his buck-toothed cohort Joey (David Caruso) stage a weird re-enactment of the heist from The Killing at a dog track that includes not only such bon mots as “I’m new at this! Give me a break!” but also the dumbest diversionary tactic in the history of these things as Joey tosses a prime cut on the track in front of a frankly startled/quickly delighted pack of muzzled greyhounds. Then again, it’s not a bad metaphor for the Me Generation and its blockbuster mentality. After cracking wise a few times in a way that makes one wonder if he’s suddenly become a Republican, Billy blows on the barrel of his gun in his best John Ireland-meets-Montgomery Clift and professional bad editor Ross Albert (the whiz kid behind Bushwhacked, The Beverly Hillbillies, and The Pest) cracks a little wise himself by cutting to a rack of hot dogs. Unfortunately, suggesting that Judd Nelson is gay as a French holiday is only mildly wittier than suggesting the same of clearly gay Tom Cruise. More on that when we get to Top Gun.

It’s so easy to punch holes in Blue City that it has the effect of rendering one speechless. It’s the antidote to the MST3K tendency–comes a point where a film is only as bad as it is. No amount of hooting at the endless, Wild Orchid interstitials of Nelson riding out to the Keys (or, better, when meaty love-interest Ally Sheedy rides bitch and dwarfs him like Blaster would Master) could make it funnier than it already is. Essentially what happens is that shiftless, disturbed layabout drifter Billy returns to the titular town (i.e., Miami) after an unexplained but cool absence of five years to learn that his father, the mayor, has been killed in the interim. “Un-fucking-believable,” Billy deadpans (or Nelson delivers in a flat, emotionless drone–it’s hard to tell), and off he goes to suss out who did the deed, vanilla crime boss Perry (the great Scott Wilson) his chief suspect. Petty acts of mild aggression and vandalism serve as the bait, and when Perry bites, Billy and Joey proceed to deliver their special brand of soulful, curiously pussified vigilante justice. The problems too deep-seated and numerous to enumerate, sufficed to say that they begin with casting Nelson as a tough guy and end with the rest of this godawful mess. Easily one of the worst films ever made and, as is the case with things of this vintage, simultaneously timeless and badly dated, count Blue City as the third of the Sheedy/Nelson collaborations (after The Breakfast Club and St. Elmo’s Fire) but the first that exists in an airless netherworld where, if there’s a tether that anchors it to its culture (the one that rejected it soundly, let’s not forget), it’s so filament-fine that I’m not inclined to try to ferret it out.

Which makes Top Gun–the top-grossing film of 1986 (edging out classics like “Crocodile” Dundee, The Karate Kid Part II, Star Trek IV, Back to School, and The Golden Child), as well as the prototypical blockbuster in the decade of the blockbuster–all the more difficult to discount. What was it in the bellicose air of the second Reagan term that turned a homoerotic Navy recruitment video (as if there could be any other kind of Navy recruitment video) into the most popular movie in the land? The question answers itself, of course, with old, literal bogeys resurrected for the purposes of punishment by the military might of the Red, White, and Blue just one year after John Rambo re-fought–and won–the Vietnam War and one year before two future-governors fight an invisible, technologically superior predator in the jungle. In other words, the wheels are coming off in the popular conversation as early as 1986 (third most popular flick that year? Platoon), as Reagan’s Eisenhower-era rictus stretched past snapback. The question of reality vs. televisual reality became–as it did at the end of the ’50s–the central issue of the period in cinema stretching from 1989 to 2001.

Before that, though, here’s Top Gun with its mawkish love story between hotdog pilot Maverick (Tom Cruise) and his RIO (his “bitch,” really), Goose (Anthony Edwards, who absolutely fucking kills it in two years’ time in Miracle Mile), interrupted tragically when Mav makes awkward love to Neanderthal-browed flight instructor Charlie (Kelly McGillis). Mav and Charlie’s silhouetted woo is indelible in my mind for the obvious head-size discrepancy, unmatched until the mantis-feeding of Winslet looming over DiCaprio in Titanic (concurrent with Sheedy pouncing like a mange-afflicted badger on quivering field mouse Nelson in Blue City, lest we forget). But the significance of Mav being separated, by a crowbar, from his beloved (“I miss Goose, I miss him, I want him here!”) and only then declaring his need for the masculinized Charlie (which Tarantino and Roger Avary pegged in their little monologue about the baseball-cap/elevator encounter in Tarantino’s Sleep With Me cameo) speaks for itself as much as Val Kilmer’s Ice Man, the actual repressed beloved who, not unlike the stirring refrain of Brokeback Mountain, wishes he could quit Maverick. After all, in their relationship, Charlie’s the man–constantly chasing Mav down, dressing butch, hulking over him, and taking him down a few notches when he gets too big for his britches. Top Gun is best read as a sexist reassignment of gender roles in a homosexual relationship: Mav might be the alpha in the sky, but he’s the bitch on terra firma.

It seems like easy pickings to accuse recruitment propaganda of being queer as a kipper, but look at the acres of beefcake on full display in the topless volleyball sequence, little Tom in his painted-on jeans and Rick Rossovich (“Slider”), as Ice Man’s boyfriend, striking a pose showing off his tanned obliques and oiled pecs. (It’s such a perfectly crafted piece of pop art that you should expect to see it screening next to Warhol’s soup can in some idealized MOMA exhibit somewhere down the apocalyptic highway.) Seriously: Who the fuck is this movie for? Then there’s the moment where a fight almost breaks out in a shower room, presaging the naked insect-royale of Eastern Promises by two decades. And yet, apocryphal tales tell of how this film swelled Navy battlements with fresh meat the same way that Backdraft stocked firehouse barracks and 300 stocked Turkish baths–which only supports the pop-psych analysis that pre-actualized teenage boys are the most homosexual beings in existence: Ganymede in retrograde. (Starship Troopers is just looking smarter and smarter.) The real appeal of Top Gun in hindsight isn’t that it’s worth a shit, but that it’s unusually honest about how and why certain entertainments flourish when the key demographic buying tickets consists of young men out of school for the summer, going in packs to the cineplex in jovial bonhomie and brotherhood to experience mute justification of their girl-free lifestyle. Suddenly, the choice to tab director Tony Scott for the picture on the basis of his lesbian vampire opus The Hunger makes a lot of sense. If we can reach a consensus that Top Gun is a gay film, does that, by its nature, mean that it sucks? Of course not. Top Gun sucks because it’s awful.

Gay vampire opus The Lost Boys, on the other hand, helmed by another facile visual stylist in Joel Schumacher, actually has a couple of moments that ring true in the adolescent sweepstakes largely thanks to a too-good-for-this-film performance by Jason Patric. Essentially the mainstream version of Kathryn Bigelow’s concurrent Near Dark (with even the dialogue from hero everyman Michael (Patric) upon meeting his waifish ladylove Star (Jami Gertz) nigh identical to the courting of Mae (Jenny Wright) by Caleb (Adrian Pasdar) in Near Dark), The Lost Boys is also about a good-looking dolt who falls in with a mysterious lovely some summer night only to find that he’s become half-vampire, pulled to the breast of a band of full vampires and urged to officially join the legions of the night by making his first kill. Both feature vampire children fostered by the girl (though only Near Dark does the right thing by burning the little shit alive); both indulge in ’80s drug paranoia; and both contain a happy epilogue wherein the plague is cured and order is restored along nuclear lines with the aid of the “normal” family. Yet where Near Dark speaks of a surrogate family appearing in the doldrums of late adolescence, The Lost Boys, until the very end, speaks of juvenile delinquency erupting in the margins of a broken home. So while The Lost Boys is slick (Michael Chapman’s cinematography is gorgeous), Near Dark is haunted–the one a classic of reassurance (pot-smoking hippie Grandpa (Barnard Hughes) knew about it all along, don’t you worry), the other a classic of moods that captures any twilight in the ’80s, not to mention the uncertainty of the images perpetuated in our culture about that alleged fountain of youth, mass consumerism. It’s an idea that hasn’t completely gone out of style: The American Dream has a lot to do with what you can buy–consider, after all, what President Dubya implored the briefly-united States of America to do after 9/11. Not create a Manhattan Project for renewable, alternative energy, but go to the mall and buy something.

It’s pointed to me that much of the early dialogue in The Lost Boys concerns needing to secure a job in the cozy bayside town of Santa Carla, to which hero Michael, his baby brother Sam (Corey Haim), and their mother Lucy (Dianne Wiest, fresh off her Oscar for Hannah and Her Sisters) have fled following an acrimonious divorce. (Near Dark‘s Caleb is, too, the product of a single-parent home–that one missing a mother in the more traditional fairytale construction.) The focus on the importance of establishing a baseline of employment–with a key reveal occurring in the video store owned by head vampire Max (Edward Herrmann)–speaks as eloquently of the time of its birth as its inevitable drug parable, articulated in a head-sequence in the “cool vampire kids” mine-shaft hangout that has Michael peer-pressured into drinking some serious shit and dissolving (with an assist from editor Robert Brown) into a poster of the Lizard King himself, Jim Morrison. In the end, the picture affirms that the only thing truly important is this image of the older brother with his arm around the younger, echoing a prior transcendent moment when, upon discovering Grandpa’s Norman Bates-ish den of stuffed animals, Michael cracks wise and Sam puts his head in the hollow of big bro’s neck. It’s one of several startling moments of fraternal love in The Lost Boys, each authored by subtle, off-hand reactions to Haim courtesy of Patric that speak to a lifetime of matter-of-fact connection. It’s those moments (and another right before an assault on the vampire cave) that elevate The Lost Boys from the camp ghetto to which the rest of it aspires. (If it’s not Kiefer Sutherland’s ridiculous anti-archangel David and his gang of toothy male models trying to lure Michael to the dark side of underwear modelling and gas fights, it’s Corey Feldman and Jamison Newlander’s abhorrent vampire-fighting Frog Brothers.)

A time-capsule of a film I loved so much as a fourteen-year-old that I and a good friend of mine spent considerable time looking for, and eventually wearing, the silver-framed sunglasses sported by Michael throughout his transformation, The Lost Boys, to my great surprise, hasn’t lost much in terms of impact, though its weight has shifted in the parallax of my middle age. The seduction of Michael doesn’t have the same pull for me as my interest in wearing leather and pretending to want a motorcycle has dwindled, but Wiest’s real fear of losing connection with her children and her desire most of all to find gainful employment, the right friends, and a safe place to live for her kids has accrued a tremendous gravity. Ditto the sibling relationship portrayed by Patric and Haim–something I’ve noticed with my own children, replicated with sensitivity and a surprising intelligence. To the rest of it: Kudos to Schumacher and company for resisting, until the climax, the use of any bluescreen trickery. And were it not for its occasionally obvious desire to be The Goonies with gore, The Lost Boys might’ve been a real classic instead of an artifact that only every now and then justifies the nostalgia people have for it without irony. A shame that Schumacher compares the picture, albeit obliquely, to Some Like It Hot in an attendant DVD commentary…but more on that momentarily.

Released the following year, 1988, Ron Shelton’s fondly-remembered, highly-regarded Bull Durham has aged in ways not so complimentary. What seemed the height of sexual sophistication to a teenager feels talky and forced today–though performances by Kevin Costner (best as a baseball player or a cowboy), Susan Sarandon (best as an aging-slut prototype for Kim Cattrall’s “Sex and the City” character), and Tim Robbins (best as an idiot (savant)) stand up. An especial relief, given that there’s not much that can be done with Shelton’s long, solipsistic, rambling monologues, so pleased with themselves that despite the truly memorable one-liners he drops now and again (“Guys will listen to anything if they think it’s foreplay” is a fave, while “He’s got a million-dollar arm and a five-cent head” penetrated sports-radio vernacular), most of them are buried knuckle-deep in piles of self-pleasuring, onanistic verbiage. Very much the definitive sports film of the Eighties regardless, take it with The Natural (1984) as a nostalgia double-feature that ploughs psychosexual ground similar to Back to the Future (1985)–even if the two moments in which the bull mascot gets devastated by a fastball are all that’s still funny about it. The “church of baseball” speech that opens the picture resonates throughout, reflecting the loneliness and despair of lifetime minor-leaguers pursuing immortality in a child’s game. Alas, there’s too much chatter in the piece, too much posturing by Shelton, too many lazy takes and too much unchecked bloat. I do like that Annie (Sarandon) correctly identifies the hostility Crash (Costner) and Nuke (Robbins) initially have towards one another as latent homosexuality, channelled into mutual loathing. What I don’t like is Costner labouring through his “long, slow, wet kisses” spiel, which reveals exactly how Costner is limited in a film that intends to demonstrate exactly how Costner is gifted.

Bull Durham is midway between Rick Reilly and Shirley MacLaine, a resounding failure punctuated by tiny spurts of genius (Shelton’s superior Cobb is its photo negative) that people speak of with a lot more reverence than it deserves. Still, the moments that are memorable remain so, and if the baseball metaphor is used to better effect in the father/son dynamics of Costner’s subsequent Field of Dreams, the baseball ain’t bad, especially in an extended interior monologue as Crash comes up to bat. As for Costner, his finest films of the decade are probably the 1987 two-fer of The Untouchables and No Way Out–they’re where he honed his Gary Cooper Americana into a finely-tuned, iconic persona: long, tall, a little dim but well-meaning. The best of Costner treats you with respect and awe; bad Costner treats you like you’re somehow stupider than he is. Bull Durham is right when it understands Costner’s BBQ appeal–and horribly wrong when it mistakes him for some sort of speechifying philosopher. Seen as one of his great successes, Bull Durham marks the moment where Costner starts believing himself to be something other than what he is, since it’s the public’s embrace of this film in which he occasionally plays against type that convinced Costner that stuff like The Postman and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves were well within his abilities. To its credit, the picture understands the stupidity of movies like Top Gun: When Bull Durham has the manager (Trey Wilson) tear down his players in the shower room, there’s an understanding that what Annie said earlier about the essential gayness of traditionally masculine pursuits is applicable here. Her request that Nuke wear garters while pitching underscores the gender dynamism at play, for what it’s worth, and the idea of all these pain rituals on the way to maturity (the “big show” as euphemism) takes surprisingly sticky hold in a scene where Crash floods a baseball field, in the company of a character referred to only as “Mr. Hormone” and to the strains of a little Los Lobos. It’s shit, right? But sometimes it’s good shit.

THE DVDsLegend Films dumps another gem from Paramount’s embarrassing catalogue into the disinterested consciousness of pop culture via a completely ordinary 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer that looks exactly like a Nagel painting. Whether by design or unhappy accident, Blue City is stamped by the particular blandness of mid-’80s knock-offs. That said, the presentation is uniform: no sudden bursts of quality, no sudden bursts of shittiness. The accompanying DD 2.0 audio (stereo? Mono? Can’t tell) is a wall of equally modulated noise; a blast of Textones in an early bar scene is horrible, if not as horrible as it would be in 5.1 and not as horrible again as the identical blast of Smithereens in the corresponding bar scene from Bull Durham. I do want to comment on the oft-lauded Ry Cooder score, produced the same year as his genuinely good score for Crossroads–a film directed by Walter Hill as opposed to co-produced and co-written by him somewhere along the production line, and another movie with an affecting appearance by Jami Gertz. The Cooder score for Blue City is not just garbage, it’s fucking garbage. The only thing worse than watching Judd Nelson aimlessly ride a motor-scooter is listening to Ry Cooder sweat bullets to make it seem the slightest bit interesting. Mercifully, there are no special features on the DVD.

Top Gun‘s score by proto-James Horner Harold Faltermeyer, on the other hand, is so terrible that it’s become part of the irony canon of camp-classic macho anthems. You’ll be surprised that you know it–mortified, too. Paramount’s Special Collector’s Edition from 2004 replaces an atrocious first-gen disc with a digital transfer that preserves the film’s projected aspect ratio of 2.35:1 in anamorphic widescreen. It glitters and pops and the little plane models sparkle. For what it’s worth, the many interstitial scenes of Mav riding his motorcycle have that weird Eighties neon patina coined by Michael Mann’s work on “Miami Vice”–and it’s this ineffable quality that dates the thing more quickly than either the chart-topping soundtrack or Kelly McGillis’s giant head’s giant hairdo. Edge-enhancement is at a bare minimum, preserving a lot of the filmic qualities of the period: the grain, a smidge of softness in high-shadow scenes–it all adds to the seediness of it. Like a Mickey Rourke room deodorizer. Or a Francis Bacon painting. Ah, the ’80s. Because this is the ne plus ultra of the blockbuster boom, an accompanying DTS-ES 6.1 remix blows in every positive and pejorative sense of the word. It’s loud, obnoxious, saturated: a wall of noise from beginning to end, lest any of its hambone melodramatics go unnoticed by the stone-deaf.

Appending the film is a terrific patchwork commentary track featuring Scott, Jerry Bruckheimer, co-scribe Jack Epps, real-life Top Gunner Mike Galpin, the film’s technical advisor Pete Pettigrew, and Navy aviator Mike McCabe. The best stuff comes from Pettigrew, who says here and in a supplemental documentary that after a while he gave up on veracity and just did his best to keep Top Gun from “becoming a musical.” Scott expresses his disbelief that he was tabbed for this project on the basis of The Hunger and Bruckheimer expresses an absolute iron-clad knowledge of how to generate a ton of money through facile, homoerotic entertainments that appeal almost exclusively to young men and women in the throes of summer’s doldrums. For people as old as me, there are vintage music videos for Kenny Loggins’s “Danger Zone,” Loverboy‘s “Heaven In Your Eyes,” Berlin’s “Take My Breath Away,” and the aforementioned “Top Gun Anthem,” as well as seven TV spots for the picture. Boy. Boy.

Moving on to the second disc: A long-form, 6-part retrospective, “Danger Zone: The Making of Top Gun” (148 mins.!), is an awe-inspiring thing (no irony intended) that intersperses fresh interviews with B-roll and outtakes. Though Cruise and McGillis are notably absent save through archival footage, recent interviews with Rossovich and Kilmer reveal the chaos of beautiful boys set loose in a beach-side getaway. Kilmer tells of how he got inside Tom’s head with cruel mind games–that coughing “bullshit” as Mav is recapping his escapades was improvised and rattled Cruise–and of how Tom insisted on staying by himself, the “maverick” of yore, across the bay. All betray a strong self-awareness that Top Gun is a hyper-popular piece of shit. Scott, at one point, describes the shooting script as a quarter-inch thick and consisting of the boring spots that bridge the dogfights. The scene in the elevator that Tarantino immortalizes in his aforementioned monologue is revealed to have been a post-production reshoot, McGillis’s masculinizing baseball cap simply a thing they needed to hide that she’d gotten a new haircut for the movie she was working on at the time. Just the same, Scott has a good laugh that the volleyball game was declared the best scene of all time for three years running by prominent gay publication SUCK. Specific sequences are brought up, run through, dissected. The classroom instruction that occurs in a hangar is of particular note for its glaring stupidity. Actor Barry Tubb admits that he put on a cowboy hat therein–a military no-no–as a jab at an ultimately appreciative Scott, who liked how it helped viewers distinguish him from the various other crew-cut white boys. The documentary is a model of how you do them and worth the price of admission by itself. Finishing off the package are storyboards for “Jester’s Dead” and “Flat Spin” with Scott commentary in addition to a fairly exhaustive image gallery and three vintage, immanently-disposable EPKs of a strictly promotional nature: “Behind the Scenes” (7 mins.); “Survival Training” (8 mins.); and “Tom Cruise interviews” (7 mins.).

Similarly loaded is Warner’s Two-Disc Special Edition of The Lost Boys, whose commensurately-scrubbed 16×9 transfer (2.40:1) cleans up most of the Brownian Eighties flecks in the print, though the bonfire concert for The Call is still quite grainy. (But–and this is crucial–not in an unpleasant way.) Black levels are gradual in the night sequences while smoke, fog, all manner of suggestive atmosphere is authored with aplomb; the elegance and understatement of Chapman’s cinematography is faithfully reproduced. (“Join us, Michael” indeed.) A DD 5.1 remix is identical to that of the previous flipper incarnation, which is not to say that it’s bad. In fact, it’s quite good: clean and loud with a clever use of the discretes. Schumacher contributes a film-length yakker in his surprisingly fey way, talking about how he would love to do another vampire movie if only someone would ask him and making me, in a series of synaptic misfires too Byzantine to describe, want to see Flatliners again for the first time in a decade at least. He details his mistake in not having any footage of the bad guys gathering for their final assault (forcing him to improvise a nonsensical reverse shot of an aerial cave penetration) and recalls that the execrable punchline “death by stereo!” in response to a vamp getting blown up by a hi-fi system (what is it with this period and speakers exploding? See also: Back to the Future‘s prologue) was placed after an extended pause to accommodate the reaction of contemporary moviegoers. It’s a reference–oblique, I admit–to Some Like it Hot and the necessity during one post-date drag sequence for Wilder to extend a beat, thus allowing audiences to stop laughing. It’s a connection I drew only because later, Schumacher speaks of how rare it is to stumble upon the perfect exit line. That’s two. That’s not an accident, Joel. And Billy Wilder you ain’t.

Disc Two sports “The Lost Boys: A Retrospective” (23 mins.), a compendium of new-ish interviews with the two Coreys. Feldman looks the same, but as I don’t have cable anymore, I was truly shocked by the weird, alcohol-puffy, alien appearance of Haim. Way too much is made of the genius of the Frog brothers; the revelation that neither Frog knew they were objects of derision and humour as they were shooting (Feldman says he was inspired by Schumacher to study the Rambo flicks for a better understanding of his character) doesn’t speak to me of dedication so much as of eye-rolling, exhausted stupidity. I was interested to hear it confirmed how Patric demanded that he be spared vampire make-up and didn’t speak to Schumacher for some time once it was forced on him in the denouement. Also intriguing that Haim was the one who suggested he ride his bike into the video store to try to enlist Mommy’s help in their campaign. The one anecdote speaks to Patric’s surprisingly affecting performance, the other to how a 13-year-old does, on occasion, know better how a 13-year-old ought to act.

Split into four parts, “Inside the Vampire’s Cave” (18 mins.) sees Schumacher rehashing swaths of his pretty-good commentary. I always enjoy hearing Richard Donner talk, though, and his belief in the film and the idea that its popularity has a lot to do with a successful re-structuring of the vampire mythos as a paranoia piece is what led me to a reconsideration of the picture’s relationship to Near Dark. Leave it to Hermann, meanwhile, to bring up Freud and Jung. And bless his heart for relieving me of that task. A quick revisit to the film’s centrepiece slaughter reminds of the diner sequence from Near Dark–and a middle segment speaks to the sexual element of vampirism. Feldman suggesting that The Lost Boys pioneered vampires as succubae tells me a lot about how deprived Hollywood kids are of a meaningful education. A brief rumination on a possible sequel meanwhile dates the package, as a DTV sequel surfaced this past July. “Vamping Out: The Undead Creations of Greg Cannom” (13 mins.) explores the film’s make-up effects and includes what has to be the ten-millionth time I’ve learned that cosmetic contact lenses are hard and painful. “The Vampire’s Photo Gallery” of Cannom’s creations is inexplicable and interminable. Let’s be honest here: who bothers with this shit? “Haimster & Feldog: The Story of the Two Coreys” (5 mins.) is pretty much what you’d expect from these two yahoos. Am I surprised that there’s a reality show about them? I am not.

A “Multi-Angle Video Commentary” with Haim and Frogs Feldman and Newlander furnishes a couple of scenes from the film with togglable picture-in-picture windows wherein each commentator remembers the glory days, such as they were. That the trio comprises the weakest element of The Lost Boys is something that people more polite than me try not to mention. “The Lost Scenes” (15 mins.) shows more interaction between Patric and Haim that looks, for the life of me, like brothers interacting. I’m sort of amazed, you know, to be discovering that at this juncture. An elision that would’ve established the faulty wiring responsible for the demise of a vamp later on is nice, but I liked more the bit where Patric tells mom Weist that he may want to get a job instead of going to college. Genius. A shot of Michael trailing Star through a carnival crowd was excised, I think, because two of the extras can’t resist staring right into the camera–a shame, because it captures a feeling of youth on a twilit summer that I think is rather brilliant. A crusading director character hits the cutting-room floor with good reason but a sequence with Michael working as a trash collector has a sadness about it that I can’t quite quantify. Funny how these deleted moments have in them, like the movie proper, little shards of truth. The best? Michael trying to work out and then wandering around like Hugh Hefner after a particularly unearthly bender. A close second is an extended love scene almost as icky as the Top Gun tongue-and-grope session. “The World of Vampires” is an interactive-map function that allows one to click on various places on a world map to learn about local legends of undead bloodsucking fiends. Lightly animated and illustrated, it’s fucking fantastic stuff–especially Australia’s “Yarma-Ya-Hoo.” I’m pretty freaked out by “Lamastu” of Mesopotamia: “She Who Erases.” Christ. Lou Gramm‘s ridiculous video for “Lost in the Shadows” brings back a lot of memories (he says, dating himself), as does The Lost Boys‘ own most excellent trailer.

MGM reissues Bull Durham in a Collector’s Edition on the heels of a Special Edition, I guess to properly commemorate the film’s twentieth anniversary. Writer-director Ron Shelton provides a feature-length commentary track that is as verbose as the film it decorates and packed silly with information about the creation of the screenplay, its genesis having a lot to do with Shelton looking for an angle and finding it in casting a woman as the narrator of a baseball flick. That Shelton powers through this thing without taking a breath…somebody call Guinness. He’s a blowhard of the first degree and pretty pleased with himself. Just as this flick is connected to Blue City by proximity and a bad bar scene with bad music, it’s connected to Top Gun by Tim Robbins and to all of them by its latent gayness. Shelton misses no opportunity to congratulate himself on clever turns of phrase, by the way, pausing after he’s quoted himself to allow the actors to quote him in turn. It should be noted, Shelton says, that he listened to Edith Piaf and Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys throughout the writing process. It should be noted, I says, that Shelton is an asshole. Having Annie listen to Piaf’s “Non, je ne regrette rien” in a low moment where she affirms that she has no regrets is the height of empty pomposity. It’s the school of Dean Koontz: the entrance exam is a stethoscope. Apropos of nothing save that I’m a bit of an asshole myself, there’s no explanation, sadly, of why “Sixty Minute Man”–the singers of which Shelton identifies as The Platters when it’s The Dominoes–isn’t included on the film’s soundtrack.

Costner and Robbins team up for a second yakker with considerably less self-consciousness and arrogance. Costner has the good grace to thank the four heads of long-defunct Orion for having the courage to finance unusual pictures–and it’s that kind of unaffected, everyday-guy quality that fuels Costner’s mystique. I love that Robbins raises the issue of whether or not Pete Rose should be in the Hall, and when Costner gives props to Sarandon for flying herself to Shelton and auditioning for the role she eventually won, it rings with genuine admiration. Here it is: I love Costner. For his part, Robbins discusses the beginnings of his offscreen relationship with Sarandon. It’s incredibly sweet. I mean it. All of it has a chumminess and unforced camaraderie and it’s indispensable in the manner of those Carpenter/Russell tracks–or the Raimi/Campbells. How do they handle the sex scene? They giggle. Bless their hearts, what else can you do? I like, too, that Costner sort of changes the subject by noting that they switched cinematographers mid-scene. He’s a gentleman, man, I’m serious about this guy. Just don’t ever cast him as a PhD again. Costner and Robbins also take opportunities to quiz one another about film craft, their respective directorial careers, and the like. It’s really just fucking awesome. Both commentaries decorate a best-yet 1.85:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer that shows a lot of grain, but in a good way–in that good way. The DD 5.1 audio is serviceable for what amounts to a dialogue-driven pic.

“The Greatest Show on Dirt” (19 mins.) essays the Minor League circuit, with Shelton boasting that he alone shone a light on it for elite MLB fandom. Whatever it starts out as, it ends up being an at-times-verbatim rehash of Shelton’s yak-track, except now instead of watching the film as he regales us with the story of his writing Bull Durham‘s script in one sitting without an outline, we get to watch him as he tells it. “Diamonds in the Rough” (15 mins.) is a mini-doc on the history of the Minor League game, while “Between the Lines: The Making of” (29 mins.) has even more of Shelton (from 2001) waxing quixotic about his time in the minor leagues and how he wrote the script in one sitting without an outline. Lots of Durham Bulls executives are interviewed and encouraged to elevate Shelton to the sainthood to which he has nominated himself. Robbins, Costner, and Sarandon contribute some nice reflections and it all washes out exactly the same way that the warring commentaries do: arrogance vs. humility. I learned more facts from the former; I understood better the picture’s success from the latter. A period “Kevin Costner Profile” (2 mins.) is a low-rent, lo-fi pre-“Biography” bio with purple narration and Costner showing a lot less of the humility in 1988 that makes him so likeable twenty years on. It’s a peek at the Costner who would shit away his appeal before recovering it at the bottom. “Sports Wrap” (3 mins.) is a faux-promo spot that acts as an extended, dreadful trailer for Bull Durham. It rounds out the platter.

THE BLU-RAY DISC – TOP GUN

by Bill Chambers Paramount consolidates their double-decker Special Collector’s Edition DVD of Top Gun onto a single Blu-ray Disc that’s an improvement in every way on its standard-def counterpart. Nevertheless, the 2.35:1, 1080p presentation of the film itself has its share of peccadilloes, from the heavy black crush that asserts itself whenever we see inside a cockpit to the sometimes-frozen appearance of grain (which, along with some occasional banding, suggests they ought to have spread this release over two platters as well to decrease the need for compression). Every so often, edge-enhancement rears its head as if to compensate for the definition lost to Tony Scott’s indefatigable smoke machines, a totally egregious gesture in HiDef. On the bright side, colours are astonishingly vibrant and free of bleed, there’s newfound depth to the image, and small-object detail often impresses. As for the sound, while I was forced to listen to a 5.1 downmix of both the Dolby TrueHD and 6.1 DTS Master Audio tracks, there’s no doubt in my mind that an A/B comparison on higher-end equipment would only confirm the superiority of the DTS option. Even after making it a fair fight by matching their volume levels, the DTS is a much more intense experience–also more dynamic, more transparent, and, especially where the songs are concerned, more articulate. (For better or worse, Kenny Loggins and Berlin sound comparatively muted in the DTHD alternative.) Overall, if you’re a Top Gun aficionado or a collector of high-end gay porn, it’s worth the upgrade, but be forewarned that every attempt to play the standalone featurettes–including the exclusive-to-BD “Best of the Best: Inside the Real Top Gun”–bounced me back to the main menu on my Sony BDP-S300. (Time to upgrade that firmware again, I suppose.) The remaining documentary footage is enhanced for 16×9 displays but has not been upgraded to HD.

- Blue City

83 minutes; R; 1.78:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 2.0 (Stereo); CC; DVD-5; Region One; Legend - Top Gun

109 minutes; PG-13; 2.35:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1, English DTS-ES 6.1, English Dolby Surround, French Dolby Surround; CC; English, Spanish subtitles; 2 DVD-9s; Region One; Paramount

- The Lost Boys

97 minutes; R; 2.37:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1, French DD 1.0; CC; English, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-9 + DVD-5; Region One; Warner

- Bull Durham

108 minutes; R; 1.85:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1, French DD 2.0 (Mono), Spanish Dolby Surround; CC; English, Spanish subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; MGM - Top Gun (BD)

109 minutes; PG-13; 2.35:1 (1080p/MPEG-4); English 5.1 Dolby TrueHD, English 6.1 DTS-HD MA, French DD 5.1, Spanish DD 5.1; English, English SDH, French, Spanish, Portuguese subtitles; BD-50; Region-free; Paramount

![Top Gun [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51yRbd0KHvL._SL500_.jpg)