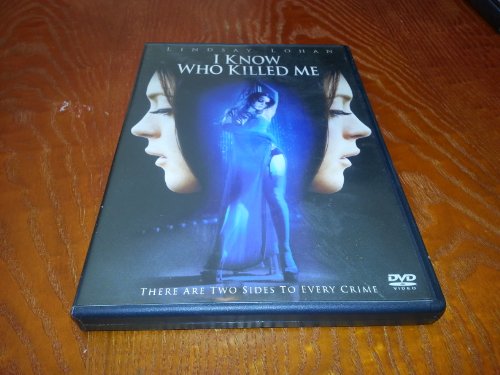

I KNOW WHO KILLED ME

**½/**** Image A- Sound A- Extras D

starring Lindsay Lohan, Julia Ormond, Neal McDonough, Brian Geraghty

screenplay by Jeffrey Hammond

directed by Chris Sivertson

CAPTIVITY

*/**** Image B+ Sound A Extras C

starring Elisha Cuthbert, Daniel Gilles, Michael Harney, Pruitt Taylor Vince

screenplay by Larry Cohen and Joseph Tura

directed by Roland Joffe

by Alex Jackson SPOILER WARNING IN EFFECT. I wasn’t that upset about the bad reputation I Know Who Killed Me had acquired until I saw Roland Joffe’s Captivity. I Know Who Killed Me recently took home Worst Actress and Worst Picture Razzie awards and was at one point listed on WIKIPEDIA as “one of the worst films ever made.” Captivity, meanwhile, despite the not-insignificant controversy surrounding a disastrous billboard campaign and a scathing editorial by Joss Whedon condemning it sight-unseen, has all but vanished into obscurity. I guess that makes a certain amount of sense. Poor Lindsay Lohan (I’m sorry, but her pathetic Marilyn Monroe spread in the current issue of NEW YORK gets my sympathy sensors buzzing) is a staple of the tabloid industry and an easy target for hipster schadenfreude. I Know Who Killed Me has the trappings of a serious thriller and requires Lohan to do a little bit of stretching while playing off her off-screen persona. Captivity, on the other hand, is considerably less ambitious and considerably more exploitive, and as such, actress Elisha Cuthbert’s participation can be dismissed as just another former TV star paying her dues in the horror genre.

by Alex Jackson SPOILER WARNING IN EFFECT. I wasn’t that upset about the bad reputation I Know Who Killed Me had acquired until I saw Roland Joffe’s Captivity. I Know Who Killed Me recently took home Worst Actress and Worst Picture Razzie awards and was at one point listed on WIKIPEDIA as “one of the worst films ever made.” Captivity, meanwhile, despite the not-insignificant controversy surrounding a disastrous billboard campaign and a scathing editorial by Joss Whedon condemning it sight-unseen, has all but vanished into obscurity. I guess that makes a certain amount of sense. Poor Lindsay Lohan (I’m sorry, but her pathetic Marilyn Monroe spread in the current issue of NEW YORK gets my sympathy sensors buzzing) is a staple of the tabloid industry and an easy target for hipster schadenfreude. I Know Who Killed Me has the trappings of a serious thriller and requires Lohan to do a little bit of stretching while playing off her off-screen persona. Captivity, on the other hand, is considerably less ambitious and considerably more exploitive, and as such, actress Elisha Cuthbert’s participation can be dismissed as just another former TV star paying her dues in the horror genre.

I first saw I Know Who Killed Me at the drive-in last summer. It was the bottom half of a horror-themed double-feature headlined by Rob Zombie’s Halloween remake. This is just about the perfect environment in which to see I Know Who Killed Me. My standards were low, not only because the film’s reputation was pitiable, but also because it wasn’t even the movie I’d come to see. I went for Halloween and stayed because I got two movies for the price of one. And with summer (and drive-in) season winding down, I was feeling kind of…nostalgic, I guess it is. Not nostalgic for my own adolescence specifically, but for the idea of adolescence, perhaps.

The opening sequence of I Know Who Killed Me is really fantastic. Scored to Vietnam‘s “Step On Inside” (with its relevant lyrics “And the tv’s sayin’ somethin’ but i never notice what it says/’cause i’m drifting through a dream, it seems the witch doctor’s stole the bed”), it features Lindsay Lohan stripping for a bar full of bikers. The title comes up the moment she makes her entrance, nervously scanning the room, apprehensive about walking out on stage. She works up the nerve to go through with it and doesn’t look back. Lohan’s striptease is slow and seductive. Rather than consciously performing for the men, she seems to be under hypnosis. The focus of the camera goes in and out, and shortly after she finishes dancing she’s bathed in a red light that almost completely obscures her. The last image of the sequence is a close-up of her hand bleeding as it slides down the stripper pole. We intuit that by going on stage and stripping, she has chosen “death” and found peace and transcendence in it.

In the comments section of our blog, the great Dave Gibson (under the unregistered moniker “Dave G”; I think that was him, anyway) called I Know Who Killed Me the “Best Grindhouse Movie” of the year and Grindhouse the worst. The comment struck me as needlessly contrarian at the time (I love Grindhouse so much I want to have babies with it), but comparing this strip-club prologue to the one in Grindhouse‘s Planet Terror, I can see his point. This striptease isn’t exploitive and it isn’t at all ironic or hyperbolic about the cinema of exploitation. It treats this “grindhouse” convention with heart and finds the poetry between the lines.

Audrey Fleming (Lindsay Lohan) is a popular and well-liked teenager living a comfortable upper-middle-class existence in the suburb of New Salem. A serial killer who amputates his victims’ limbs before leaving them to die kidnaps her. Audrey survives the attack, but when she wakes up she claims to be Dakota Moss, an exotic dancer who grew up the daughter of a crack-addicted mother. Dakota doesn’t know anything about this “Aubrey chick,” but she has the same exact wounds as the previous victims. Aubrey’s friends and family, as well as the FBI, think Dakota is a delusional personality whom Aubrey has adopted as a coping mechanism. Dakota arrives at a considerably stranger conclusion: She believes that she and Aubrey are identical twins separated at birth who share a telepathic connection whereby Dakota literally experiences trauma as Aubrey experiences it.

So who’s right? Since the film is told almost entirely from Aubrey/Dakota’s perspective, it would appear we’re meant to believe her version the first time around (probably the principal source for the hatred the film has received). On subsequent viewings, however, we begin to agree with the FBI that this whole Dakota thing is a delusion. Or at least that you can say Dakota Moss doesn’t actually exist and there is only Aubrey. We know early on that Aubrey had created a stripper character called Dakota, and this is what contextualizes the opening scene. Later, when we see Dakota and Aubrey sharing the same physical space, we dismiss this key piece of evidence as part of the “twin connection.”

What clenches the “delusion” theory is the abundance of blue throughout the film. We realize on a second go-round that director Chris Sivertson has been hitting us over the head with it. Most significantly, the killer cuts up his victims with a piece of blue glass and early in the film Aubrey receives a blue rose from her boyfriend. But the colour pops up constantly throughout the film, on the wallpaper in Aubrey’s bedroom as well as on her computer, on her pens and folders, in the ink she uses to write her Post-It notes, on the candy dish in the Fleming household, on the sheets and scrubs in the hospital, at the bus stop Dakota goes to after work, in the stripe on the bus that picks her up, et cetera et cetera et cetera.

At the end of the film, Dakota discovers Aubrey buried in a blue glass coffin. This could mean that Aubrey “thought blue” and sent these thoughts to Dakota so she could be saved. Indeed, the clue that helps Dakota figure out who “killed” her and find Aubrey is a blue ribbon. Or it could mean that Aubrey is dying and has created this fantasy of an identical twin named Dakota Moss to save her–the flashes of blue could simply be instances of the fantasy decaying in her oxygen-deprived brain. This latter explanation better matches our data. The blue motif is extended to the glass weapon and the killer’s shirt, long after it has served its purpose. And, of course, the motif calls attention to itself–there’s an unreality to it that manages to justify and explain this ridiculous plot.

The fatal flaw of the film is in providing a motivation for the serial killer divorced from sex. The dismemberment of his victims isn’t sexualized, there’s another purpose to it. If Aubrey were a victim of rape, we could see her creating the Dakota persona–a foul-mouthed, highly sexual exotic dancer from the wrong side of the tracks–accordingly: adopting the “whore” archetype would be a way to reclaim the sexuality that was taken from her. Then the idea of her finally choosing death in the form of sexual exploitation in that terrific first scene would gain a little poignancy, à la Pandora’s Box or Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. This would only be compounded by Lohan’s own baggage. Her first film was the 1998 remake of The Parent Trap, also about separated identical twins; and seeing it perverted in this film, with Lohan now playing a one-legged promiscuous party girl rife with elements of self-parody, would only add to the pathos.

She wasn’t raped, though, and so the twinning of Aubrey and Dakota is more a metaphysical question than a psychological one. In a way, the film feels very superficial, a bit too much like a crossword puzzle you discard as soon as you’ve solved it. As there is no longer any reason for Lohan to play a stripper, I Know Who Killed Me becomes a ripe target for cheap shots, and lines like “Hospitals are for poor people” or “People get cut. That’s life” never evolve beyond camp. The film had a shot at greatness, it just never pulled the trigger. The only explanation for the failure is cowardice–a fear of addressing sexual violence in a pop context. For this reason, I Know Who Killed Me is a spectacularly frustrating misfire.

As I said, I didn’t start feeling defensive about the film until I saw Roland Joffe’s Captivity. I have to admit that I couldn’t believe my eyes when I initially read the film’s basic premise. A famous supermodel, played by Elisha Cuthbert (better known as the obnoxious Kim Bauer from “24”), is kidnapped and tortured by mysterious strangers; it sounded like somebody had finally adapted Gary Roberts’s “Starfuckers” series for the big screen. Alas, believe it or not, Elisha Cuthbert is not raped, either, and there aren’t any real sexual overtones to her humiliation. Yet she is still a sexually unavailable supermodel, she is still kidnapped, and she is still tortured. And the film is still not much more than us watching her being tortured. What we have here, then, is a misogynistic movie that misogynists are going to find disappointing. I’m reminded of Roger Ebert’s account of watching a censored version of I Spit On Your Grave, a movie he doubly hated in its censored version: “The movie was beneath contempt in the first place. But for exhibitors to hold it over on the basis of its reputation for nauseating violence–and then to show a censored version without that violence–is a species of doublethink too diseased for me to penetrate.”

Cuthbert is force-fed some body parts blended into a slurry and later must choose whether to off her dog or allow herself to die. She chooses to kill the mutt, who promptly explodes in a mess of greasy grimy doggie guts. It’s extremely primitive stuff. Wasn’t it George Lucas who said it’s easy to get a reaction from the audience, just kill a dog? In its violation of the typical standards of good taste, Captivity isn’t asking its audience to do anything more than instinctively cringe. Joffe and his screenwriters, Joseph Tura and famed B-movie auteur Larry Cohen, don’t seem to have much interest in actually exploring how far they can push their audience’s moral limits, much less what makes these torturers tick. The hint of an incestuous attraction between a fat older man and his younger brother is especially disappointing: the thread is so underdeveloped that it’s reduced to just another gross-out effect. Captivity‘s gratuitousness is such that I became nostalgic for the Saw pictures, of which this film is obviously derivative. At least they’re ambitiously pretentious.

Trying to acknowledge the sexual connotations of the kidnapping without showing her getting violated, the filmmakers reach a compromise. The whole torture scenario proves to be a ruse to soften her up for seduction. (The film is tagged “rape by deception” on the IMDb.) Of course, once her kidnappers grow bored with her, they’ll kill her. Not that any of this plausible, but it sets the stage for the reversal, where Cuthbert discovers what’s happening and gains the upper hand, emasculating and killing her captors. It’s at this point that the film flips from misogynistic to faux-feminist. The key moment is when she shoots out a window covered by one of her advertising shoots. Her captors were videotaping every step of her ordeal, and here the film draws a direct line between her life as torture victim and her life as a supermodel. What these men have done to her is merely an extension of what men have been doing to her all along. By destroying this constructed image of herself, she is presumably overthrowing the oppressive shackles of the Male Gaze. Fight the power, sister!

After seeing Captivity, I found I Know Who Killed Me all the more impressive in the way it offers a relatively complex take on the iconology of gender while successfully avoiding categorization as either misogynistic or misandrist. (Eli Roth’s Hostel Part II looks even more impressive, locating an honestly cynical thread of misanthropy in the turnaround from rape to castration.) Captivity is comparatively thoughtless. This is the first “torture porn” film I’ve seen where the woman’s revenge truly felt like a rationalization for the sexualized violence preceding it. I was particularly offended by a discussion in the film’s final scene, via an interview played in voiceover, in which a journalist asks Cuthbert if she feels vigilante justice is morally justified. Who do they think they’re kidding? Could anybody seeing this film not take her side?

I Know Who Killed Me widescreen vs. fullscreen (inset)

THE DVDs

Sony Pictures brings I Know Who Killed Me to DVD in widescreen and fullscreen presentations on the same side of a dual-layer platter. Been a while since I saw one of these; I guess full-frame isn’t quite obsolete yet. The 2.42:1, 16×9-enhanced transfer retains most of the potency of the film’s hyperkinetic colour scheme (in addition to preserving I Know Who Killed Me‘s ‘scope dimensions) and is matched by driving, nicely-balanced Dolby Digital 5.1 audio. A/V quality shows a little strain near the climactic battle, but the compression is generally smooth, perhaps owing to the film’s HD origins. Extras are pretty much worthless, reminding of Mike Nichols’s explanation as to why he’ll never brandish the deleted scenes from any of his films. (“It’s like when you’ve written something, when you cut a paragraph, doesn’t it seem dead to you? Doesn’t it look like something you’d never want to include, because the point is, it could go?”) An 81-second “Alternate Opening” simply adds a couple more shots of the pond outside the strip club, while the one-minute “Alternate Ending” is a variation on the old “it was all a dream” routine. “Extended Strip Dance” (6 mins.) is what it is. Finally, we have three minutes’ worth of mildly amusing bloopers. Rounding out the disc are forced trailers for Superbad, Resident Evil: Extinction, and the Blu-ray technology plus optional ones for The Brothers Solomon, Spider-Man 3, and Hostel Part II.

Lionsgate’s DVD release of Captivity doesn’t fare much better. The 2.42:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer starts off brilliantly (check out the red in Cuthbert’s lipstick!) but too often looks dupey and digitized. I suspect that’s because the footage reinstated to qualify this as “uncut” was not sourced from a print but rather dumped off an Avid workstation (or something like it). Whatever the case, it lends the film a strange stop-start rhythm. DTS-ES 6.1 and Dolby Digital 5.1 EX listening options are included, and while both are loud, sharp, and fitfully spine-tingling, it’s immediately apparent that the DTS track has the edge from the pre-credits thwack! of a sledgehammer. Extras begin with “The Making of Captivity” (11 mins.), a fairly standard (if spoiler-heavy) making-of featurette that depressingly shows the once-esteemed Joffe earnestly explaining his process and what Captivity means to him. “On the Set of Captivity” (15 mins.) consists of dull B-roll elucidating how shots like the acid deformation and the body part force-feeding were executed. Six deleted scenes collectively running 15 minutes aren’t any more or less gratuitous than what ended up in the film. Highlights: a bizarre subplot playing on the Cuthbert character’s fear of vultures and two alternate endings, the first downplaying the film’s “grrl power” uplift, the second virtually eliminating it. Forced trailers for the “Movies To Die For” series, H.P. Lovecraft’s The Tomb, The Mummy Maniac, and Saw III (the first three preceded by the red “Restricted Audience” banner from the MPAA) and an optional one for Captivity round out the platter.

- I Know Who Killed Me

106 minutes; R; 2.42:1 (16×9-enhanced), 1.33:1; English DD 5.1, French DD 5.1; CC; English, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; Sony - Captivity

85 minutes; Unrated; 2.42:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1 EX, French DTS-ES 6.1; CC; English, Spanish subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; Lionsgate/Maple