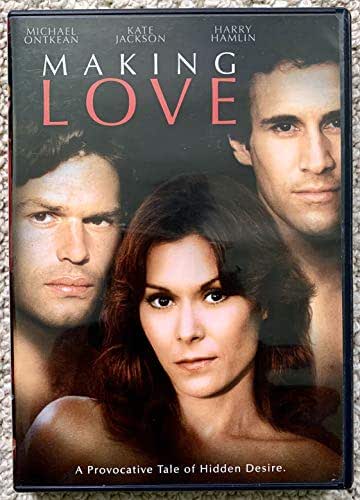

*/**** Image B+ Sound B+

starring Michael Ontkean, Kate Jackson, Harry Hamlin, Wendy Hiller

screenplay by Barry Sandler

directed by Arthur Hiller

by Travis Mackenzie Hoover It's regrettably easy to mock Arthur Hiller's Making Love from a contemporary vantage point. Made long before the queer revolution of the early '90s (but not long after Cruising, its evil opposite number), the film is at once brave and cowardly, daring to utter the word "gay" while refusing to say it in a context where it might actually mean something. So much effort has been expended to be "tasteful," "mature," and "adult" that the filmmakers take out any real threat to the status quo–Making Love is contained to the kind of dull bourgeoisies as far removed from the front lines as possible. The comedy lies in watching these sitcom creations try to enunciate ideas that are entirely beyond their ken, speaking the name of the love but not the particulars that might quicken the blood.

"He had this stack of Gilbert and Sullivan records," observes Claire (Kate Jackson) in the opening line of the film, and Making Love never recovers. What proceeds is a series of alternating close-ups in which Claire and writer-type Bart (Harry Hamlin) discuss the one who got away; through the cheesy "restraint" of the neutral white background and the ham-fistedness of the dialogue, we ascertain that they're both referring to Zack (Michael Ontkean), husband of the former and lover of the latter. Problem is, they talk in such hushed tones that we're cued for a love god. What we wind up with is the same tweedy jerk familiar from a million Ordinary People knockoffs. He's so bland that he barely registers as human, but this doesn't stop anyone from speaking of him as though he were St. Francis of Assisi.

The destruction of a marriage, then, is reported in agonizing, enamel-white detail. Bart walks into Zack's doctor's office and sweeps him off his feet; Claire watches as her marriage to a nifty husband slips through her fingers. Zack sits around with Bart in the latter's astonishingly banal pad and discusses personal issues, while Claire sits in her even uglier home and wonders where it all went wrong. But despite one kiss, a little bit of Hamlin beefcake, and a brief discussion of staying true to yourself, gayness on its own doesn't make much of a dent. The film's insistence on being a "talk" movie–in which people refer to things but are never seen doing them–is an example of how Making Love hedges its bets but refuses to play ball with the subject matter.

Of course, it might help if the creative personnel weren't high on nitrous oxide and acting like David Lynch without irony. Faith in the already-unimaginative structure (cribbed without comprehension from Sunday Bloody Sunday) is destroyed completely by the near-surreal dialogue, which gives the impression that the writers were sequestered from any contact with the outside world beyond what they could glean from watching television. When asked if he was athletic as a kid, Zack responds, "The most I did was jump to conclusions!" You'd groan if you hadn't been groaning through the last 90 howlers that screenwriter Barry Sandler threw at you. It's like the whole thing had to be separated from mainstream life, and Sandler does his part by inventing emotions and exchanges that nobody would ever say.

The film brings to mind the radical-left criticism that equal marriage asks for inclusion in the very institutional order that has oppressed homosexuals for so long. Making Love makes a big show of its good heart in finally absorbing gay issues into a mainstream film, but that relentless mainstreamness is more for bragging rights than for reorienting Hollywood's policy of horror at, or invisibility for, gays and lesbians. It's for straights who want to be seen as liberal without actually giving up representational ground–who want to command instead of being written upon. The irony is that it's likely more interesting now than it was in 1982. It's a bizarre artifact produced under the most misguided of circumstances and contorted in outrageous ways, and so it's fascinating for reasons that supersede mere cinema.

THE DVDFox's DVD presentation of Making Love is merely adequate. There's a distinct fuzziness that bedevils the 1.85:1, 16×9-enhanced image, with some oversaturation problems to boot (probably compensating for the typically mute '80s palette), but it's mostly tolerable. The Dolby 2.0 stereo sound is similarly soft, though that perhaps befits a film trying to be as non-abrasive as possible. The only extras are the film's hilariously evasive trailer plus trailers for The Object of My Affection, The Dreamers, and Next Stop, Greenwich Village.

111 minutes; R; 1.85:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 2.0 (Stereo), English DD 2.0 (Mono), French DD 2.0 (Mono), Spanish DD 2.0 (Mono); CC; English, Spanish subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; Fox

![Dirty Harry [Ultimate Collector's Edition] - Blu-ray Disc FFC Must-Own](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/6a0168ea36d6b2970c016304cd768d970d-600wi.gif?resize=100%2C91&ssl=1)

![The Shining (1980) [2-Disc Special Edition] - DVD shining](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/shining.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)