SCUM (BBC VERSION) (1977)

***½/****

starring Ray Winstone, Phil Daniels, David Threfall

screenplay by Roy Minton

directed by Alan Clarke

SCUM (THEATRICAL VERSION) (1979)

***½/****

starring Ray Winstone, Phil Daniels, Mick Ford

screenplay by Roy Minton

directed by Alan Clarke

MADE IN BRITAIN (1982)

***½/****

starring Tim Roth, Eric Richard, Terry Richards

screenplay by David Leland

directed by Alan Clarke

THE FIRM (1989)

***/****

starring Gary Oldman, Lesley Manville, Phillip Davis

screenplay by Al Hunter

directed by Alan Clarke

ELEPHANT (1989)

***½/****

screenplay by Bernard MacLaverty

directed by Alan Clarke

DIRECTOR: ALAN CLARKE (1991)

**/****

directed by Corin Campbell-Hill

by Travis Mackenzie Hoover What would Andre Bazin have made of Alan Clarke? Both the thinker and the maker were committed to capturing something real, the one stoked on Italian neo-realism and the verity of deep-focus long takes, the other brilliantly deploying montage and the Steadicam. But where Bazin was a passive sort of theorist, Clarke was all about rubbing your face in the action, his efforts to conceal his method of brutal madness to the contrary. He single-handedly redeemed the often stuffy and half-considered mode of British social realism, wiping clean the condescending memory of Richardson, Reisz, and early Lindsay Anderson and even eclipsing old reliable Ken Loach in his commitment to a version of reality. Clarke rescued the genre from high-mindedness and shoved it into your gut like something built from scratch in the borstal hell of his Scum.

by Travis Mackenzie Hoover What would Andre Bazin have made of Alan Clarke? Both the thinker and the maker were committed to capturing something real, the one stoked on Italian neo-realism and the verity of deep-focus long takes, the other brilliantly deploying montage and the Steadicam. But where Bazin was a passive sort of theorist, Clarke was all about rubbing your face in the action, his efforts to conceal his method of brutal madness to the contrary. He single-handedly redeemed the often stuffy and half-considered mode of British social realism, wiping clean the condescending memory of Richardson, Reisz, and early Lindsay Anderson and even eclipsing old reliable Ken Loach in his commitment to a version of reality. Clarke rescued the genre from high-mindedness and shoved it into your gut like something built from scratch in the borstal hell of his Scum.

Clarke proved to be the greatest British director since Hitchcock or Powell and Pressburger, and though Terence Davies would later seriously challenge him for the title, there’s no denying Clarke’s singular achievement in a mode often turned over to self-important crusaders. While the likes of Frears, Kureshi, et al would do excellent work in the same style, there are trace elements of career-building or stylistic digression that take the realist mode lightly enough for questioning. Not so Clarke, a filmmaker utterly determined to suffocate you in the empty spaces between words that are often omitted for editorializing or visual flourish. He was as brutally manipulative as Hitchcock and as unabashedly physical as the Archers, but he was unconcerned with taking credit for his style and thus turned you over to the nightmare instead of his own feelings on that nightmare.

Which is not to say he didn’t identify with the ego. His heroes are generally bloody-minded bastards determined to stay at the top of the heap despite absurd conditioning and insurmountable odds. Carlin in Scum rises to the head of the borstal class through a combination of violence and charisma, keeping his head above water in a place determined to brutalize him for stealing thirty bob worth of scrap. Skinhead Trevor in Made in Britain embodies everything polite society despises in an attempt to salvage his sense of self from a life on the dole and the prospect of no future in England’s big dreams. And amoral Bex in The Firm rages against his own boredom by raging against other soccer hooligans, essentially conditioning himself to the conclusion to which the Thatcher system would condition others. None of them is blameless, but none of them can be written off as aberrations, either.

Which is not to say he didn’t identify with the ego. His heroes are generally bloody-minded bastards determined to stay at the top of the heap despite absurd conditioning and insurmountable odds. Carlin in Scum rises to the head of the borstal class through a combination of violence and charisma, keeping his head above water in a place determined to brutalize him for stealing thirty bob worth of scrap. Skinhead Trevor in Made in Britain embodies everything polite society despises in an attempt to salvage his sense of self from a life on the dole and the prospect of no future in England’s big dreams. And amoral Bex in The Firm rages against his own boredom by raging against other soccer hooligans, essentially conditioning himself to the conclusion to which the Thatcher system would condition others. None of them is blameless, but none of them can be written off as aberrations, either.

Favouring nurture over nature, Clarke was determined to establish the environment as the crucial factor in the making of a man. The borstal in either version of Scum, the social work system of Made in Britain, and the macho head-slamming intimidation scheme of The Firm all create the monsters needed to justify their machinations. The director never allows you to stand outside the action and observe–he tosses you into the world of pain and asks you to consider what you’d do under these circumstances. This reaches an apotheosis in Elephant, where environment is everything: public executions happen without a clue as to why, but the implications of living with constant death in Northern Ireland are crystal clear. Brechtians will have no truck with Clarke; he’s so closed in on the action that you can’t help but feel the protagonist’s agony.

Although he’d never let on, Clarke was a formal powerhouse, constantly centred on surrounding space and, with the introduction of the Steadicam, perpetual motion. The two incarnations of Scum brilliantly employ montage in a final sequence where “screws” are separated from inmates by a divide that will never be crossed; the feature film, meanwhile, uses its hospital-white walls as blank emptiness determined to blanket everyone trapped inside. And once Clarke’s camera was free to roam, so were his characters, who chafed under physical restraint. Made in Britain is masterful at depicting a young man pushing the motive limits of the economy that confines him, while Elephant becomes Wavelength with carnage, leaving in the “irrelevant” lead-up so that we might appreciate the dead air that refuses to comment on unspeakable acts.

Although he’d never let on, Clarke was a formal powerhouse, constantly centred on surrounding space and, with the introduction of the Steadicam, perpetual motion. The two incarnations of Scum brilliantly employ montage in a final sequence where “screws” are separated from inmates by a divide that will never be crossed; the feature film, meanwhile, uses its hospital-white walls as blank emptiness determined to blanket everyone trapped inside. And once Clarke’s camera was free to roam, so were his characters, who chafed under physical restraint. Made in Britain is masterful at depicting a young man pushing the motive limits of the economy that confines him, while Elephant becomes Wavelength with carnage, leaving in the “irrelevant” lead-up so that we might appreciate the dead air that refuses to comment on unspeakable acts.

In his relentless exploration of the polite society’s fringes, he immediately calls to mind that other restless social-minded depressive, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Both men sought to uncover the mechanism behind oppression, finding it in the personal sphere; both routinely depicted society’s attempts to program out difference or otherwise cast off those who fail to make the social grade, whether they deserve to or not. But while Fassbinder often succumbed to Walter Benjamin’s “left-wing melancholy,” Clarke was not about to let matters drop. His films are of inverted optimism, hoping against hope that something might come of their revelations–something like the collapse of the building that houses the Thatcher nightmare.

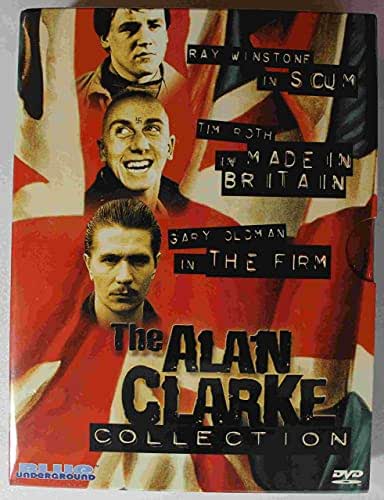

I do have quibbles with Blue Underground’s “The Alan Clarke Collection”, soon to go out of print (though single-disc issues of each title reviewed herein–save the bonus documentary–will be released in the spring). For starters, Clarke is narrowly represented by his most notorious (Scum v1.0, banned from broadcast for its unwillingness to play nice; the still-controversial Elephant) or star-driven (Made in Britain‘s Tim Roth; The Firm‘s Gary Oldman) work, completely discounting his films about women (Christine; Rita, Sue and Bob Too) and still others that fall outside the borderline-exploitation mandate. Yet for those unfamiliar with this man who sealed his publicity doom by working in television (and therefore outside international quality circles), there is no question that the collection is a must-have, worthy of a blind purchase and benumbed marathon screenings long into the night. Clarke’s films are impossible to stop watching and impossible to forget, not as random shocks but as precision strikes against numbness. You can’t walk away from him believing that nothing can be done: his films say action must happen. Whatever that action might be, of course, is entirely up to you.

I do have quibbles with Blue Underground’s “The Alan Clarke Collection”, soon to go out of print (though single-disc issues of each title reviewed herein–save the bonus documentary–will be released in the spring). For starters, Clarke is narrowly represented by his most notorious (Scum v1.0, banned from broadcast for its unwillingness to play nice; the still-controversial Elephant) or star-driven (Made in Britain‘s Tim Roth; The Firm‘s Gary Oldman) work, completely discounting his films about women (Christine; Rita, Sue and Bob Too) and still others that fall outside the borderline-exploitation mandate. Yet for those unfamiliar with this man who sealed his publicity doom by working in television (and therefore outside international quality circles), there is no question that the collection is a must-have, worthy of a blind purchase and benumbed marathon screenings long into the night. Clarke’s films are impossible to stop watching and impossible to forget, not as random shocks but as precision strikes against numbness. You can’t walk away from him believing that nothing can be done: his films say action must happen. Whatever that action might be, of course, is entirely up to you.

| DISC 1 – SCUM (BBC VERSION) |

| Image B- Sound B Extras B+ |

| Every great director should have at least one banned film. Clarke’s is Scum, a rough-hewn and totally uncompromising dissertation on the failure of Britain’s borstal system. Made for the BBC’s “Play for Today”, it was scandalously refused broadcast, presumably because it embarrassed the wrong people. No wonder. There’s no way anybody watching the downward progress of Carlin (Ray Winstone)–who enters the boy’s prison, sets himself up as “daddy,” and presides over a world of pain in which “screws” abuse the inmates when the inmates aren’t abusing each other–could come away thinking the system works. Not only is it represented by a Jesus-freak warden completely out of touch, but the guards collude with the leaders like Carlin in order to keep order, too. Nobody believes in rehabilitation; they’re out to make each other harder.Clarke and writer Roy Minton drop you into the scrum of the borstal, and you sink or swim like everyone else. You may casually note the dehumanizations of the screws and how the oppressed inmates mistreat each other to compensate, but you have to think on your feet as various power struggles, rapes, and racist reprisals overwhelm you. Though lone middle-class prisoner Archer (David Threlfall)–who reads mail to illiterates and can see the patterns–delivers some explicit political commentary, he’s on the fringes. Brilliantly subtle, the film teaches without telling, submerging you in the environment instead of drawing diagrams and standing outside the action. The majority of editorializing is left up to you, without the benefit of distance or self-satisfaction at that. Scum is a chastening experience for blowhard conservatives and parlour liberals alike.

Scum‘s fullscreen transfer was alas derived from a weathered and extremely grainy source. The Dolby 2.0 mono sound is equally rough, but really: wouldn’t a crystal-clear presentation of one of the grimiest movies ever made kind of defeat the purpose? Extras include two commentaries: one feature-length and the other scene-specific. The former, moderated by an unidentified fourth party, teams producer Margaret Matheson with cast members Phil Daniels and David Threlfall. Daniels has only hazy recollections of things, and Matheson often goes unnoticed, yet they’re all proud to have worked on this milestone film. Matheson is quick to note Ken Loach’s spearheading of the television revolution that made Scum possible; everyone recalls “Clarkey’s” manipulative, autocratic direction, but contends that they’d do anything for him if they could. Ray Winstone rounds out the disc with commentary on two scenes: his painful introduction to the borstal life, and his attempts to turn a fellow prisoner into his gay “missus.” Scene one is largely devoted to Clarke-worship, scene two to remembering his shock at discovering a facet of prison life that has since seeped into popular mythology. |

| DISC 2 – SCUM (THEATRICAL VERSION) |

| Image A Sound B+ Extras B+ |

| You now have your choice of which borstal hell you wish to inhabit: the one that hits like a blackjack, or the one that cuts like a razor. Scum 2.0 is an entirely more orderly affair, clearly benefiting from a higher budget: the semi-formed visual ideas of the BBC original are deployed with greater sophistication (especially the set-up of the climactic riot), while the hospital-clean walls radiate oppression like some social-realist Clockwork Orange. Even though the technique has become more precise, however, one misses the overpowering funk of the banned original, which made a virtue of necessity in its shaggy haircuts, peeling wallpaper, and generally forlorn haphazardness. Watch the BBC rendition first and the remake may look too slick; watch the remake first and the TV version may look clumsy and less focused.That said, the distinction is largely academic. Much of the same material is covered verbatim, with a few extended sequences: Archer, now played by the far more elegant Mick Ford, gets a few more scenes in which to sound off, and a suicide raises temperatures for the final tragedy. Where the earlier version has the edge is the scene of Carlin taking his “missus,” a glaring omission that unfortunately changes the tone of the character (though there’s a mock wedding that almost compensates). Nevertheless, there’s no denying that the upgrade from BBC afterthought to full-fledged motion picture has given things an aesthetic force they previously didn’t have. Whether that force leaves other felicities in the dust is a matter of personal taste.

Exacerbating the discrepancy between the two, the BBC version is overmatched on DVD. Having previously seen it on a crusty old VHS copy, I was shocked to learn that the theatrical remake’s palette actually included white, and Blue Underground has rendered that gleaming hue with intense sharpness and clarity in a 1.66:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer. The slightly gratuitous Dolby Digital 5.1 remix exhibits full sound from the forward soundstage but rarely utilizes the surround channels in a vital way. Extras begin with a commentary from Ray Winstone and moderator Nigel Floyd. Winstone is less snarky and cute than Daniels and Threlfall are on disc one; he’s genuinely proud of the statement the film made as well as what he learned at the hands of Clarke. He’s also far more concerned with Scum‘s themes, and if he’s perhaps a tad fumbling in his explanations, he and Floyd have a wonderful time bringing out the finer points of borstal living. In the meantime, a 17-minute piece from 1999 throws the spotlight on writer Roy Minton and producer Clive Parsons, with Parsons a tad fixated on irrelevant Cagney-esque elements in Carlin’s character. Mostly, he’s on issue, however, and gets more good words in than Minton does. In fact, as his script is a model of the form, it’s sad that Minton doesn’t get more screentime. A small poster-and-stills gallery rounds out the disc, where we learn that the film was paired on video in the UK with Bad Girls Dormitory! |

| DISC 3 – MADE IN BRITAIN |

| Image B+ Sound A- Extras A- |

| Having placed us at the centre of Hell, Clarke turned his attention to a circle poised above the furnace. Trevor (Tim Roth) is a smart young lad who’s aware of his tragically limited options in Thatcher’s employment-poor Britain and is, as the counsellors like to say, very much in touch with his feelings. He’s also a Nazi skinhead out to cause as much trouble as he can, although hatred is a relative matter, as he’s also been fobbed off on a system that can sympathize or antagonize but can’t do a damned thing to help him. His actual racism floats a bit (he empathizes (to a point) with Errol (Terry Richards), his black roommate at the “assessment centre” where he’s dropped), but with no options, he’s quite happy to beat up on whoever’s handy. As brutal and hateful as Trevor is, you have begrudging respect for him: he’s not constructive because he knows there’s nothing around to build with. As with Scum, Made in Britain deposits you into a world with ineffectual or unsympathetic social workers and a hero just this side of terrifying. Like the earlier films’ Carlin, we know little beyond Trevor’s awareness of the hopelessness of the situation and willingness to do absolutely anything to make life bearable–in this case, the easy thrill of smashing windows, terrorizing immigrants, and sniffing glue in stolen cars. Racist or not, the real target of his terror is the mostly white social workers who tell him to straighten up and fly right, as if a future of minimum-wage labour (or, more likely, the dole) could be seen as a satisfying way of marking time. So Trevor charges through each scene like a bat out of hell, through a labyrinthine set of paper rules that lead him by the end into the borstal cul-de-sac of Scum.Made in Britain‘s fullscreen transfer is grainy, even allowing for the production’s 16mm origins, but its appearance on DVD is cleaner and ruddier than that of the BBC Scum. The Dolby 2.0 mono sound is terrific, mind you, potent in spite of the project’s lo-fi origins. Two commentaries supplement the film, one with actor Tim Roth, the other with writer David Leland and producer Margaret Matheson; Blue Underground’s David Gregory serves as moderator. Roth doesn’t have anything particularly insightful to say about his time–it was his first major role, and he was quite intimidated–but he’s full of goodwill and does remember the skinheads in his past who would regularly beat him up. The Leland/Matheson track is superior and superb, with Leland pointing out the importance of Steadicam and fast film stocks to the shooting and touching on his other scripts in the same series, not to mention the wild accusations of loathsome British tabloid THE SUN. Matheson, again, interjects only occasionally. Roth resurfaces in a 5-minute video interview to discuss his greenhorn status and praise Clarke, while a small poster/stills gallery provides more shots of Roth glowering than previously thought possible. |

| DISC 4 – THE FIRM | ELEPHANT |

| THE FIRM: Image A- Sound B+ |

| Much has been made about The Firm‘s apparently shocking reversal of expectations: instead of depicting football hooligans as yobbo proles, it offers Bex Bissell (Gary Oldman), a comfortable lower-bourgeois estate agent who runs a “firm” of thugs on the side. The point of the film is not class warfare tit-for-tat, though, but rather an examination of the thrill of power engendered by codes of masculinity. Bex is linked with Scum‘s Carlin and Made in Britain‘s Trevor by his determination to climb to the top of the shit-heap, although his mountain is merely boredom: he’s somehow not satisfied with his gentrified lot and thus searches for a rush in thoroughly pointless skirmishes with other firms.The Firm lacks the conceptual purity of the other films in the collection. Scenarist Al Hunter lacks Roy Minton’s feel for environment and the precise sociology of David Leland; Bex’s chief rival, a wealthy albino dubbed Yeti (Philip Davis), is less a human being than he is a great blaxploitation villain. Still, the script throws a wrinkle on the simplistic view of Clarke as a hand-wringer for the downtrodden: the director is smart enough to see the self-destructive attraction of hooliganism, and Hunter skilfully draws the insane details of men signing up for abuse by not only arbitrary enemies but also each other in the name of “belonging.” The negative socialization of the other two features is endured here on a volunteer basis, making Clarke’s total project far more troubling than a simple liberal “no.”

Like the other televised titles, The Firm‘s full-frame presentation is beset by grain, but the clarity of the image and richness of contrast betray advancements in film stock since Made in Britain. The Dolby 2.0 mono track sounds a tad muffled but won’t cause any major headaches. There are no extras beyond a photo gallery consisting of production stills and behind-the-scenes shots. |

|

|

| ELEPHANT: Image B Sound B+ Extras A- |

| Elephant is a brutally structural take on the Northern Ireland “troubles” in which an array of killers approach an array of victims, pull the trigger, and walk away: you have the Steadicam stalking; the murder; the escape; and a shot of the victim to let it all sink in. The End. At a trim 38 minutes, it’s exactly the right length–any less and it wouldn’t have the cumulative impact, any more and you’d wind up completely jaded. As it stands, this is Clarke at his most formally intense, taking his environmental approach to political material and eliminating everything except acts of violence. No arrows to demarcate Catholic from Protestant, no titles to suggest the organizations responsible, and no historical background explaining it away. You live in a world of hurt–and then you die.The “responsible” critique is that you’re ultimately left without any political recourse to defend yourself: this is happening, it will continue to happen, and there’s not a damn thing you can do to stop it. Perhaps. But what Clarke understood better than any other director is that traditional analysis can micro-manage lived experience out of existence. Elephant is an attempt to rescue the things that get lost in reportage: the fact that someone must actually carry out the deed, and that the universe is silent for the deceased. It’s about living day-to-day with acts other countries may consider extraordinary and outrageous.

The full-frame transfer is a regression in terms of quality, but the content sanctions the grittiness. The Dolby 2.0 mono sound is probably as sharp as can be expected from a BBC quickie. As for bonus material, Mark Kermode moderates a film-length commentary with Elephant producer Danny Boyle. Once the requisite gushing is out of the way, the commentary is supremely on-issue, full of enough background info on the Northern Ireland shoot that you almost fail to notice that Boyle has gone on to completely betray everything Clarke stood for. Rounding out the platter, a 5-minute featurette assembles talking-heads with the likes of Gary Oldman, David Hare, and Clarke’s daughter Molly Clarke, all of whom–with the exception of a cliché-spouting Oldman–offer insight into the movie’s evolution and impact. |

| DISC 5 – DIRECTOR: ALAN CLARKE |

| Image A Sound B+ |

| Sadly, “The Alan Clarke Collection” finishes up with a wholly underwhelming BBC documentary completed not long after Clarke’s death in 1990. It’s not so much a probing analysis as it is a tentative tribute to the king. David Leland presides over interviews with colleagues and collaborators like Stephen Frears, Ray Winstone, Phil Daniels, Lesley Manville, and Gary Oldman, whose soundbites lean towards the usual noncommittal blather. Director: Alan Clarke races through Clarke’s working-class background (one wants to know more about his stint as a coal miner) in order to offer (rushed) appreciations of the man’s films that range from “they had an immense stillness” to “he never told you what to think.” I happen to believe that Clarke had pretty definite ideas about what to think, but the piece is uninterested in sussing out his extremely complex position.Left unexamined is Clarke’s highly manipulative approach to directing actors. Daniels reports that Clarke told the black kids in Scum‘s murderball scene that the white kids were targeting them and vice versa in order to get the realistic melee he sought. Incredibly, Clarke’s bullying seems to have left few scars: Where the entourage of Fassbinder was bound to him by fear and hatred, survivors of Clarke’s methods speak of him with awe and respect. The type of person who could instil absolute trust with such calculating behaviour is an enigma worthy of a deeper exploration than this glorified greatest-hits album.

Director: Alan Clarke nevertheless looks well-preserved in the set’s fullscreen presentation; Leland’s unfortunate choice of shirt sports better fine detail and colour saturation than it probably deserves. The Dolby 2.0 mono sound is comparatively run-of-the-mill. The only extra is a paltry text-based bio for Clarke. “The Alan Clarke Collection” docks on the format in a digipak with a 5-disc wingspan that folds up into a sturdy cardboard container. |

- Scum ’77

78 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region-free; Blue Underground - Scum ’79

98 minutes; R; 1.66:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1, English Dolby Surround, English 2.0 (Mono); English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region-free; Blue Underground - Made in Britain

73 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region-free; Blue Underground - The Firm

70 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region-free; Blue Underground - Elephant

38 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region-free; Blue Underground - Director: Alan Clarke

53 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region-free; Blue Underground

![Wolf Creek (2005) [Widescreen Edition - Unrated Version] - DVD + Hostel (2006) [Unrated Widescreen Cut] - DVD|[Director's Cut] - Blu-ray Disc wolfcreek](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2007/10/wolfcreek.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)

![Hostel Part II (2007) [Unrated Director's Cut] - DVD hostelpart2](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2007/10/hostelpart2.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)

![O Lucky Man! (1973) [Two-Disc Special Edition] + Never Apologize: A Personal Visit with Lindsay Anderson (2008) - DVDs 6a0168ea36d6b2970c0168eb93a6f4970c-600wi](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/6a0168ea36d6b2970c0168eb93a6f4970c-600wi.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)