****/**** Image A Sound A Extras A+

starring Martin La Salle, Marika Green, Jean Pelegri, Dolly Scal

written and directed by Robert Bresson

by Walter Chaw Manny Farber described the films of Robert Bresson as “crystalline,” and it’s hard to argue with the singular idea of purity represented by that word: they’re all of gesture and implication, reduced down to the purest grist so that the powder of dramatic movements, rubbed together, might hum in miniature perfection. Diderot, Tolstoy, and especially Dostoevsky are sent to the kiln in Bresson, emerging at the end as a distillation thick with the observation that human behaviour, winnowed down, is only as mysterious as the mechanical motions of insects. When you use a term like “crystalline,” you evoke clockwork–the inner workings of music boxes, say. It’s wilfully, damnably, emotionally inscrutable, of course, and if it also calls to mind a watchmaker and his intricate art, then find another explanation for Bresson’s fascination with, and eroticizing of, the secret life of hands.

Bresson’s Pickpocket is less an austere film than it is a film about austerity–an existential, transcendental exercise (and a literary–and literate–one, too) dependent on physical actions as opposed to emotional cues or narrative arcs. As you watch it, you begin to realize how programmed you’ve been by the grammar of visual narratives: Bresson has so stripped away the flesh from his picture that at the moment of its greatest generosity, that sense of being overcome arises from the realization that along the way, you’ve become very much the instrument of the film’s sense. I’m not suggesting that the picture is surreal (or even Brechtian), but that it has the flavour of Camus or, indeed, Dostoevsky in the requirement that the audience provide the soul and conscience of the piece, along with a good deal of the action. It should be clarified, though, that while Pickpocket is far from a cold film, in the titular cutpurse Michel’s (Martin La Salle, a sort of Anthony Perkins/Montgomery Clift hybrid) affectedly impassive search for connection, there is an extraordinary negative space reserved for the contemplation of the floridity of emotion and desperation. In its loneliness and struggle, Pickpocket (like every Bresson film) is essentially humane; in this Freudian noir performed by clockwork phantoms, there is an unbearable intimacy in the mute coming-together of eyes over a forbidden rendezvous (Michel fingering a purse, or caressing a man’s chest in the act of taking his wallet) that, more often than not, seems an act of mutual transgression.

That knotty complicity seeps, too, into the positioning of Pickpocket‘s father godhead–Jean Pélégri’s L’inspecteur Principal of the local constabulary, lumpish and slightly oily like Orson Welles’s treacherous police captain Quinlan in the previous year’s Touch of Evil–and mother/whore Jeanne (Marika Green, for whom Natalie Portman is a dead ringer). Michel’s obsessive orbit around one and doomed embrace of the other locates the Freudian avenue through which to explore the picture. Certainly less so than in Bresson’s later Mouchette (if sharing several similarities with his masterful Diary of a Country Priest), Pickpocket‘s love triangle between a man and his would-be parents–inevitably resolved in blood, isolation, and consummation–speaks to a very particular developmental psychodrama. In this way, theft as the prime mover gains the burden of virginity and the loss of it, bolstered by the fact that Michel never appears to gain materially from his conquests as much as he accumulates a weight of sin that demands redress. By focusing, too, on Michel’s urgent desire for the brief connections with his (mostly) male victims in public meeting places (his repulsion of Jeanne and, in one curious moment, his fascination with a baby), there is, too, the spectre of sexual identity struggling for clarification through Michel’s actions.

At its heart, however, Pickpocket is the erotic sublimated into ritual–an Alexander Pope poem denuded of its purpleness, leaving just the sign and signified behind. (Major moments happen offscreen in the picture–only the consequences for autopsy remain.) Bresson’s films are the most sublime expression of the powerful, illicit sexuality of the movement of moving pictures against a subjective audience. They describe the junction between the animal mendacity of product and the wish to ascribe more to gesture than to function. There are echoes of Bresson in the romantic work of schematized filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch or Wim Wenders or, more to the contemporary cultural fulcrum, Jean-Luc Godard (Alphaville and Week End, in particular)–and in time, Bresson’s output will fall farther away from traditional coherence, like Godard’s has.

But unlike Godard, Bresson shows little interest in the nihilism of that kind of deconstruction, more captivated as he is by how something as automatic as a person can take on the forms and imitations of Grace. Look at a moment where Michel, then in training himself in the dulcet choreography of his petty crimes (compare the treatment of pickpocketing in this picture to fly-fishing in others), is summoned to the sick bed of his terminally-ill mother (a scene repeated in Michael Haneke’s shrine to Bresson, Caché): hands we’ve seen metastasizing into “supple” instruments of larceny in a rapturous, almost holy, montage are now engaged in first comfort, then supplication, then grief, before finally, in the journal entries that bridge sequences, the creation of legacy. When Michel sits at a table, casing a bank’s customers, his hand rests on the table before him like a second character–a separate personality, or an aspect of a personality, or an ingenious animal asleep at his master’s foot, capable at his call of running through every motion of human expression but requiring of an audience (a victim, lover, mother, reader, witness) to attain immortality.

THE DVD

The Criterion Collection issues Pickpocket on DVD in a lovely 1.33:1 transfer that minimizes such age-related artifacts as flickering sans the general perils of digital over-compensation. They’re pros at this, of course, and we’re in good hands again here. There is a sense of textile to Bresson’s pictures, of looking at something projected on parchment; I’ve often wondered whether a “cleaner” master would create a different effect–but like Guy Maddin’s somewhat smug “recreations” of nickelodeon shorts, there’s a fascination in the way we access Bresson now, and I confess that I enjoy the contemporary mystery. Pickpocket‘s original French audio is preserved in crystal clear 1-channel mono, while on another track, Bresson scholar James Quandt (author of the Cinematheque Ontario’s Kon Ichikawa monograph) offers a brilliant, illuminating feature-length yakker that covers every major interpretation of the text with enthusiasm and clarity. It’s an invaluable listen for newcomers and long-time Bresson admirers alike, providing both overview and minor epiphanies. Meanwhile, an optional video introduction from Paul Schrader (14 mins.) sees the filmmaker (himself a former film critic mad for the transcendentalists) loosely comparing Pickpocket with his own screenplay for Taxi Driver.

“The Models of Pickpocket” (52 mins.), directed by Babette Mangolte, catches up with the principal cast of Pickpocket circa 2003 and reveals itself to be the work of a true zealot: passionate, but without much more guiding its existence than its mission. The highlight comes with the still-beautiful Green, who describes Bresson’s methodology and how his theory of blankness had a dampening effect on future careers for some of the amateur actors working under him (“It wasn’t the characters we were giving ourselves to, it was this man”) before producing her shooting script (“Uncertainty” was the original title of the piece), annotated with in-depth directions from Bresson himself. An excerpt from a 1960 episode of “Cinépanorama” (6 mins.) features a bittersweet interview with the director on the subject of Pickpocket–bittersweet because the film’s reception at the time was, considering its proximity to the release of Godard’s far more accessible Breathless, “cool” at best. Bresson identifies the anxiety of the picture, most of it arising from the unconventionality of its approach, as the chief bogey of its popular failure.

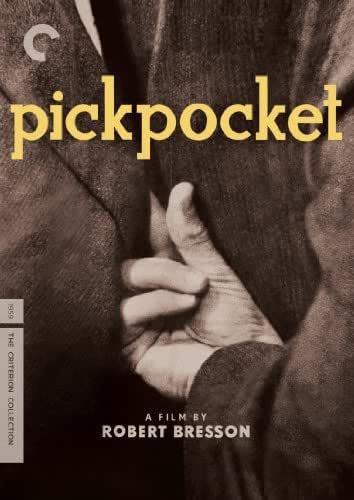

A “Q&A on Pickpocket” (13 mins.), conducted with Green and filmmakers Paul Vecchiali and Jean-Pierre Améris after a 2000 screening of the picture at the Rellet Médicis in Paris (not a full house, it bears mentioning), is sadly as uncomfortable as these things usually are. “Kassagi” (12 mins.) is an excerpt from the sleight-of-hand artist’s show La piste aux étoiles (broadcast on French TV in 1962) in which the master illusionist (and technical advisor on Pickpocket) threads razor blades on a string with his tongue in a ruffled shirt. The picture’s original theatrical trailer (2 mins.) has been remastered and, laudably, it honours Bresson with its lack of soundtrack and misleading hyperbole, though it can’t quite resist positioning itself as something of a doomed psychological thriller. Quiet ambient crowd noise plays beneath the static main menu (wallpapered with an image of three hands clasped in what we know is a moment of capture but that suggests–like so many hand movements in the film–a mysterious, alien, cephalopodian courtship) in another demonstration of Criterion’s care in not only presenting the picture, but understanding it as well.

75 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; French DD 1.0; English (optional) subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; Criterion

![Pickpocket (1959) [The Criterion Collection] – DVD](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2006/01/pickpocket.jpg?fit=800%2C600&ssl=1)

![Breathless (1960) [The Criterion Collection] - 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray Combo A.bout.de.souffle.1960.UK.STUDIOCANAL.UHD.BDRemux.2160p-rutracker.mkv_20241028_165427.927](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/A.bout_.de_.souffle.1960.UK_.STUDIOCANAL.UHD_.BDRemux.2160p-rutracker.mkv_20241028_165427.927.png?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)