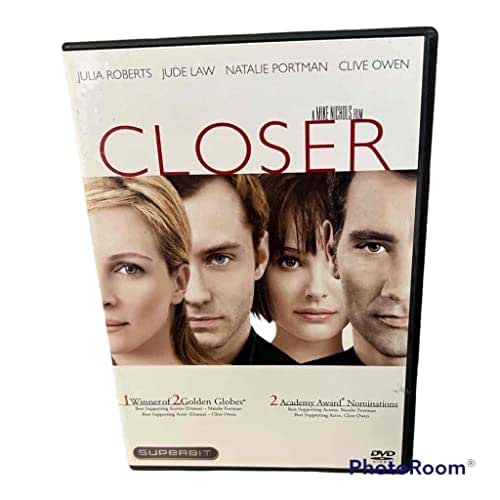

***/**** Image A- Sound A+

starring Natalie Portman, Jude Law, Julia Roberts, Clive Owen

screenplay by Patrick Marber, based on his play

directed by Mike Nichols

by Walter Chaw A girl takes off and cleans a guy’s glasses on her jacket as he’s talking, then gently replaces them. She asks him what a euphemism for her would be, and he tells her: “Disarming.” “That’s not a euphemism.” But he assures her that it is. A girl takes a picture of a guy, a guy talks to another guy through the anonymity of a computer screen, a guy visits a girl performing at a peepshow and offers her a large amount of money to tell him her real name. A guy meets a girl at an aquarium where she’ll go to steal pictures of strangers as they look at the captive marine life in the blue glow of sharks circling. Mike Nichols’s Closer is beautifully directed from Patrick Marber’s adaptation of his own play, shot with an extraordinary amount of verve and resonance around the loaded themes of ways of seeing (glasses, cameras, correspondence) and their connection to voyeurism, objectification and confinement, and forms of physical and emotional abuse. A scene in the middle set at a photo exhibit crystallizes every thread: people milling about, buffeted by giant projected reproductions of ‘disarmed’ subjects, coming and going and talking of Michelangelo. It’s overwritten but clever, too, doing a dangerous little dance along the edge of relevance and camp like a film from the 1970s (Nichols’s own Carnal Knowledge, sure, but more like another film from 1971, Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs), only really failing in one performance and a seeming inability to follow through on its central punch. It’s a courageous mainstream picture, no question, though it’s mainly courageous in comparison to its contemporaries. Was a time when films like this and more toothsome were the norm and not the semi-quailing exception.

by Walter Chaw A girl takes off and cleans a guy’s glasses on her jacket as he’s talking, then gently replaces them. She asks him what a euphemism for her would be, and he tells her: “Disarming.” “That’s not a euphemism.” But he assures her that it is. A girl takes a picture of a guy, a guy talks to another guy through the anonymity of a computer screen, a guy visits a girl performing at a peepshow and offers her a large amount of money to tell him her real name. A guy meets a girl at an aquarium where she’ll go to steal pictures of strangers as they look at the captive marine life in the blue glow of sharks circling. Mike Nichols’s Closer is beautifully directed from Patrick Marber’s adaptation of his own play, shot with an extraordinary amount of verve and resonance around the loaded themes of ways of seeing (glasses, cameras, correspondence) and their connection to voyeurism, objectification and confinement, and forms of physical and emotional abuse. A scene in the middle set at a photo exhibit crystallizes every thread: people milling about, buffeted by giant projected reproductions of ‘disarmed’ subjects, coming and going and talking of Michelangelo. It’s overwritten but clever, too, doing a dangerous little dance along the edge of relevance and camp like a film from the 1970s (Nichols’s own Carnal Knowledge, sure, but more like another film from 1971, Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs), only really failing in one performance and a seeming inability to follow through on its central punch. It’s a courageous mainstream picture, no question, though it’s mainly courageous in comparison to its contemporaries. Was a time when films like this and more toothsome were the norm and not the semi-quailing exception.

Like Paul Mazursky’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, Closer concerns the roundelay trysts and retreats of four people: Larry (Clive Owen) & Anna (Julia Roberts) & Dan (Jude Law) & Alice (Natalie Portman). Larry is a dermatologist who describes the heart as “a fist covered with blood” and himself as a caveman, and he dispatches a lover one night with “Fuck off and die, you fucked-up slag.” Anna is a photographer, Dan is a failed novelist, and Alice, a stripper, is the subject of Dan’s failed novel. Anna’s read the novel (called The Aquarium, perhaps in honour of the film’s hermetically sealed quartet) and admires it, so she kisses Dan while shooting the portrait for his book jacket. Alice finds out and confronts her; out of malice, Dan accidentally sets Larry up with Anna, but Dan loves Anna…and Larry loves Anna…and Alice loves Dan… And Anna? Who knows about Anna. Closer is complicated like love can be in its suggestion that love is the veneer of civilization slapped on sex and violence–and that it’s this veneer, not the sex and violence, which causes damage.

Given room to stretch at last, Law rises to the occasion. But Clive Owen is the star of this show, the Iago and the tempest, Caliban at the heart of Closer‘s waves of mutilation. He takes no prisoners and he’s mesmerizing, all virility and rage. Roberts has an ineffable quality on the big screen, and the moments she shares with Owen–particularly a brutal argument (“He tastes just like you, but sweeter”)–rank as possibly the best and most honest that she’s ever committed to film. There’s a bitterness to her in Closer; she’s wan and quick to strike. It’s a fabulous, diaphanous performance, in other words. Consider that when she flashes her celestial choppers, it comes as something of a shock that she can. Besides the weakness of its conclusion (Peckinpah may have had it right that the only way to end an allegory about the root of fucking is through an orgy of violence), Closer suffers most at the hands of a badly overmatched Natalie Portman. I know she’s beautiful (you tend to want to genuflect before the carved planes of that face), but her voice and delivery have the plaintive, flinty quality of an eight-year-old’s. She’s described at one point as having “the moronic beauty of youth,” and there’s possibly never been a better description of her as an actress. It’s a quality that made her perfect and indelibly memorable as a woman-child in Léon but comes off as artificial and somehow constructed in Closer. The role of Alice would have gone to Jennifer Jason Leigh a few years ago, and the gulf between her and Portman is not only wide but also, I’m starting to believe, unbridgeable by the starlet. It’s interesting to think she used to seem squandered in George Lucas’s Star Wars prequels–between this and Garden State, she demonstrates that the fit in Lucas’s folly is actually pretty comfortable.

That being said, women are tertiary or afterthoughts in Closer: they’re pawns, the things Larry uses to ruin Dan. Both Anna, a ghostly catalyst, and Alice, a cipher and a caricature, haunt the film as the embodiments of ethereal perfection that Dan and Larry each adore. (Soiled Madonna, whore ascendant.) They are objects lovingly captured by Nichols (re-teaming with his Angels in America cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt) the way that Anna lovingly photographs her “sad people” (including Alice), given an impossible glow and shown in almost every scene–most tellingly, the last–as an idealization frozen in the amber of the aggressive male gaze. Dan, as played by Law, is driven by his wandering eye–he’s the grown-up version of his recent disastrous turn as Alfie, a guy who can never quite reconcile the gentility that gets him laid with the beast that demands the deception and the hunt. The film is about how men are savage and horny and how denying the intrinsic baseness of the cult of masculinity leads to self-deception and disaster. It’s the lesson of Straw Dogs told in polite terms (the sexual violence (“Go ahead, I’ve been hit before,” Anna says) is all offscreen), where a man thinking himself genteel proves infinitely crueller than the one knowing himself as an animal.

It’s ultimately no surprise that the sole moment in which physical violence occurs centre stage is reserved for that erstwhile champion of civilization. But while Nichols magnifies this turning point with slo-mo, freeze, and dissolves, it still lacks the kind of force that a film this nasty requires. It’s a flaccidity reflected in a simpering double-epilogue that verges dangerously close to affirmation of everything that Closer, up to then, had attacked as facile and disingenuous, driving home the irony of Alice’s remarks about Anna’s pictures at exhibition: “These photographs make sadness so beautiful that it’s a lie.” While Closer should be commended for the few ugly truths it grips in the vise of its bloody heart, it pulls out just before it climaxes. What’s left is sweaty and rough, but weirdly impotent just the same. Originally published: December 3, 2004.

THE DVD

by Bill Chambers It’s hard to bemoan the lack of supplementary material when a bare-bones DVD looks and sounds as good as Closer‘s. Released under Sony’s Superbit imprimatur despite committing minor infractions against the Superbit manifesto, the film receives a 1.81:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer that does Stephen Goldblatt’s gleaming cinematography untold justice. But though I was frankly amazed by the piercing clarity of the image, the source print cries out for a good scrubbing from time to time, something that can actively undermine the picture’s aesthetic. (The surface is everything in Closer.) Faring better, the 5.1 soundtrack is an immaculate reproduction of a modest mix; contrary to the way that most sites seem to evaluate DVDs, we base our A/V grades on fidelity to intent, not on whether we feel consoled about having purchased expensive equipment. Closer is a movie composed of conversations, and as such, it sounds marvellous–especially in DTS, which brings more depth to not only the dialogue, but also the occasional splash of music. Under extras, find trailers for Guess Who, Bewitched, Spanglish, Hitch, House of Flying Daggers, Being Julia, A Love Song for Bobby Long, and Closer (the first three of which cue up on start-up), plus the video for Damien Rice’s interminable but somewhat hypnotic “The Blower’s Daughter.”

104 minutes; R; 1.81:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1, English DTS 5.1, French Dolby Surround; CC; English, French subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; Sony