THE COCOANUTS (1929)

**½/**** Image C- Sound C-

with Oscar Shaw and Mary Eaton

screenplay by Morrie Riskind, based on the play by George S. Kaufman

directed by Robert Florey and Joseph Santley

ANIMAL CRACKERS (1930)

***/**** Image C Sound C

with Lillian Roth and Margaret Dumont

screenplay by Morrie Ryskind

directed by Victor Heerman

MONKEY BUSINESS (1931)

***½/**** Image B+ Sound C+

with Rockliffe Fellowes and Harry Woods

screenplay by S.J. Perelman and Will B. Johnstone

directed by Norman McLeod

HORSE FEATHERS (1932)

****/**** Image C+ Sound B

with Thelma Todd and David Landau

screenplay by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby and S.J. Perelman and Will B. Johnstone

directed by Norman McLeod

DUCK SOUP (1933)

****/**** Image B+ Sound B

with Margaret Dumont and Raquel Torres

screenplay by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby and Arthur Sheekman and Nat Perrin

directed by Leo McCarey

by Walter Chaw Popular wisdom holds that the Marx Brothers were best at Paramount, before the public disapproval of their satirical masterpiece Duck Soup sent them fleeing with proverbial tails between their legs to MGM and an ignoble end in a series of progressively worse, studio-sterilized soft-shoe routines. But the truth is that the Marxes didn’t hit their stride until at least their third picture for Paramount, Monkey Business: the first couple of flicks (The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers) are laden by the team’s dependence on played-out stage productions and the “oh my god” quality of the early talkie, in which actors played to microphones hidden in flower pots, extras stared straight at the camera, and the florid gestures of the theatre were adhered to with pathological devotion.

A lot of that learn-as-you-go attitude mars The Cocoanuts, locating it as a historical artifact of the vaudeville stage–where the Marx Brothers made their mark–more than of the dawn of the talkie. (An effect exacerbated by the fact that without looping, then in its infancy, any movement of the cameras would result in a horrendous racket, thus the film’s point-of-view is static, replicating the experience of sitting in a fixed spot in relation to the stage.) What the film does well, though, is identify the comedy troupe as one whose humour needed the sound era before it could flourish in motion pictures–recalling that the Marxes’ first celluloid effort, a self-financed, seven-thousand dollar silent called Humorisk, was received with such hostility during its one and only screening that the Brothers consigned it to flame.

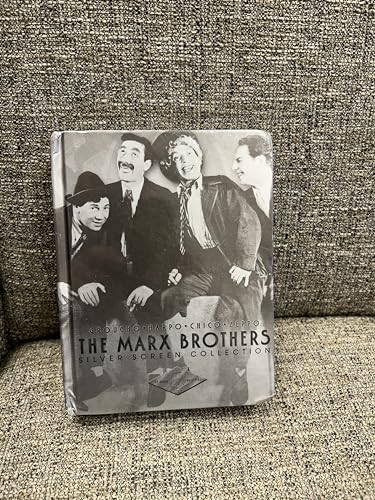

So The Cocoanuts, a straight adaptation of the Marx Bros. Broadway smash shot for four days a week with Wednesdays off to accommodate matinee performances of “Animal Crackers”, became the top-grossing film of 1929. A loose love subplot (involving Mary Eaton and Oscar Shaw) like those derided–by me, lately–in their MGM years ties the loose shenanigans of the Brothers together as hotel manager Hammer (Groucho) schemes to sell Florida swampland while criminal elements Harpo and Chico conspire against him. Margaret Dumont’s Mrs. Potter establishes the archetypical Groucho foil in grand style, and indeed, the elements of the film that are uniquely Marx (the double entendres, the puns) have a feeling of freshness here that suggests at once a lack of polish and a certain energy. Although the language is mangled in a way that indicates a supreme mastery of speech, with the classic “why a duck” gag executed with trip-hammer precision, so much of The Cocoanuts is inaudible or muddy (and even more given over to sappy crooning and bizarre musical interludes courtesy Irving Berlin) that it’s hard to winnow the wheat from the chaff. The true benefit of starting at the beginning, as it were? Once you reach Duck Soup, the final film in Universal’s new, handsomely-packaged but poorly-outfitted box set, you’ll have a better appreciation of its satire of awkward Hollywood musical hybrids.

The origin of Groucho’s theme song “Hooray for Captain Spaulding,” 1930’s Animal Crackers reunites the boys (Groucho, Harpo, Chico, Zeppo) for another–their last–straight adaptation of one of their Broadway hits, an art caper that represents a quantum leap forward from their successful but badly dated talkie debut The Cocoanuts. There’s a moment early on when Capt. Spaulding (Groucho), wooing ace foil Margaret Dumont, refers to Eugene O’Neill and then proceeds to make three O’Neill-inspired asides on a focus-pulled proscenium. The breaking of the fourth wall was a constant in the Marx Bros. repertoire, but the sophistication in this instance to inject satirical commentary on another artist in a different medium suggests the first hints of a burgeoning post-modernist cartoon aesthetic; here we see not only the genesis of the animated tattoo that will appear in Duck Soup, but also the birth of the anarchic cymbal crash of a randy animator like Tex Avery. Coupled with Chico’s Ravelli character musing that his gambling and womanizing will be the ruin of him (self-knowledge mirroring Chico’s actual Achilles Heels) and Animal Crackers, seventy-five years ago, played the meta card with an almost brutal invention.

Groucho’s delivery feels fresher here than in The Cocoanuts: the impossible verve with which he says, “You know, you two girls have everything. You’re tall and short and slim and stout and blonde and brunette, and that’s just the kind of a girl I crave,” almost by itself explains his lasting appeal. He’s insouciant and stuffy, urbane and feral, and even though he enters the picture on the backs of literal African porters, there is in the Marxes’ work such a sympathy for the underestimation of immigrants and minorities that its attitudes feel fraternal and contemporary rather than prehistoric. Concern about class struggle anchors Animal Crackers in the New York ghetto, where the Marx boys sharpened their tools–the film goes so far as to take a sly dig at cultural imperialism in the discovery of a polar bear in Africa: anaemic and rich, it could live where it wanted. With a subplot about the counterfeiting of paintings and, later, a bit in which Groucho adopts the guise of a Scotland Yard dick, the troupe’s throughline of the lie of personal identity (as far as it’s attached to material possessions and social rank) likewise clicks into place.

Teutonic producer Herman Mankiewicz told his revolving door of writers for the third (surviving) Marx Bros. film Monkey Business, “If Groucho and Chico stand against a wall for an hour, that’s enough of a plot for me.” Norman McLeod, a quiet workaday director, found himself at the helm of just that: one hundred or so gags and puns strung together by little more than a sort of manic energy. The first in the troupe’s startling run of dense, anarchic comedies, it coincided with the heart of the Depression (which made Groucho himself temporarily destitute) and arrived not long after the death of the Marx matriarch, Minnie. It’s almost as though the twin indignities of financial ruin and personal tragedy, then, unleashed the Marx boys to plough new ground and assert themselves on the silver screen in the same way they had on stage. McLeod remarked once that his contribution was minimal before the tyrannical nonsense of his stars and that the film was mostly ad-libbed by the antic performers, much to the consternation of the writing team.

Jettisoning long-suffering foil Margaret Dumont for willowy moll Thelma Todd, Monkey Business tackles the budding gangster genre full-on through a subplot about organized crime that jibed perfectly with their career-long interest in immigrant issues, class, and money. Contemporary, the very model of hip, the film–despite a few creaky references to Maurice Chevalier–maintains its currency because of its heightened awareness of transcending social mores, of breaking the static camera sets of their earlier talkies (dolly shots and swooping zooms augment the liquidity of the Brothers’ patter), and of taking a few extreme risks with regards to the level of sexual suggestion. (“Love flies out the door when money comes innuendo.”) The standard love story is not so much of an impediment this time, while the musical bridge actually integrates into the pulse of the piece; Monkey Business is probably only bettered by Horse Feathers and Duck Soup in the Marx library. The highlight of the piece is an extraordinarily literary moment wherein mute Harpo infiltrates a Punch & Judy puppet show, only to establish himself as the heir apparent to the puppet’s crown as he lays waste (along with his brothers) the staid conventions of society at large. He’ll later even wield a Punch-like big stick, striking Groucho across the nut with a lead pipe inside a feather.

A film that would by itself cement the Marx Brothers as the perpetrators of one work of pure comic genius, Horse Feathers is the troupe’s first masterpiece and the first film to pull together all of their throughlines and tendencies. It hits the ground running with the sort of fanfare introduction that will also introduce Duck Soup, and what the curtain pulls back to reveal might appear to be unrestrained chaos but is in fact a meticulously calculated attack on institutions of higher education and on the manic ebbs and flows of American business and the simmering veneration of our sports culture. The finale, set during a football game, remains the best metaphor for the rickety, banana-peel futility of the rules that govern our moment-to-moment. It’s a canny exploration of the American Dream, in other words, a look at how this country presented to the immigrant Marxes the promise of wealth and opportunity with the caveat that for as quickly as the summit is reached, the bottom is achieved in half the time. It’s a lesson learned by a United States still reeling from the Great Depression that the naturally moribund Groucho took very much to heart.

Groucho is front and centre as Professor Quincy Wagstaff, the head of Huxley College (an interesting synchronicity in that Aldous Huxley’s own social satire Brave New World was published the same year that Horse Feathers was released), introduced from the wrong side of the stage, wielding a razor and a hatful of what feels like aggressive discontent. Zeppo is his straight-arrow boy, Chico an ice man, and Harpo a dogcatcher, and the quartet seem to live by Wagstaff’s sung credo: “Whatever it is, I’m against it.” (Remember, this is a good twenty-some years before Marlon Brando promised to rebel against whatever you got.) The picture is avant-garde in a way that approaches dada, crumbling institutions in art and popular more through a medium that would forget that it is itself an art form before the French remembered. A fourth wall-breaking aside from Groucho even tears down the Marx convention of piano and harp interlude by Chico and Harpo: “There’s no reason you folks shouldn’t go out into the lobby till this thing blows over.” Horse Feathers is post-modern before the term gained any kind of resonance in the cinema, establishing itself in this way as the grandfather in spirit and fact of both Tex Avery and Billy Wilder. It’s so sharp that you never notice the knife between your ribs until you’re sinking to the floor. For a brief span of two films (this and Duck Soup), the Marx Brothers occupied the same rarefied air as Charlie Chaplin: angry, wistful, and, it’s true, sublime.

After riding the wave of Depression-era cynicism, the Marx Brothers found themselves with Duck Soup at the dawn of The New Deal and its concurrent spirit of nationalistic pride and can-do attitude–collective feelings of optimism that were wildly at odds with the Marxes, who had by this film reached something of a pinnacle in antiestablishment sentiment. The challenge of Horse Feathers‘ “whatever it is, I’m against it” is fulfilled by Groucho’s Rufus T. Firefly, leader of the mouse-that-roared country of Freedonia and so precise a despoiler of despots that Benito Mussolini banned Duck Soup because he believed it to be a direct attack. Firefly’s dedicated unwillingness to do anything his constituents require of him in favour of personal wars and arbitrary decrees and nepotistic appointments paints a grim picture of leadership, indeed. Yet it’s because of the film’s unerring satirical eye that it became the group’s biggest box office failure, swimming against the stream, as it were, of popular sanguinity. It almost sank Paramount, necessitated the Brothers’ relocation to Irving Thalberg’s MGM, and represents the last time the Marxes were allowed to be completely lawless and eternally centre-stage.

Though home to the mirror gag that Harpo would recreate on an episode of “I Love Lucy”, a peanut vendor gag that makes good use of the hat-as-castration device, and the return of Margaret Dumont after a two-film hiatus, Duck Soup is particularly memorable for a climactic battle sequence that, like the football game in Horse Feathers with big business, represents the end of the conversation in many ways, as satires go, of the madness of war and the tunnel-visioned caprice of the men who send us into conflict. Fourth-wall violations, a disconcertingly-animated tattoo (following a strange existential sequence where tattoos provide textual information), and a dizzying succession of edit-break costume changes mark Duck Soup as a little surreal, a little avant-garde (a little Memento, a little The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover) and especially courageous in testing the envelope of the cinematic medium. Yet what is most commonly described as a film without a narrative reveals itself to have a thematic throughline that’s ironclad and irreducible: Duck Soup is a piece of absolute, stunning cynicism, that rare artifact that plays better the darker the social and political climate. Seventy years later, it’s current again.

THE DVDs

Wresting the Paramount titles away from Image Entertainment, Universal appears to have recycled the company’s transfer of The Cocoanuts for “The Marx Brothers Silver Screen Collection”, which means that either it was as good as it gets or that every telecine operator on the planet was busy for the few hours it took to port the flick over from a disc released at the dawn of the format. Scratchy, garbled, visually noisy, The Cocoanuts looks just awful on DVD, at one point jittering in a manner that replicates the experience of watching a decomposed 16mm print in somebody’s basement. The DD 2.0 mono audio is an upgrade from its Image predecessor, if only in volume: the hisses and pops are rendered with breathtaking fidelity. There are no special features specific to this platter.

Animal Crackers is a truer beginning for the Marx Brothers’ cinematic canon than The Cocoanuts, thematically speaking, but technically it still feels mired in the look and pacing of the stage. It wouldn’t be until their next film, Monkey Business, that the Marx shtick at last found its home as an animal of the screen instead of an orphan of the stage. The second disc in Universal’s “The Marx Brothers Silver Screen Collection,” Animal Crackers is in relatively good shape compared to The Cocoanuts, no thanks to any effort on the part of the studio. Rumours of Paramount dumping third-party dupes once their Marx Bros. titles became MCA property in the ’40s would partially account for the films looking so lousy now, but it doesn’t explain why the previous DVD incarnations from Image Entertainment have just been recycled. Technological advances in the intervening years, I protest in complete ignorance, surely warranted remasters–if not, perhaps this box set needed to wait until they did. Although the Dolby 2.0 mono sound, like the video, is an improvement over that of The Cocoanuts as well, it’s really no great shakes.

Monkey Business, found on the third platter of “The Marx Brothers Silver Screen Collection”, is not only the best film so far, but also the film in the best condition. The print is without significant grain or defect and the Academy ratio transfer is vibrant and fresh, with every straw of hay in a late-film barnyard scuffle (an alternate ending filmed after the original closer was scrapped due to Depression-era financial jitters, as it required that a brewery set be built in order to maintain continuity) distinct. Again, the Dolby 2.0 audio mix is sufficient, if victim to the kinds of pops, tinniness, and fizzles of a soundtrack of this age. Special features specific to this film/disc are non-existent.

Lamentably, this fourth disc in “The Marx Brothers Silver Screen Collection” backslides in terms of visual transfer, notably during a hotel-room exchange–the result of what appears to be an entire reel of damaged footage. Splices are jarring, picture quality is horrific, and a sigh goes up in hopes that a better negative of this film is someday discovered in some closet of a Scandinavian mental institution. The DD 2.0 mono mix delivers the dialogue in a predictably tinny–if always clear–manner, with a nice legibility even though much of the talking is breathlessly rat-tat-tat. An interesting, long-form trailer, the first disc-specific extra so far, rounds out the presentation.

With a nice, clear print to work from, Universal’s video transfer of Duck Soup is probably the clearest of the five films compiled in their Silver Screen Collection, but also not much of an improvement over my old VHS copy. Some lines (most distracting during the aforementioned mirror bit) and snowy grain that I’m reasonably certain could have been eliminated with a little technological elbow grease mar the picture in a distinctly VHS manner. I wonder if the slackness of this presentation suggests a more careful treatment somewhere down the road in the same way that I wonder if Ace in the Hole will ever be released on DVD. (In other words, not holding my breath.) The DD 2.0 mono audio is a little more spacious, but similarly indistinguishable from previous home video mixes. An amusingly chaotic (and nicely restored, oddly enough) trailer that ends with the “MCA Videocassette Inc.” logo–thus betraying its source–is the only film-specific special feature.

A sixth disc housing non-specific special features, coupled with a pretty poor insert booklet that provides chapter listings for each disc along with the barest of bare-bones write-ups on the films themselves, represents the only extra goodies in “The Marx Brothers Silver Screen Collection”. Therein, find three brief “Today Show” interviews with Harpo (1961, 7 mins.), Groucho (1963, 5 mins.), and Harpo’s son, William (1985, 5 mins.). Harpo is there to stump his autobiography and cuts up (mutely) while the hosts smoke and chortle in the unbecoming way of talent-less Regis manqués when confronted with marginal Robin Williams-esque performers who don’t know when their shtick is getting tired. Groucho, looking appropriately crotchety and put-out, talks over the talking heads, flirts with the girl in a pretty shocking way, and sets up his duck-walk for long enough that anything he does becomes anti-climactic. William’s appearance with Gene Shalit is arguably the most interesting, as the Marx offspring brings along some home movies. A shame that so much of this brief segment is taken over by a clip from Duck Soup and Shalit’s own fossilized introduction. For artists of the Marx Brothers’ importance, for these to be the only extras in a box set commemorating their most fulsome period is something like a surrender to the elements of venality and stupidity against which the troupe throughout their joint careers. A bad taste in the mouth, for sure: don’t be fooled by the pretty packaging.

- The Cocoanuts

96 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English SDH, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Universal - Animal Crackers

97 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English SDH, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Universal

- Monkey Business

77 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English SDH, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Universal

- Horse Feathers

68 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English SDH, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Universal

- Duck Soup

68 minutes; NR; 1.33:1; English DD 2.0 (Mono); English SDH, French, Spanish subtitles; DVD-5; Region One; Universal

![Dirty Harry [Ultimate Collector's Edition] - Blu-ray Disc FFC Must-Own](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/6a0168ea36d6b2970c016304cd768d970d-600wi.gif?resize=100%2C91&ssl=1)

![Wolf Creek (2005) [Widescreen Edition - Unrated Version] - DVD + Hostel (2006) [Unrated Widescreen Cut] - DVD|[Director's Cut] - Blu-ray Disc wolfcreek](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2007/10/wolfcreek.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)