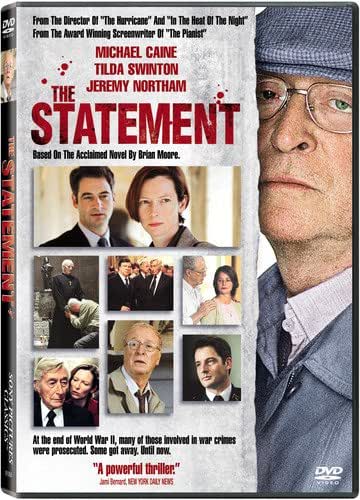

½*/**** Image A Sound A Extras C

starring Michael Caine, Tilda Swinton, Jeremy Northam, Alan Bates

screenplay by Ronald Harwood, based on the novel by Brian Moore

directed by Norman Jewison

by Walter Chaw A so-so director even at his best (thinking of The Cincinnati Kid) who vacillates aimlessly between soft romantic comedies and undisguised, under-informed diatribes against barn sides like big business (Rollerball, F.I.S.T., Other People's Money), American racism (In the Heat of the Night, A Soldier's Story, The Hurricane), and religious intolerance (Jesus Christ Superstar, Agnes of God, The Statement), Norman Jewison is full of activism–just not terribly ripe with ideas and perspective. His fists are of ham and his pulpit is splintered from the hammering, Jewison's political films distinctive mainly for the broadness of their focus and his romantic films distinctive for the extent to which the facile cultural stereotypes he seems so concerned about elsewhere are machined into the rom-com grist mill therein.

|

Confused at its core and too befuddled to make that a virtue, Jewison's The Statement tackles the Holocaust and Vichy France's complicity in it in a thriller of manners that compares the modern-day Catholic Church to Nazi Germany, hiding as it does war criminal Pierre Broussard (Michael Caine) in various abbeys scattered around France while providing him a share of the tithe to support his continued fugitive status. It's a reprehensible film in its blanket condemnation of Catholicism–and reprehensive, too, in its attempt to gain some footing for its low-grade thriller schmaltz on the horned backs of genocide and a certain corpulent anti-French viewpoint (represented by a fat French official more interested in his fish stew than prosecuting neo-Goebbels), as well as, of course, in Jewison's choice of an all-British cast to portray a France where not one person seems to speak French.

On the trail of Broussard is a team of laconic assassins hired by some shady Jewish victims' advocacy group or something (based in Canada, natch, because the good guys in Jewison's world are generally Canadian), in addition to a team comprised of a half-Jewish judge Annemarie (Tilda Swinton) and gendarmerie colonel Roux (Jeremy Northam) that wants to bring Broussard to a more civilized form of justice. The Broussard tug-of-war reaches all the way to the top (John Neville), it seems, implicating all of the current French government and Catholic Church in a conspiracy to keep war criminals living comfortably in the cafés and chalets of Gaul. Broussard himself, in the meantime, traffics in a jittery piety punctuated now and again by a preternatural ability to murderously evade capture and be mean to his estranged wife's (Charlotte Rampling) dog.

As the hissable Broussard, Caine is brilliant, but his anachronistic accent here, as in The Cider House Rules, reduces his performance to obviously distracting, attention-drawing work that feels wholly out of place in a film that boasts as its chief descriptive metaphor a watched pot. The picture doesn't have a point of view except a blaring, meaningless "Liberal" sign tattooed across its proverbial forehead, the kind of politicism taught on bumper stickers and "Mean People Suck" T-shirts that takes an unassailable position (corruption bad, Holocaust also bad) and attaches it to ambiguous issues (Nazi sympathy, redemption, justice) in the knowledge that for many, it'll stick. But it's not an argument: The Pianist screenwriter Ronald Harwood, working from a novel by Brian Moore, demonstrates again that without a Polanski to give his simplistic ideas structure and depth, he writes one-dimensional scripts (Taking Sides, the remake of Cry, the Beloved Country) that dance with hysteria. The Statement is awful–not just scatterbrained but boring in the burnished way that films believing themselves to be more literary than they are (see: the Anthony Minghella canon) tend to be.

THE DVD

Universal shepherds The Statement to DVD in a presentation packed with extras–the same sort of processional pomp and circumstance with which Jewison ends his picture, as it happens, revealing of the double-edged sword of using end-titles in any film, much less one with such a loaded topic as this. The 1.85:1 anamorphic video transfer is lovely, portraying the French countryside in varying shades of earthen, Renoir yellows and browns. Indeed, much of the picture was shot in Marseilles, but alas the humanism of Renoir is lost here underneath a smothering shroud of crap. Edge-enhancement, grain–all the maladies of the DVD experience–are in minimal evidence here as separation is sharp, flesh tones a little pale but probably by design, and landscapes, as mentioned, look vibrant. The audio, mixed in 5.1 Dolby Digital, largely wastes the six-channel environment, with most of the sound information emanating from the front mains. (Given the tenor of the flick, one could reasonably expect the soundtrack to be isolated to the far left.) It is, however, clear and more than adequate for the picture's needs.

Jewison weighs in with a film-length yakker that is migraine-inducing in its self-congratulation and inanity. He recites plot with the kind of intimate fervour reserved for someone telling you what he thinks are great secrets, they being in this instance that the French government collaborated with Nazi Germany during WWII, that the audience is surprised to find out that the Broussard character is a killer (shouldn't we be the judges of our own surprise?), and that the wizened director doesn't seem to understand the difference between the terms "laying the groundwork" and "laying the pipe." I also learned that every single actor in this picture is "celebrated" and not French. Jewison's closing rejoinder, a gently chiding, "Thanks for including this film in your library, and films are indeed the literature of this generation," is the problem of the picture in a nutshell: he's encapsulated an observation in a patronizing bon mot–but nobody's arguing with him, nobody needs the lesson, and, ultimately, nobody's probably still listening except those of us obliged.

The disc continues with junket interviews featuring Caine and Jewison (7 and 9 mins., respectively), which, if you know anything about junket interviews, are completely unhelpful and extraordinarily irritating. Meanwhile, the 11-minute "Making of" featurette is typical enough to serve as a prototype for such things. A block of deleted scenes (one an extended intro of the second assassin, the other a meandering chat between Annemarie and Roux) runs about 6 mins. and intrigues mainly in that it would have made not one bit of difference were either included in the film. Alas, there's no commentary to justify what it was about these scenes that so doomed them to the special features section; Jewison does mention at a couple of points during his yak-track that he hopes to preserve some missing footage, but from what I could tell, he's not referring to the abovementioned elisions. A theatrical trailer that again undermines Jewison's assertion that we're surprised by Broussard's gunplay rounds out the platter. Originally published: May 11, 2004.

![The Cincinnati Kid (1965); The Thomas Crown Affair (1968); Junior Bonner (1972) [Western Legends] - DVDs The Cincinnati Kid (1965); The Thomas Crown Affair (1968); Junior Bonner (1972) [Western Legends] - DVDs](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/plugins/contextual-related-posts/default.png?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)

![Rollerball (2002) [Special Edition] - DVD Rollerball (2002) [Special Edition] - DVD](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2002/06/183995884_80_80-9592123.jpg?resize=80%2C80&ssl=1)

![Fiddler on the Roof (1971) [2-Disc Collector's Edition] - DVD fiddlerontheroof](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2007/01/fiddlerontheroof.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)