*½/**** Image A Sound A+ Extras B

starring Mike Myers, Beyoncé Knowles, Michael York, Michael Caine

screenplay by Mike Myers & Michael McCullers

directed by Jay Roach

by Walter Chaw In the grand tradition of Final Chapter – Walking Tall, the third film in the Austin Powers franchise, Austin Powers in Goldmember, begins and ends with our hero watching himself being portrayed by someone else in a movie of his life–a level of post-modern reflexivity that is taken to such grotesque heights by the film that what emerges is actually fascinating in a detached, unpleasant, deeply unfunny sort of way. Mike Myers’s obsession with body distortion and cannibalistic consumption and auto-consumption likewise reaches a macabre pinnacle in the picture’s best running gag–the preoccupation with Fred Savage’s mole with a mole–and with a new circus geek for the Myers pantheon (joining blue-eyed bald albino Dr. Evil and Shrekian Scot Fat Bastard), the Dutch villain Goldmember, who makes it a habit to eat giant flakes of his own skin. We meet Goldmember (so named for his prosthetic bullion bar and ingots) in another bit of multi-layered absurdity during a time-travel journey to New York circa 1975 and the fictional Studio 69, with Myers referencing his own most critically praised performance as Studio 54’s perverse Steve Rubell. A study of Myers’s Dick Tracy-like mania with latex appliances would no doubt fill volumes.

Goldmember is perhaps the most horrific deconstruction of the self and the mortification of corporeal identity since Bergman’s Persona. Star cameos from Tom Cruise, Gwyneth Paltrow, Danny DeVito, Kevin Spacey, Steven Spielberg, Ozzy Osbourne, Quincy Jones, and, most disturbingly, Britney Spears (as first a Fembot and then as herself, propositioning Verne Troyer during the closing credits) dominate the proceedings. These cameos are played with a kind of hostile frankness that elicits the most uncomfortable kind of laughter; here are actors spoofing themselves and their milieu in a film that spoofs the spy spoofs of the Seventies, which themselves chose as their target films (the James Bond series, in particular) that had tongue already planted firmly in cheek.

The picture–an extended treatise on the vertiginous emptiness of this kind of film and a truly disquieting glimpse into the mind of Mike Myers–presents us with an infinite series of circular in-references. Myers’s personality, it seems, is unmoored from personal identity and fascinated with ingestion, procreation, and irregularities of the flesh. Expanded too far, Goldmember begins to touch upon unanswerable existential conundrums involving the unnaturalness of created beings involved themselves in the alchemy of creation–machines making machines and, more to the point, formulas mixing formulas.

Less esoterically, Goldmember, save Savage’s mole (and a bit stolen gag for gag from the second Austin Powers film), is a boring and enervated comedy that limps around reeking of the pathetic and the desperate urge to be loved long after the passion for the thing has waned. The first film worked in its limited way because it transplanted a spy spoof protagonist from an In Like Flynn-style movie into the present day: the anachronisms were groovy, baby, even though fish-out-of-water scenarios are almost as tired a formula as submarine operas. Ever since, however, the Austin Powers films have forgotten that there need to be foils and straight men in this type of comedy–without them, what you’ve created is a fish-in-water scenario, a perverse alternate universe that loses its novelty without anything recognizably human to provide commentary and comparison. Goldmember is the chocolate factory without Charlie.

Michael Caine appears as Austin’s father, Nigel. In the first of several key plot points introduced and completely forgotten, he misses Austin’s knighting ceremony, the trauma of which leads to a flashback to 1958, where we learn that Nigel also missed Austin’s “International Man of Mystery” award ceremony at prep school. What we want to know is where Nigel was during those key moments and why, if Austin had the benefit of thirty years frozen, does Nigel appear to be no more than twenty years older than Austin: Was Nigel also frozen? And if not, why is there a 1940-ish clip of Michael Caine cribbed from a film circa 1975? It could be–hell, it is–sloppy filmmaking, but again, the forced artificiality of Goldmember demands a different reading of these errors. With most of the dialogue either badly timed riffs on familiar catchphrases, enthrallingly bald product placements, or florid euphemisms for a man’s package, Goldmember doesn’t give more serious examinations much help.

Pop princess Beyoncé Knowles struts around in a mean Pam Grier mien long on boredom and short on sass as Austin’s new partner Foxxy Cleopatra, while Verne Troyer is again treated like some kind of child or pet. Even if the intention of Goldmember was to comment satirically on our culture’s unkind propensity to treat little people like children or animals, the resultant effect is far less the magnificently sad indicting laughter of Shallow Hal than the feckless laughter of turn-of-another-century audiences enticed into a sideshow tent by a barker’s (read: publicity department’s) hyperbolic promises.

Goldmember is a genuinely interesting failure of a film. It plays like a cry for help, though from an individual or an industry, I’m not entirely sure. A pitch-black movie of uncertain intent that never for a moment acknowledges its heart of darkness, it buries its cynicism under peculiar musical interludes (at least five), recycled pratfalls, and comedy tepid and uninspired enough to demand a very careful handling. On an essential level, Austin Powers in Goldmember seems to understand that it’s a slippery beast composed of a vast series of convoluted loops of signs and signifiers: a Japanese man named “Mr. Roboto” whose subtitles are visible and misread; a fight scene ended when a “wire-fu” wire snaps; and, in a canny moment, a scene where Dr. Evil as Hannibal Lecter accidentally frees himself from a high-tech containment unit. Almost more than any other, this joke encapsulates the picture, eliciting a notably queasy chuckle (aren’t we, after all, the butts of this kind of joking) that comments upon the wide audience’s voyeuristic hunger for cruel mayhem. Aside from the hermeneutical possibilities of the piece, Goldmember exists as an almost complete failure of its most basic precept and supposed reason for being: to make one laugh. Originally published: July 26, 2002.

THE DVD

by Bill Chambers I’m not here to provide revisionist opinion, but I liked Austin Powers in Goldmember more than Walter did and would even go so far as to call it the best of the trilogy; the perfunctory nature of the film seems to liberate it from doing anything other than the thing the franchise does well, which is a kind of funny-accent theatre. Holes abound, Austin’s mojo is even more AWOL than it was in the last film, and Mike Myers definitely has issues that, like Eddie Murphy, he works out through layers of prosthetic make-up, but it has more jokes per capita (delivered at a faster pace) than either the original film or The Spy Who Shagged Me.

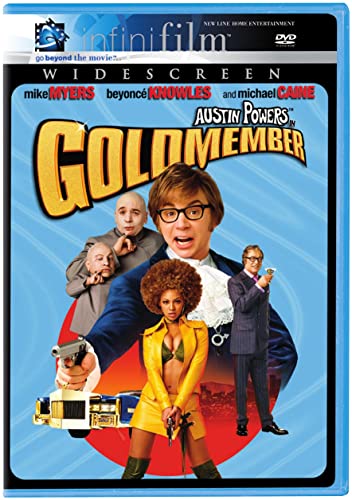

Austin Powers in Goldmember arrives on DVD in separate widescreen and fullscreen editions. We received the former, on which the film appears in a 2.35:1 transfer enhanced for 16×9 displays. The picture is crystal clear and the colours have a controlled intensity that’s quite appealing. Shadow detail doesn’t get any better; in short, this is as good as if not better than The Spy Who Shagged Me in terms of video quality. The audio, on the other hand, is something I wasn’t prepared for: The DTS-ES 6.1 and DD EX-encoded 5.1 tracks come close in impact to the just-released “Extended Edition” of The Fellowship of the Ring. The mix itself isn’t exceptionally clever, but the surround channels and subwoofer are in almost constant employ–it’s time to upgrade your gear if you’re not fully persuaded by the club ambience in the Studio69 sequence. Less exciting is the somewhat disengaged screen-specific yak-track from director Jay Roach and Myers, returning to the hot seat after sitting out the first sequel’s DVD commentary. As a fellow Torontonian, I was disappointed that Myers pointed out several of the film’s Canadiana references whilst failing to mention that Studio69, satiric of Studio54 though its name may be, is an actual nightspot in downtown Toronto.

Extras on this “infinifilm” disc (haven’t seen one of those in a while) from New Line are fan-friendly but not very instructive. The “Beyond the Movie” section (which, if you watched the film with the infinifilm feature activated and clicked whenever prompted, has nothing additional to offer) includes four featurettes. In “MI-6: International Men of Mystery” (4 mins.), spy-ographer Ernest Volkman discusses James Bond’s and Austin Powers’s real-life antecedents; Myers explains how cockney slang works in “English, English” (2 mins.); “Disco Fever” (4 mins.) provides an overview of the music and clothing choices for the Studio69 derby; and “Fashion vs. Fiction” (2 mins.) sees costume designer Deena Appel, hairstylist Candy Walken, and production designer Rusty Smith defending instances of artistic license. Turning on the “Fact Track” under Beyond the Movie yields some interesting pop-up trivia, such as Seth Green’s role in the christening of Jodie Foster’s production company, as well as the difference between nuclear fission and fusion.

The “infinifilm: all access pass” contains the subheading “The World of Austin Powers.” There you’ll find a 6-minute exploration of the improvisational techniques the filmmakers employed (“Jay Roach & Mike Myers: Creative Convergence”); a series of segments (“Confluence of Characters”) that delve a little deeper (but not much) into the inception and execution of Goldmember, Foxxy Cleopatra, Nigel Powers, and the teenaged incarnations of Evil and Austin (played by a pair of affable interview subjects, Josh Zuckerman and Aaron Himmelstein, respectively); a brief behind-the-scenes look at the “Opening Stunts” (2 mins.); a closer inspection of “The Cars of Austin Powers” (2 mins.); and an “Anatomy of Three Scenes”–the gates of New Line Cinema dance number, the aforementioned disco roller-boogie, and the sumo battle, each a montage of set footage with non-optional commentary by Roach; a 4-minute introduction to the film’s more-than-meets-the-eye “Visual FX,” hosted by effects supervisor Dave Johnson; and a breakdown of the 8-second F/X shot in which Goldmember escapes into Evil’s submarine lair.

Your all-access pass dries up with four music videos (for Beyoncé‘s “Work It Out,” Britney Spears‘s “Boys,” Ming Tea‘s novelty song “Daddy Wasn’t There,” and Dr. Evil & Mini-Me‘s gangsta take on “Hard Knock Life”), four teaser trailers and one theatrical, all in 5.1, and best of all, fourteen deleted scenes totalling twenty-two minutes, presented in spit-polished anamorphic widescreen with a choice of soundtracks (DD 5.1, 2.0 Dolby Surround, or Roach commentary). Roach explains that most of these were cut for pace; I’m sad to see go, as is he, a Magnolia parody wherein Rob Lowe’s No. 2 resurfaces. Alas, the abandoned cameos by Heather Graham and Elizabeth Hurley are nowhere to be found, but the puerile sight of Mini-Me literally chewing his way through a prisoner’s chest cavity surely compensates. DVD-ROM owners can choose from a selection of twelve scenes from the film to redub (I imagine it’s fun in groups) and visit weblinks. The attractive blue keepcase of this so-so SE does make it more enticing.

95 minutes; PG-13; 2.35:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1 EX, English DTS-ES 6.1; CC; English subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; New Line

![15 Minutes (2001) [Infinifilm] - DVD 15 Minutes (2001) [Infinifilm] - DVD](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2001/08/103890076_80_80-7315196.jpg?resize=80%2C80&ssl=1)

![Rush Hour 2 (2002) [infinifilm] - DVD Rush Hour 2 (2002) [infinifilm] - DVD](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/plugins/contextual-related-posts/default.png?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)