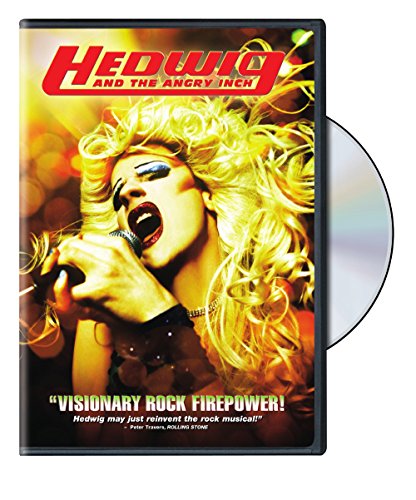

***/**** Image B Sound A Extras A+

starring John Cameron Mitchell, Michael Pitt, Miriam Shor, Stephen Trask

screenplay by John Cameron Mitchell, based on his play with Stephen Trask

directed by John Cameron Mitchell

by Walter Chaw A pretension-laden, soul-dissection opera crossed with the brooding musical chops that Pink Floyd all but defined in the late-Seventies, John Cameron Mitchell's Hedwig and the Angry Inch is Velvet Goldmine and All that Jazz by way of Pink Floyd The Wall–a bombastically endearing romp that is as infectious as it is (surprisingly) poignant. The anchor for the film is Mitchell's incendiary turn as the titular Hedwig, a transsexual/transvestite, Eastern Bloc rock diva on a national tour booked into Bilgewaters family restaurants in the same cities as flavour-of-the-month pop superstar Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt). Hedwig believes that Gnosis has stolen his songs from him, yet we sense the real theft was that of trust and the promise of love. Early on, we're shown a fantastically-conceived bleach-bypass/animation/performance piece set to a very nice Plato's Symposium-inspired tune ("The Origin of Love") that offers an explanation of the absent feeling that impels us all to find succour in a mate, a friend, or art. Hedwig and the Angry Inch never gets as good as this again, but it's almost impossible to imagine how it could: the sequence, lasting all of ten minutes, is one of the highlights of the year in cinema.

The story unfolds to the tune of extraordinarily well-conceived musical numbers (born of hundreds and thousands of live performances) that detail Hedwig's Spartan upbringing behind the Berlin Wall. From the start, we understand that he equates himself with that national divide ("Don't you know me? I'm the new Berlin Wall! Try to tear me down!"), and as the film progresses, we see how Hedwig worries over the ways in which he has been breached, martyred for love and beauty, and otherwise violated–an ironic Christ blurring the lines between reality and expectation and gender. The opening image of Hedwig as he throws out his arms in emulation of crucifixion speaks more deeply at the end of the film than it does at the beginning, a truth that clarifies how carefully-plotted Hedwig and the Angry Inch really is.

Mitchell details Hedwig's homosexual awakening, culminating in a botched sex-change operation that leaves him mutilated with an "angry inch," his flight from East Berlin by the good graces of a cad of an American G.I., Luther (Maurice Dean Wint), and his grassroots tour stalking his one-time lover Tommy Gnosis. The film is defined by its soundtrack as well as by a striking editing job courtesy of Andrew Marcus (American Psycho) that handily counteracts first-timer Mitchell's relatively flat and uninspired direction. It's a sprawling, episodic, ambitious movie that at any moment threatens to collapse under its own elaborate structure and aspiration but is buoyed at every turn by Mitchell's confidence and raw instincts as a performer.

The triumph of Hedwig and the Angry Inch is in its diagramming of loneliness and identity, people orbiting one another out of mutual need and complementary lacks. Most importantly, Mitchell charts the manifestation of art and personal expression in that melancholy. Evolving from a drag act into a long-running off-off-Broadway show that was conceptualized and performed by Mitchell and composer/lyricist Stephen Trask (the two met over a Fassbinder biography), Hedwig and the Angry Inch is involving, insightful, and, despite its outlandish camp trappings, utterly human. Overall a strong debut, the film does flag in its second half, especially in parts involving Pitt's Tommy Gnosis, who's every bit the underwritten gay caricature Hedwig is not. Still, Hedwig is a reclamation of rock and roll as a means towards self-discovery, impressive for the way its honesty touches across a wide demographic (unlike cult exercises like The Rocky Horror Picture Show, against which Hedwig is most often compared) and vital for the way it honours the idea that music can be a collective confessional odyssey. Beyond its archetypal smarts, however, Hedwig and the Angry Inch is a tremendously fun rock melodrama. For its combination of story, execution, and music, it's perhaps the best of its kind.

THE DVDNew Line's Platinum Series DVD of Hedwig and the Angry Inch presents the film in a 1.85:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer that looks smashing considering the film's lo-fi origins–the bleach-bypassed flashbacks demonstrate a striking use of a limited palette. Shadow detail is decent and black levels are adequate. The DTS and Dolby 5.1 mixes are just wonderful: the dialogue is sharp and the noise atmosphere is rich and evocative, with good use of rear-channel crowd effects. The music sounds fabulous, even more so in DTS. "Hed-heads" should buy this disc for not only its video and audio presentation, but also its stunning array of special features: a feature-length commentary; an 86-minute documentary about the evolution of the Hedwig character; and a deleted scenes section with optional commentary.

Mitchell and DP Frank DeMarco's commentary is rich with anecdotes and technical information. They resist narrating the action, that pitfall of many screen-specific commentaries, instead providing edifying, soft-spoken discussion free of false humility. Mitchell is aware of his limitations and discusses them; likewise his strengths. Also tremendous is the documentary Whether You Like it or Not: The Story of Hedwig, a feature-length piece that showcases invaluable footage from the first appearance of the Hedwig character at Club Squeezebox, all the way through to performance stills of those actors (including Ally Sheedy) who have donned the Hedwig in the continuing New York production and interviews with investors and producers interested in bringing the film to the screen. Clips shot at the Sundance Film Lab (perhaps the most vital resource for independent filmmakers in the United States today) offer a fabulous glimpse inside the workshop process in the nascence of a film project, as do early screen tests, stock tests, and audition tapes. The deleted-scenes section mostly comprises one 12-minute chunk that re-inserts much of Andrea Martin's manager character moments, including a sight gag that doesn't really work and is thus thankfully only an outtake. A theatrical trailer, song-by-song menu access, and cast & crew filmographies round out a sterling presentation.

95 minutes; R; 1.85:1 (16×9-enhanced); English DD 5.1, English DTS 5.1, English Dolby Surround; CC; English subtitles; DVD-9; Region One; New Line

![Countess Dracula (1971)/The Vampire Lovers (1970) [Midnite Movies Double Feature] - DVD|The Vampire Lovers (1970) - Blu-ray Disc 6a0168ea36d6b2970c017c3811fd79970b-800wi](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/6a0168ea36d6b2970c017c3811fd79970b-800wi.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)